solidarity

I wish I could sit beside you on a cushion on the floor and have a cup of tea with you. I would like to snuggle your baby in my arms. I would like to hear your story. I know you have a sad story, and if I heard it, I would weep.

I know you are good and loving women. I’m sorry you have lost so much. I’m sorry you had to come to a country, a city, and a house that is not yours.

I can imagine you in your own country, strong women serving others. I can imagine you making beautiful food and sharing it with your family and friends. I can imagine you caring for your mothers and daughters, fathers and sons, sisters and brothers and friends. Just the way I do.

Because that’s what women do. We are compassionate. We give. We serve. We protect. We work hard to make the world better for the people we love.

Wherever I go in the world, I discover that we women are very much alike. We may have different clothes. Different languages. Different cultures. Maybe our skin is a different color. But in our hearts, we are the same.

That’s why we can look into each other’s eyes and feel connected. We can talk without using words. We can smile. We can hug. We can laugh.

And sometimes, we can feel each other’s pain. I have prayed that God would help me feel your pain. I wish I could remove your pain. I wish I could help you carry it.

SINCE HIS ELECTION as the 265th successor of St. Peter, Pope Francis has provided a refresher course on Catholic social teaching to the world’s 1.2 billion Catholics. “Catholic social teaching is no longer a secret,” says Jean Hill, director of peace and justice for the diocese of Salt Lake City. “Everything Pope Francis is saying comes from social doctrine and is about social justice.”

Through his various homilies, speeches, and meetings, Francis is “reading the signs of the times” and making practical application to the issues of the day. Some of his most powerful statements to date were made in his first pastoral document, “The Joy of the Gospel,” including this declaration: “I prefer a church which is bruised, hurting, and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a church that is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security.”

Pope Francis is calling the faithful to be more merciful, compassionate, joyful, and centered upon the needs of the poor and vulnerable. He wants a church that sees the human person before the law and one that does not “obsess” about a narrow set of issues, but affirms both human life and human dignity. He invites Catholics to pray, reflect, and embrace the beauty and breadth of Catholic social teaching—a rich tradition that is predicated on the dignity of the human person.

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) defines Catholic social teaching as “a central and essential element of our faith. Its roots are in the Hebrew prophets who announced God’s special love for the poor and called God’s people to a covenant of love and justice.” This teaching is also founded on the life and words of Jesus. It posits that “every human being is created in the image of God and redeemed by Jesus Christ, and therefore is invaluable and worthy of respect as a member of the human family.”

On Feb. 8, tens of thousands of people gathered in the North Carolina capital city, Raleigh, for what organizers called the Moral March. It was a follow-up to last year’s “Moral Monday” movement that started in April 2013 when Rev. William Barber II, president of the North Carolina NAACP, and 16 others were arrested inside the North Carolina legislature for protesting sweeping voting restrictions proposed by the Republican-controlled state government.

I ALMOST DIDN’T go to the Moral March. I kept looking for excuses. There was all that work to be done for next week. I told my professor I’d miss Friday’s preaching class. I hoped she’d chide me and I’d feel guilty enough to stay. Instead she said, “Great, go with my blessing.” I told my tutor I’d miss tutorial. She said, “I’m so glad you’re going to the march.”

Why couldn’t I go to a normal graduate school where no one left their rooms? But instead I went to seminary, and to Union, of all places!

I said, God, I’m crazy to go. Mild laughter was the only response. I glared at my reflection in the dark window. The reflection raised her eyebrow and said, don’t be left behind now.

The little voice in the window stayed with me as I put an extra pair of thick socks in my bag. Don’t be left behind, reading books about other people’s marches and other people’s spiritual revelations and other people’s religions. This march is historic, my reflection informed me. Go and be part of history. This is your history.

This is your time.

WHEN I MOVED out of my Sojourners magazine office in 1988, I took with me two signed review copies of books. One was Roll the Union On: A Pictorial History of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union. It was inscribed to me personally by H.L. Mitchell, a founder of the STFU, so I felt entitled to keep it.

The other book bore no inscription, just a simple black ink signature above the Simon & Schuster logo. It was called Carry It On! A History in Song and Picture of America’s Working Men and Women, and the co-author who signed it was Pete Seeger. I’m looking at that signature now, as I write this on the day Seeger died.

I told myself that I kept that book because I thought it might come in handy. After all, it had 11 translations of “L’Internationale” and all the words to “Solidarity Forever.” But really I kept it for the signature. I liked the idea of having something that I knew had come from the hand of someone who had ridden the rails with Woody Guthrie. Seeger was our living connection to the culture of the 1930s when, for a moment, radical dreams about a country owned and operated by its ordinary citizens seemed almost ready for prime time.

Of course, that moment passed, and those dreams were shattered by the Red Scare and the Cold War that followed. But Seeger came out on the other side with his integrity and ideals intact. Despite being honored by the last two Democratic presidents, he never renounced his radical vision of what America could be. Seeger left the Communist Party in the early 1950s and frankly acknowledged that he should have done so sooner, but he never stopped calling himself a “small c” communist. In 1994, he told The Washington Post, “Our ancestors were all socialists: You killed a deer and maybe you got the best cut, but you wouldn’t let it rot, you shared it.” Still, he was a pragmatic radical, who added that socialists should recognize that “every society has a post office and none of them is efficient. No post office anywhere invented Federal Express.”

WHEN I MOVED out of my Sojourners magazine office in 1988, I took with me two signed review copies of books. One was Roll the Union On: A Pictorial History of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union. It was inscribed to me personally by H.L. Mitchell, a founder of the STFU, so I felt entitled to keep it.

The other book bore no inscription, just a simple black ink signature above the Simon & Schuster logo. It was called Carry It On! A History in Song and Picture of America’s Working Men and Women, and the co-author who signed it was Pete Seeger. I’m looking at that signature now, as I write this on the day Seeger died.

I told myself that I kept that book because I thought it might come in handy. After all, it had 11 translations of “L’Internationale” and all the words to “Solidarity Forever.” But really I kept it for the signature. I liked the idea of having something that I knew had come from the hand of someone who had ridden the rails with Woody Guthrie. Seeger was our living connection to the culture of the 1930s when, for a moment, radical dreams about a country owned and operated by its ordinary citizens seemed almost ready for prime time.

Of course, that moment passed, and those dreams were shattered by the Red Scare and the Cold War that followed. But Seeger came out on the other side with his integrity and ideals intact. Despite being honored by the last two Democratic presidents, he never renounced his radical vision of what America could be. Seeger left the Communist Party in the early 1950s and frankly acknowledged that he should have done so sooner, but he never stopped calling himself a “small c” communist. In 1994, he told The Washington Post, “Our ancestors were all socialists: You killed a deer and maybe you got the best cut, but you wouldn’t let it rot, you shared it.” Still, he was a pragmatic radical, who added that socialists should recognize that “every society has a post office and none of them is efficient. No post office anywhere invented Federal Express.”

IN THE PRESIDENTIAL election in Honduras last November, ruling party candidate Juan Orlando Hernández was declared the winner despite serious irregularities documented by international observers. Violence and intimidation marked the campaign period, including the assassination of at least 18 candidates and activists from Libre, the new left-leaning party.

Hernández, past president of the Honduran National Congress, supported the June 2009 coup. His record of operating outside the rule of law includes bold measures to gain control over the congress, judiciary, military, and electoral authority. He helped establish a new military police force in August 2013, deploying thousands of troops to take over police functions. Hernández ran on a campaign promise to put “a soldier on every corner.”

Honduras has been named the “murder capital of the world,” with relentless violence coming from crime, drug cartels, and police corruption. Attacks on human rights defenders and opposition activists have been brutal and have allegedly involved death squads reminiscent of the 1980s. Those working to reverse poverty and injustice receive death threats, priests and lay leaders among them. They are bracing for even greater repression under Hernández’s administration.

The growing militarization of Honduran society, justified as a way of fighting crime, is fueled by U.S. support for the country’s security forces—forces reportedly involved in widespread human rights violations. By denying the repression against social movements, and congratulating the Honduran government for its supposed progress on human rights, the U.S. Embassy has made it possible for rampant impunity to continue.

IT WAS LIKE the end of the movie Lincoln. In an instant, one whole side of the House of Representatives turned, looked up at the five core fasters from the Fast for Families and erupted in overwhelmingly spirited applause. The applause reverberated throughout the chamber for what seemed like an eternity, though it was really only minutes. Ah, but what grand minutes. I wept. My body, standing there in the gallery, could not contain it.

The Fast for Families: A Call for Immigration Reform and Citizenship was launched on Nov. 12 with core fasters abstaining from all food and drinking only water. Based in a tent on the National Mall, only a few hundred yards from the Capitol building, the fast was sponsored by nearly 40 church and labor organizations and garnered support from more than 4,000 solidarity fasters across the U.S. and around the world. Our goal: To move the hearts and compassion of members of Congress to pass immigration reform with a path to citizenship.

In the Capitol building on Dec. 2, during the hour before the startling ovation, Eliseo Medina (the leader of the fast, which had reached the end of its 21st day on that Monday evening), D.J. Yoon (executive director of NAKASEC, a Korean-American advocacy agency), Cristian Avila (from Mi Familia Vota), and I received House member after member who’d come to visit us in the gallery to say “thank you for your sacrifice.” All the faces and names you usually see flashed across the screen commenting on the events of the day on cable television shows—they came to us, standing in the flesh, shaking our hands, grateful and concerned for our health.

Mary Priniski wrote in the August 2013 Sojourners magazine about churches responding in solidarity with garment workers, disproportionately women, after the terrible fires in Bangladesh’s garment factories. Now, a global church alliance has been established. Ekklesia reports:

[The alliance] provides an action plan for grassroots campaigning, and a letter for consumers to send to their retailers demanding improvements to the pay and working conditions of garment workers. Real-life stories from garment workers in Bangladesh also highlight the oppression they face and the struggle to survive.

BERNICE KING watched as, one by one, the heads of denominations from across the nation bent down to sign the Christian Churches Together in the U.S.A. “Response to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail.’” Transfixed, King—Martin King’s daughter—sat in the first row of a church one block from Kelly Ingram Park, where 50 years before children had run scared, ravaged by German shepherds and fire hoses.

As they signed, the presidents of CCT’s five church “families” stepped to the podium. Each read his or her church family’s confession of complicity with the demons of racism and injustice during and since the civil rights era.

Fifty years ago, Martin Luther King Jr. sat behind bars in the Birmingham city jail and responded to criticism from eight local white clergy’s “Call for Unity” against outside agitators. King penned prophetic words in the margins of the newspaper that carried the white clergy’s call for “law and order and common sense.”

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” King explained. He recounted the failed attempts to negotiate with city officials hell-bent on living a “monologue rather than dialogue.” He clarified: “The purpose of our direct-action program is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.”

EVERY TIME I fly into Ontario, Calif., I see neat blocks of gleaming, low-rise warehouses surrounded by well-manicured trees and shrubbery. I now know that what goes on inside those buildings is not nearly so pretty.

As a board member of People of Faith United for Worker Justice, a local faith-rooted worker justice organization, I have seen the dismal working conditions inside several of these warehouses and have heard the testimonies of workers who have been seriously injured on the job. Eighty-five percent of the warehouse workers in Southern California earn minimum wage and receive no health benefits, even though their jobs entail unloading and reloading heavy boxes.

Since many of these workers are hired through temp agencies, which are often located inside the warehouses, workers’ rights are routinely abused. When someone is injured, instead of being cared for, he or she is simply not called back to work the next day. When workers complain about poor working conditions—such as a lack of breaks, access to bathrooms, or having to lift heavy boxes into freight trucks in 108-degree temperatures—the managers tell them it’s not their responsibility because the workers are employed by the temp agency. The temp agencies in turn claim they are not responsible for conditions in the warehouses because the agencies are separate companies.

"I expect and am willing to be persecuted, imprisoned, and bound for advocating African rights. And I should deserve to be a slave myself if I shrunk from that duty or danger." -William Lloyd Garrison, Abolitionist (1805 - 1879)

With Black History Month coming up in February, many of us will remember the civil rights struggles that have brought us to where we are today. I recently read a fascinating book about that movement focused on the role of women in those efforts called Freedom’s Daughters. It highlights past generations of women activists, both black and white. They led in the struggles for abolition, desegregation, civil rights, and women’s suffrage. These movements carry with them the roots of our contemporary work for justice.

As I considered the lessons from that book I found myself resonating with many challenges, failures, and victories these women experienced, much of which was based on the race and gender dynamics of the day.

As an educated white woman who began my foray into community organizing though a summer internship in my early 20s — like many of the young women in Freedom Summer coming down from the North — I had not yet delved into the complicated nature of race relations in the United States. I started my summer feeling competent, a person who could learn and adapt to changes as I had on many previous international mission experiences. I carried with me an overly simplified belief in the romantic “beloved community.” The beloved community would come about as we worked together, prayed, and marched.

LATELY I’VE been on a campaign to read some of the classic novels that I should have read decades ago. This summer it’s been John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. There, I confessed it. All these years I’ve been coasting on repeated viewings of the John Ford film adaptation. But I’m reading the original now. And despite the hunger and hardship faced by the Joad family, I find myself experiencing nostalgia for those old hard times.

Americans fell into the Great Depression of the 1930s without the safety net of unemployment insurance, food stamps, or federally insured bank deposits. In fact, victims of the current depression have those benefits because of the things their ancestors did 80 years ago. Back then, Americans pulled together with the sure belief that we are all responsible for each other and that no one of us can, or should, stand alone. They recognized that a common plight required common action, and they gave us a trade union movement and a New Deal.

In The Grapes of Wrath, that recognition is rooted in the primary value of family solidarity, which grows to include neighbors and co-workers, and, finally, in Tom Joad’s famous speech, extends to all people struggling for justice (“whenever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat”), and even to all humanity, past and present (“maybe all men got one big soul ever’body’s a part of”).

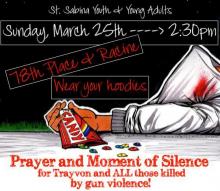

Christians and other people of good faith nationwide stood in solidarity with Trayvon Martin this weekend by wearing hooded sweartshirts — aka "hoodies"— to church.

Monday marks the one-month anniversary of Trayvon's slaying in Sanford, Florida at the hands of neighborhood "watchman" Gregory Zimmerman, who shot and killed the 17-year-old African-American boy in “self defense” for “looking suspicious” while dressed in a hooded sweatshirt.

Trayvon was unarmed, carrying only a package of Skittles, an iced tea and his cell phone.

Last week, people across the nation began wearing hoodies to work, school, and community marches in response to Trayvon's slaying and the injustice of the kind of racial profiling that it would appear directly led to it. On Sunday, many churches took that vision a step further as pastors and congregants donned hoodies and wore them to church for what some congregations called "Hoodie Sunday."

After vandals threw a 20-pound rock through the window of an Iraqi restaurant in Lowell, Mass., its owners, overwhelmed with fear at this unwarranted hate crime, came close to shutting its doors permanently.

That is, until a group of U.S. veterans flooded into the restaurant to support the owners.

Last week, Veterans for Peace organized war veterans and citizens to gather in solidarity with the Iraqi store owners. Their efforts filled the seats of the restaurant twice, and also brought the neighborhood a clear sign that city hate crimes won't be tolerated by people of good will.

Thanksgiving Day is a civil holiday, but it is a day of religious significance when we consider the ethics of commensality, the holiness of the table meal, the physical and spiritual importance of sharing a meal with family, friends or even with strangers. We share food, time, and lively conversation. We make memories. Such occasions are a part of the joy of life. When we consider the meaning of the communion elements as not only the body and the blood of Jesus, but as elements that signify the sustenance and the joy of life, then such occasions as Thanksgiving Day are joyful days that make life worth living.

Some people who work for Target, a major national retailer that plans to open its doors for Black Friday starting at midnight following Thanksgiving, have circulated a petition in protest. They are right to say enough. I stand in solidarity with them.

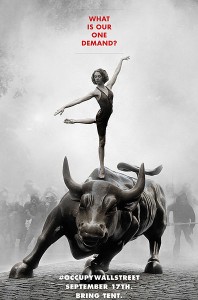

Earlirer this week, the latest of these online Occupy groups -- OccupyMusicians.com -- launched a press release, declaring solidarity with the 99 percent as a community of musicians, stretching across a wide scope of genres and fan bases. Daily, collective support of the movement is growing.

I always notice something when speaking to a mostly secular audience. Many people have been so hurt or rejected by the bad religion in which they were raised or have encountered elsewhere over the course of their lives, and, quite understandably, they are skeptical and wary of the faith community. But when someone looks like a faith leader (this is where the ecclesial robe helps ) and says things that are different from what they expect or are used to, their response is one of gratitude and the moment becomes an opportunity for healing.

After I spoke Sunday and joined the circle around the White House, person after person came up to me to express their thanks or simply to talk.

My favorite comment of the day came from a woman who quietly whispered in my ear, "You make me almost want to be a Christian."

Social justice index: USA No. 27 of 31. Democrats in Congress attempt to eat on $4.50 a day to protest potential budget cuts. Republicans shift focus from jobs to God. OpEd: Obama, the G20 and the 99 percent. In Congress, the rich get richer. The Shadow Superpower. And the U.S. sues South Carolina over immigration law.

We've compiled a list of links where you can learn more about the genesis of the #OccupyWallStreet movement, including links to news reports, organizations involved in formenting the movement and local groups in every state where you can get involved close to home (if you don't live in Lower Manhattan.)

From the official statement by #OccupyWallStreet: "As one people, united, we acknowledge the reality: that the future of the human race requires the cooperation of its members; that our system must protect our rights, and upon corruption of that system, it is up to the individuals to protect their own rights, and those of their neighbors; that a democratic government derives its just power from the people, but corporations do not seek consent to extract wealth from the people and the Earth; and that no true democracy is attainable when the process is determined by economic power."

As the tenth anniversary of 9/11 approaches, many of us are wondering how best to honor the many victims of that tragedy and its aftermath.

Here in Cincinnati, my wife Marty's answer is inviting some of our friends to join us on a walk with some Muslim and Jewish families she invited by simply calling their congregations. She got the idea from my friends and me at Abraham's Path, who are sponsoring www.911walks.org to help people find or pull together their own 9/11 Walks all over the USA and around the world. The goal of these walks is simple: to help people honor all the victims of 9/11 by walking and talking kindly with neighbors and strangers, in celebration of our common humanity and in defiance of fear, misunderstanding, and hatred.