retreat

SOLITUDE OFTEN CAN be dismissed as a spiritual luxury or afterthought. But as I’ve grown in ministry and activism, I have become convinced that solitude is a spiritual necessity.

I found myself spiritually depleted this past summer, carrying the weight of dismay and uncertainty associated with the election, anxiety and stress tied to the responsibilities of leading Sojourners in this season, and so much more. I debated whether to take some of my sabbatical. (Sojourners employees receive a one-month sabbatical after every seven years of employment.) My soul desperately needed it, but I kept pushing it off due to the tyranny of the urgent. I finally committed to a plan for August.

I’m beyond grateful for a vacation with my family, followed by a five-day silent retreat at Prince of Peace Abbey, a Benedictine monastery north of San Diego. My soul needed this spiritual reset.

Here, nobody stands

for the national anthem.

There’s no debate about

universal healthcare,

no talk of bigger border

walls or who will pay.

Here no one snapchats,

sends selfies or sexts. Google

steals no one’s idle hours.

No political parties here,

no signs to say white

lives matter too: everyone

gets it here. There’s no

NRA, no second amendment,

no bumper-sticker zealots

declaring “if you can read

this you’re in range.”

No,

here at the Pilgrim Home,

just across from the summer

play of a city pool, it’s all

cut-granite reverence

for beloved son, daughter,

dearest husband, moeder,

madre. On this level

expanse no fences

separate black and white,

they enclose. In this green

space the Mexican lies down

with the Dutch, and under

fresh rectangles the refugee

rests with the rich.

Here,

old, sleepy spruces cast

long layers of shadow

among the graves. Lilies

and orchids and roses revere

each silent name and date

and the brief dash between—

briefer than an evening walk,

than a child’s splash.

I’M PRIVILEGED to be part of a program called the Prime Movers Fellowship, a circle of mainly younger-generation social change agents launched by Ambassador Swanee Hunt and her late husband, Charles Ansbacher. In December, the Prime Movers had a retreat with the Council of Elders, an inspiring group of civil rights era activists. Those two days contained some of the most profound conversations I’ve been part of in 10 years.

Rev. Joyce Johnson facilitated masterfully, opening sessions with prayer and sacred song. Rev. John Fife spoke about launching the Sanctuary movement through churches. Rabbi Art Waskow connected the theme of the Eric Garner killing (“I can’t breathe”) with the climate challenge (“We can’t breathe”).

Rev. Nelson Johnson of the Beloved Community Center told a story about driving into the North Carolina mountains to try to convince a white supremacist to cancel a Ku Klux Klan rally in Greensboro. “I was driving alone,” he explained, “and halfway up the mountain I started to get a little scared. So I stopped my car and got down on my knees to pray. I felt God tell me I was doing something necessary, and I felt my courage return.” He got back into his car and drove on to the meeting.

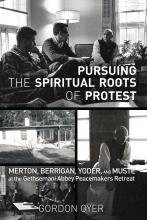

IN NOVEMBER 1964, as the long Cold War heated up again, this time in Vietnam, Trappist monk Thomas Merton set forth a koan to 14 peacemakers: “By what right do Christians protest?” For three days, these activists and theologians—famously uniting Catholic and Protestant faith traditions—met with Merton in the Kentucky hills, grappling with how and why Christians should resist the violence of war.

Historian Gordon Oyer has re-created this meeting so pivotal to the peace movement and—most important—assessed its meaning for our time. The historic retreat is meticulously sourced with detailed textual analysis of the presenters at the retreat and the writers who influenced them. Particularly impressive is the lucid summary of the era and the delicacy and respect with which the author treats cultural and doctrinal differences among the participants.

Ecumenism in peace work is thankfully common today, but in the early ’60s the blending of faith traditions at the retreat was groundbreaking. Even more revolutionary were the two Masses the group celebrated together, with Jesuit priest Dan Berrigan presiding, everyone in the group receiving communion, and John Howard Yoder, a Mennonite theologian, preaching at the second liturgy. (Both practices were proscribed at the time.)

Attendees included Phil Berrigan, later one of the creators of the Plowshares actions for nuclear disarmament, and A.J. Muste, dean of the U.S. peace movement at the time, with years of experience in War Resisters League, the Committee for Nonviolent Action, and the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). FOR’s Paul Peachey and John Heidbrink were instrumental in initiating and organizing the retreat, although neither of them could attend in the end. (Neither could two other invitees—Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King Jr.)

I DON'T WANT to keep harping about this climate change thing, but someone has to have the singular courage to stand up for the future of our globe. Someone, I mean, besides 98 percent of the world's climate scientists, the governments of every other industrialized nation, and millions of people around the world. Not counting those, I am that man.

Because I have seen the future of a warming planet, and it's not just fraught with melting glaciers and rising oceans. It's also got stink bugs.

Twice a year, Sojourners' editors and its highly esteemed art director drive to a cabin in the mountains of West Virginia to plan future issues. (I will pause briefly for Colorado readers to stop laughing convulsively at the suggestion that hilltops a few hundred feet above sea level can be called "mountains." But if I get carsick on the drive up, I'm calling it a mountain.)

After we arrived this fall—and my stomach finally calmed down—we settled into our usual method of magazine planning: a rapid-fire brainstorming of ideas both provocative and ground-breaking, but not so much that it keeps me awake. Then came the first telltale tapping sounds from the window.

A half-dozen stink bugs had gathered on the inside of the pane, with a dozen more on the outside, all of them repeatedly bumping into the window, unable to decide on one plan of action. But enough about Mitt Romney.

BIG SUR, Calif. — Perched atop the rugged splendor of the California coast south of Monterey, the Esalen Institute is the mother church for people who call themselves “spiritual but not religious." Over the last five decades, hundreds of thousands of seekers have come to this incubator of East-meets-West spirituality looking for new ways to bring together body, mind, psyche and soul.

But on May 30, as this iconic hot springs spa and retreat center celebrates its 50th birthday, a bitter dispute has broken out over its future. Like the many “seminarians” who come here after losing a spouse or a job, Esalen now faces its own midlife crisis.