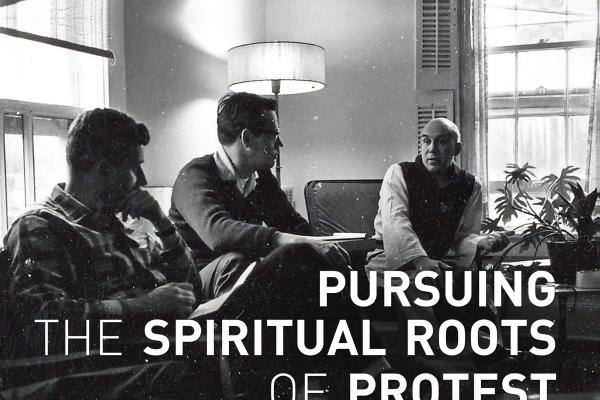

IN NOVEMBER 1964, as the long Cold War heated up again, this time in Vietnam, Trappist monk Thomas Merton set forth a koan to 14 peacemakers: “By what right do Christians protest?” For three days, these activists and theologians—famously uniting Catholic and Protestant faith traditions—met with Merton in the Kentucky hills, grappling with how and why Christians should resist the violence of war.

Historian Gordon Oyer has re-created this meeting so pivotal to the peace movement and—most important—assessed its meaning for our time. The historic retreat is meticulously sourced with detailed textual analysis of the presenters at the retreat and the writers who influenced them. Particularly impressive is the lucid summary of the era and the delicacy and respect with which the author treats cultural and doctrinal differences among the participants.

Ecumenism in peace work is thankfully common today, but in the early ’60s the blending of faith traditions at the retreat was groundbreaking. Even more revolutionary were the two Masses the group celebrated together, with Jesuit priest Dan Berrigan presiding, everyone in the group receiving communion, and John Howard Yoder, a Mennonite theologian, preaching at the second liturgy. (Both practices were proscribed at the time.)

Attendees included Phil Berrigan, later one of the creators of the Plowshares actions for nuclear disarmament, and A.J. Muste, dean of the U.S. peace movement at the time, with years of experience in War Resisters League, the Committee for Nonviolent Action, and the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). FOR’s Paul Peachey and John Heidbrink were instrumental in initiating and organizing the retreat, although neither of them could attend in the end. (Neither could two other invitees—Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King Jr.)

The retreat forged ties between the mainly Protestant FOR and the growing Catholic peace movement. By the end of the year, the Catholic Peace Fellowship had opened an office in Manhattan, under the auspices of FOR, where Catholic Workers Jim Forest and Tom Cornell, both present at the retreat, organized against the Vietnam War and counseled men opposed to the draft.

Merton introduced the group to the writings of the French monk Louis Massignon, pointing out that monks fled to the desert to resist the Constantinian marriage of church and state, and so are forever in protest by their very being. He also explicated Jacques Ellul’s critique of technology, which became a retreat touchstone. Dan Berrigan meditated on Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and his concept of a humanity evolving toward God. Yoder’s closing session provided a beacon that continues to guide peaceworkers: The spiritual roots of protest lie in the life and teaching of the incarnate Jesus, who counsels us to resist the principalities and powers of the privileged as he did.

In a compelling epilogue, Oyer ties all this together by asking four contemporary peacemakers to ponder the relevance of the retreat for today’s troubled world. Theologian Ched Myers, Catholic Worker farmer and scholar Jake Olzen, Elizabeth McAlister of Jonah House (widow of Phil Berrigan), and retired Episcopal bishop George Packard comment cogently on several questions posed during the retreat discussions.

All reaffirm a continuing spiritual practice and a resistance culture grounded in community, particularly community with the marginalized, a concept stressed in the retreat. And Yoder’s simple conclusion that our roots are in the nonviolent Jesus has become the unifying standard for all faith-based resistance, so much so that we now take Christian ecumenism for granted and look to work with Jewish, Muslim, and Buddhist believers.

Oyer writes, “We as a society and a species are nearing the edge of a cliff at warp speed.” We each need to pursue the spiritual roots of protest in this book so we may better resist the culture that threatens to push us off the cliff.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!