Paul

JEWISH NEW TESTAMENT scholar Amy-Jill Levine claims that all religions are a little bit supersessionist. Christian supersessionism — which understands God’s covenant with Christians to nullify God’s covenant with the people of Israel — has been so mainstream throughout most of Christian history that it has hardly required articulating. It was just the anti-Jewish water in which we swam. Following the Holocaust, however, Christians recognized how much we’d weaponized supersessionism into antisemitism, which provided support for Nazi and white supremacist ideologies and perpetuated anti-Jewish violence. Unfortunately, Levine argues, no exegetical maneuver can fully expunge supersessionism from the New Testament — though many have tried. It’s there. And the authority of God’s word in Christian lives keeps its dangerous power ever-present.

Still, Paul’s letter to the church in Rome (which we read this month) contains Paul’s own grappling with these questions. Chapters 9 to 11 — wherein Paul corrects some of the Gentile converts who think God has now rejected the covenant with Israel — comprise the hook on which most contemporary attempts to dismantle supersessionism hang their hat. So, we’ll pay special attention to these.

This isn’t going to be an easy fix — particularly for Christians (like me!) who want to hold fast to the gospel, atone for complicity with antisemitism, and stand in solidarity with Palestinians under occupation. Still, I trust God’s promises: I believe both that God’s covenant with Israel endures and that Jesus is the Messiah. So, this month, we are going to sit with the discomfort of failing while attempting the impossible. Because, in trying, we might find a new way through.

How the “welfare state” is designed to subsidize affluence rather than fight poverty.

WE HAVE SEVERAL readings this month where God creates something out of nothing — or at least out of pretty limited materials. In the opening chapters of Genesis, we see creation birthed from God’s imagination and curiosity. In the story of Sarah and Abraham, a child is conceived in a womb so postmenopausal that the now-pregnant woman can’t help but laugh (Genesis 18). A well appears from nowhere to quench the thirst of a dying woman and her child (Genesis 21:19). God “calls into existence the things that do not exist” (Romans 4:17). And God turns death to life through the mysteries of resurrection (Romans 6:1-11).

This month’s lectionary readings make God’s continuous creation — as well as God’s continual renewal of creation — explicit. But the fact is, once we’re looking for it, all of scripture tells these stories of renewal. God is always creating, re-creating, and reimagining our world. God is always making a way where there was no way before. God continually turns death to life. And, just as importantly, we are called to participate in God’s divine practices of continuous creation, in God’s own divine practice of everyday resurrection.

As we exit a series of some of the higher holy seasons in the liturgical year — Epiphany, Lent, Easter, and Pentecost — June quiets down from such intensity. The slower pace to which (in some places) the warm summer sun calls us can inspire us to seek out everyday resurrection wherever God hides it. How is the Spirit calling you to partner with divine practices of renewal, with everyday resurrections?

THE ROUGH VOICE of the aging priest is muffled as he bends forward to touch his head to the marble altar. Face down is better than face out, he thinks, where his failure is on full display.

The near-empty church extends into shadow. A handful of worshippers avoid close contact. They grip the wooden pews with desperation, the half-drowned scrambling for a gunwale. “The hulk of the shipwreck behind them,” as the poet says. Their children won’t come to church, the hypocrisy too much to bear. He knows the saints in high niches are no match for the idols in their children’s pockets, provide no relief from their hollowed-out fatigue. He glances up. I am the captain of this ship, he thinks, and we are going down. The bread sits lifeless in the paten. The wine a flatline. Instead of Christ at the Last Supper, the priest recalls Odysseus clinging to the fig tree while the sea greedily sucks down his ship and men. Is that what you get for rustling the gods’ cattle, he wonders.

People have often said to me, “If Paul came back today, what would he be most shocked at in today’s church?” And I say, unhesitatingly, our disunity — not just the fact that we’re not united, but the fact that we don’t care.

Caviezel went on to say, “There is one choice, it's Christ. And that doesn't mean it's gonna be easy ... Certainly wasn't easy for Jesus, certainly wasn't easy for Luke or Paul. So what does our faith do? In these tough times, not good times, the world in good times can handle it great. In bad times, what happens to us? That's when we become beautiful. That's when the world goes, how can you love?”

Though they gave respectable answers, I was amazed no one directly quoted the Christian Gospels on the subject.

The Gospel of Mark provides one saying of Jesus directly applicable to this situation. But when we examine subsequent uses of that saying in the other Gospels, we can see why none of the 60 Minutes interviewees dared quote that particular verse.

It is the tragedy of Christianity that the first hate crime in our constellation of texts is Matthew’s, in his telling the story of the passion. Jesus was a great teacher, an inspiring healer, and a man whose radical compassion touched everyone — women without honor, under-employed fisher folk, Roman soldiers, gentiles, Samaritans, scholarly Pharisees. The hearts of Palestinian Jews flocked to him, and this terrified the Romans. They tried to abort his movement by making his death a spectacle of cruelty and unutterable degradation.

While they told Moses that, “All the words that the Lord has spoken we will do” (Exodus 24:3), in the end they turned to idols and broke God’s laws. By the time we get to First Samuel, we hear the people clamoring for an earthly king so they could be like other nations (1 Samuel 8:4-22). They thought life would be better if they shook up their system of government, so they ditched the judges and looked for an outsider. In the end, they got exactly what they asked for – a king named Saul who was wicked and moody and paranoid.

Stop me if you’ve heard this story before. It’s familiar to many. The story features a culture that treats people like commodities, valuing them only insofar as they produce wealth.

“We do not remember days,” the Italian poet Cesare Pavese said, “we remember moments.”

Pavese’s words have come to mind often as I’ve thought about Pope Francis’ historic visit to the United States, particularly when people have asked me what the “best part” of covering the papal visit was for me.

My answer is always the same: hands down the best part was watching people see (and sometimes meet) Pope Francis in person for the first time.

“REJOICE IN THE LORD ALWAYS.” “Do not worry about anything.”

“I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.”

Verse fragments such as these, in the midst of a warm, fuzzy letter the Apostle Paul wrote to the house churches in Philippi, sustained me through high school and beyond. Indeed, the entire letter is saturated with joy. Philippians has been a source of great comfort to many Christians over the centuries.

It is clear that Paul had a close friendship with the believers in Philippi. A major purpose of the letter was to thank them for sending one of their own, Epaphroditus, with a gift for Paul. Sadly, the messenger became very ill while with Paul, but now that he has recovered, Paul is returning him to Philippi, along with the letter (2:25-30; 4:15-18).

Less clear are the political assumptions and harsh realities that frame this encouraging missive. Paul lived and traveled within the mightiest empire the world had known up to that point. He carried his gospel message thousands of miles on Roman roads built for military conquest. At the same time he challenged the very foundations that supported this empire, and his activism was perceived by political authorities as a threat. Paul paid for this by suffering in a Roman prison (1:13) and did not know if he would survive his ordeal or not (1:21-24).

The fate of the Temple of Artemis, the fate of any temple, is one that need not be feared. Death, and collapse, have lost their sting. This process of decay is not an inherently ugly one. There was beauty in those remaining stones and still value in the ones that had already returned to the ground from whence they had been pulled.

Whether human or stone, from dust we have come and to dust we shall return.

Some years ago, Carl Jung told the story of a man who asked a rabbi why God was revealed to many people in days of old, but now nobody sees God.

“Why is this?” he asked.

The rabbi answered, “Because nowadays no one bows low enough.”

Perhaps we are looking for God in all the wrong places. In this video, Sister Margaret goes to prison. She is not Jesus. She is not God. But she believes God is there in Riker’s Island, “home” to 1300 prisoners, half of them teenagers. She listens to their stories.

“My father walked out on us ... I messed up ... I had no one to back me up.”

Their stories changed her.

"I don’t know what it’s like not to be loved. I don’t know what it’s like to be abused, to be abandoned,” she says.

She is really saying, “I didn’t know before what it’s like to be so far down.”

These prisoners are teaching her even as she is counseling and encouraging them. Those men in Riker’s Island would probably be surprised to hear that Paul was a prisoner when he wrote this week’s lectionary selection, a letter to the Philippians.

Paul teaches a bedrock unity in marriage. Both the Christian wife and husband are members of the Church which is Christ’s body (v30) and have further cemented this with particular devotion to union with each other (v31). Since we have this fundamental unity, a divisive gender identity in marriage or elsewhere is impossible to accept—it sets up barriers where Christ recognizes none.

As such, men inside or outside of marriage must follow Christ’s example in giving of themselves for others, particularly to those who rely and trust on them. This is why domestic violence is such a satanic perversion of masculinity: it replaces a protective, self-sacrificial love with a violent, domineering authority. A relationship which should point to Christ and the Church instead becomes controlled by power and violence.

Paul forces me to think differently about what it means to be a man. I need to reorient my actions in a way that recognizes that Christians, male and female, are all part of one body of Christ. That should push men, especially those in positions of authority, to a love that seeks to build up and to serve rather than domineer. That love, rather than a macho authority, is the true mark of a man.

Do you want to know a secret about working out? Here it is: we don’t grow our muscles in the gym. When we lift weights we perform controlled damage to our bodies; we literally tear our muscle fibers, forcing our bodies to adapt. We improve outside of the gym by consuming healthy foods. To “battle the bulge” requires a commitment to strenuous exercise and healthy eating. All who have enjoyed (or endured) a strenuous workout or have disciplined their dietary practices understand that results are impossible without bodily sacrifice — no pain, no gain.

Furthermore, if it is true that we are what we eat, then Christ-followers ought to take a long, hard look at the kinds of things we are putting into our bodies. Paul’s words to the Christ-followers in Rome offer us some food for thought (pardon the pun; couldn’t help myself).

Paul beseeches us to present our bodies as living sacrifices, that is, to submit our lived reality to the standards that God deems acceptable. Such a way of being in the world is deemed reasonable — spiritual even, as the NRSV translators put it. This is our tangible act of service to God.

My Dear Friend,

It breaks my heart to be the one to tell you this, but I figured you might be more receptive hearing this from me. I think you already know what I'm about to tell you — it's nearly impossible you couldn't know with how loud everyone's whispers have become.

Something is terribly wrong! You are sick.

I know this isn't the news you were hoping for, but it's the truth. With this in mind, I feel now, it is more important than ever that I lay things out for you — no matter how much it pains me.

What more perfect a passage to enliven our Earth Day celebrations than Romans 8:20-25?

Paul's letter to the Romans was certainly not an exhortation to deepen creation care by weighting it with environmental justice. It wasn't an exhortation for the middle-class church to listen to the groaning of people under the bondage of environmental racism. It wasn't intended to paint a picture of the intersection of climate change, poverty, and racism.

But we — two evangelical activists — are just foolish enough to give all that a try in this short space!

Our dear Apostle Paul in his letter to the Romans paints a picture of the new age inaugurated by Jesus' death and resurrection. Jesus has taken sin – that which infiltrated the world (5:12), enslaved the world (6:6, 17-18), and brought death and destruction (7:8-14) — and had victory over it. By our death in baptism and resurrection with Christ, we participate in his victory over sin (6:4). This is a new age, we put on our new selves, we live with the (re)new(ed) creation ahead of us.

ONE YEAR MY small group decided to have each member choose a person named or alluded to in the gospels to “follow” during Lent. We researched our people and the customs of that time and reflected individually and collectively on their encounters with Jesus. Then we hosted a community meal for family and friends on the night before Easter. Each member of our group came in character as the person we’d studied and tried to recreate the mood of that frightening, confusing, grief-filled night for followers of Jesus after his death and before his resurrection. After the meal, each of us presented a monologue that tried to project what our person might have been thinking and experiencing at that time.

The attempt to immerse mind, soul, and body into scriptures that I had listened to for much of my life (but perhaps hadn’t really heard) was a transformative experience: It burned away long-held assumptions and revealed new facets of chapter and verse.

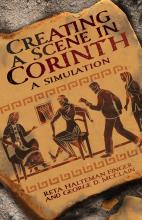

The book Creating a Scene in Corinth: A Simulation, by Sojourners contributing editor Reta Halteman Finger and George D. McClain, provides a useful and fun toolbox for small groups, Sunday schools, religion classes, and even imaginative individuals who want their own full-immersion experience of scripture and biblical scholarship. It invites readers to a deeper understanding of the apostle Paul’s letter to the church in Corinth by using role play to “become” members of the different factions of that community as they hear Paul’s words read for the first time. The authors assert that “as we more clearly experience what Paul meant in the first century, we can better understand what his writings mean in our 21st century context.”

LUKE'S SECOND VOLUME, the Acts of the Apostles, tells the story of what happened to Jesus’ followers after they received spiritual power to be his witnesses “in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

Beginning in Jerusalem, the movement proceeds north and west, eventually tracing Paul’s journey to Rome. But the plot takes one big detour along the way, heading south to the mysterious lands beyond Egypt, carried by a person more foreign and unusual than any other in Luke’s vast cast of characters. Only divine intervention orchestrates the encounter between the Jewish Hellenist Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch in Acts 8:26-40.

What is the main thrust of this missionary story? Is it geography—a foray into “the ends of the earth” long before Paul reaches Rome? Is it religious ethnicity—the first God-fearing Gentile believer converting, even before the Roman centurion Cornelius? Is it the man’s undeniable African origins—straight from the lands of Nubia and Cush? Is it his wealth and connections to royalty that will enable him to bring Jesus’ gospel to Africa?

Luke likely included this story for all these reasons, but the text itself points over and over to what must be the driving force of Luke’s inclusive theology in this account—the rider in the chariot is not referred to by Luke as a man. Luke calls him a “court official” and a eunuch (8:27), and later calls him a eunuch four more times, but never a “man.” He has been castrated before puberty and trained to take sensitive positions not entrusted to males. He is beardless with a higher voice. Torn from his birth family and enslaved at a young age, he has no family of his own. Loyal only to his queen, he is “in charge of her entire treasury.”