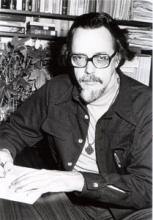

John Howard Yoder

Immoral exemplars leave us to grapple with a host of difficult ethical questions. Among these are certainly questions about their status and the value of their work. But these are not the only — or even the most important — issues. We also must consider the concerns of survivors, the integrity of our most treasured traditions and institutions, and how our response might contribute to a more just world. When we focus solely on the status of the tainted thinker and their work, much of the ethical picture fades from view.

[John Howard] Yoder suggests that texts such as “Do not be anxious” may be given in the context of the fallow year and that the prayer “Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors” should be interpreted far more literally than has usually been the case in praying our Lord’s prayer.

For me, the question of what to do with Yoder is not only an academic issue but a personal one. I was Yoder’s graduate assistant — and would be his next-to-last — for two years. Academically, how I teach my “War and Peace in the Christian Tradition” course is indebted in great extent to what I learned from him. As evident in numerous footnotes, my scholarship and publications, including for Sojourners, over the last two decades on just war and just policing also owe a lot to both his research and his mentoring.

Nevertheless, after this semester, I am leaning towards Blanton’s recommendation of setting Yoder’s work aside, at least for the foreseeable future. I think it is now possible to rely on the work of others for persuasive defenses of nonviolence and for strong critiques of Niebuhrian realism. I struggled over whether to use one of his books or essays in my course this semester. I hesitated to say anything about Yoder’s misconduct to my students. It took me a while before I did so.

What to do with Yoder? I’m not sure.

Yoder became a superstar at the Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Elkhart, Ind., where he taught for 24 years, respected and admired by fellow church members and Christians who were not Mennonite. Yet, at the same time, he was preying on women, many of them his students. A report has revealed a range of sexual offenses, starting in the mid-1970s, as well as the church’s efforts to keep them quiet.

Christian men - males who are caught up in the ancient, raw, and radical Jesus movement, this is to you:

It's high time we say something, do something - good Christian men, stand up. Women are being raped and sexually abused across the world, and we continue to theologically shrug our shoulders. It's just the way it is, we say.

Whether we want to admit it or not, we turn a blind eye to the ways in which our holy scriptures have sanctioned this throughout history.

JOHN HOWARD YODER, who died in 1997, was a theological educator, ethicist, historian, and biblical scholar. He is best known for his 1972 masterpiece The Politics of Jesus, his radical Christian pacifism, his influence on theological giants such as Stanley Hauerwas, and his advocacy of Anabaptist perspectives within the Mennonite community and beyond. Many testify that Yoder’s exposition of the gospel allowed them to grasp radically good news in the life and teaching of Jesus Christ.

There is a dark cloud over Yoder’s legacy, however, that refuses to dissipate. Survivors of Yoder’s sexual abuse and other advocates have renewed their calls for the Mennonite Church, including Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary (AMBS), to revisit unfinished business with his legacy.

On Aug. 19, the executive director of Mennonite Church USA, Ervin Stutzman, announced the formation of “a discernment group to guide a process that we hope will contribute to healing for victims of John Howard Yoder’s abuse as well as others deeply hurt by his harmful behavior. We hope this work will lead to church-wide resolve to enter into lament, repentance, and restoration for victims of sexual abuse by other perpetrators as well.”

My office has two overflowing bookshelves, with more books stacked on top and on the windowsill. But above my desk within easy reach is a small shelf. On it I keep those books I most regularly use in thinking and writing. Here are the top 10.

My office has two overflowing bookshelves, with more books stacked on top and on the windowsill. But above my desk within easy reach is a small shelf. On it I keep those books I most regularly use in thinking and writing. Here are the top 10.

1. The Bible: What can I say about the foundational source of God's guidance in everything? I read or refer to it nearly every day. It was given to us "for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness" (2 Timothy 3:16).

2. The Book of Common Prayer: I am not Anglican/Episcopalian, but there is something in the formal prayers of the traditional liturgy that resonate with my soul. On those days I really don't feel like praying or can't find the words, it's comforting to have a place to turn for inspiration.

Since Mennonite theologian and ethicist John Howard Yoder's death in 1997, I have often wondered what he would have said about the events of these past eleven years.