Faith and Politics

Meaning happens when the purposes of the writer come together with what the reader thinks is important. Since all aspects of any one thing cannot be perceived all at once, we focus our attention on this or that aspect of a thing depending upon what we want to achieve. This is why we can read a particular text many times and find new insights each time. This is also why we cannot agree on what the Second Amendment of the U.S. Constitution means.

On April 11, 1963 Pope John XXIII published an encyclical some initially dismissed as naive and myopic, as too liberal and too lofty. But today, his "Pacem in Terris" is generally lauded as genius and prophetic – well ahead of its time on the issues of human rights, peace, and equality.

As Maryann Cusimano Love, a Catholic professor of international relations, notes, the same year “Pacem in Terris” was published, spelling out the theological mandate for political and social equality for all people, women in Spain were not allowed to open bank accounts, Nelson Mandela was standing trial for fighting apartheid, and Walter Ciszek was serving time in a Soviet gulag simply for being Catholic.

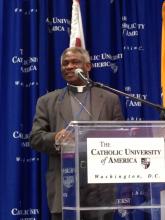

On Monday and Tuesday, the Catholic Peacebuilding Network hosted a two-day conference at the Catholic University of America, commemorating 50 years since the publication of "Pacem in Terris.”

David Kuo was a good friend of mine. After a decade long battle with brain cancer, David passed away last week. He leaves a beloved wife, Kimberly, and two little children.

Because David’s family situation was similar to my own, our whole family was very aware of David’s pilgrimage over these many years and my two boys would want to pray for “your friend David.”

When I first met David, he was known as a rising young star among political conservatives. We met in a hotel gym at a conference we were both attending. Over the workout together, we became friends. David was the exemplary “compassionate conservative” and later joined the Bush White House faith-based office. He was always a truth teller and did that in Tempting Faith: An Inside Story of Political Seduction that warned how politics — on both sides of the aisle — can prevail over and even manipulate faith for political gain.

David always believed that our faith should shape our politics, not the other way around.

This August will mark the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, and there will rightly be much remembrance and celebration of its place in American history. But there is another anniversary that our nation, and especially its Christians, would do well to acknowledge, investigate, and ruminate.

Forty-five years ago yesterday, Dr. King arrived in Memphis, Tenn., to support a sanitation workers’ strike seeking to unionize. He was assassinated the next day — the anniversary we today remember — and in a sad irony our nation began the sanitation of his legacy. Indeed, King’s decision to join the Memphis struggle was just one of many acts that clash with what David Sirota calls the “Santa Clausified” image of King that we pass to our youth.

I recently went back to the Lincoln Memorial to tell the story of how and why I wrote my new book, On God’s Side: What Religion Forgets and Politics Hasn’t Learned About Serving the Common Good. And I reflected on my favorite Lincoln quote, displayed on the book’s cover:

“My concern is not whether God is on our side: my greatest concern is to be on God’s side.”

I invite you to watch this short video, and to engage in the discussion as we move forward toward our common good. Blessings.

ALL EYES WERE fixed on Richard Twiss, the Lakota/Sioux co-founder and president of Wiconi International, who stood center stage at the 2011 Christian Community Development Association conference.

Twiss pulled no punches as he told the truth about the church's role in colonization: The global genocide of indigenous peoples and the eradication of indigenous cultures by requiring people to cut their hair, leave their families, forsake their languages, and forswear their drums. Coaxed to convert or be damned, indigenous people exchanged their own culture for guitars and mission schools in order to be "Christian."

On Feb. 9, 2013, Richard Twiss passed to the other side of life. For many he was a key voice for indigenous people finding a way to reclaim their culture while keeping hold of Christ. While Twiss was a primary voice of the movement, he was also a member of a larger circle of indigenous leaders, each of whom has played his or her part to establish and spread the good news of cultural reconciliation after "500 years of bad haircuts," as Twiss liked to put it.

Twiss had enormous impact on the indigenous "contextual ministry" movement. "Contextualization means to present the good news of the shalom kingdom of Jesus Christ in a way that people can understand and relate to in their own cultural context," explained Randy Woodley (Keetoowah Cherokee), distinguished associate professor of faith and culture at George Fox Evangelical Seminary.

IN THE PAST 20 years, the world has witnessed the death of social contracts. We have seen a significant breakdown in trust between citizens, their economies, and their governments. In our own country, we can point to years of data painting a bleak picture of the confidence Americans have in any of our traditional institutions.

Former assumptions and shared notions about fairness, agreements, reciprocity, social values, and expected futures have all but disappeared. The collapse of financial structures and the economic crisis that followed not only caused instability, insecurity, and human pain; they have also produced a growing doubt and basic distrust in the way the system functions and how decisions are made.

This year, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, we looked to the future and asked, "what now?" At a key session—"The Moral Economy: From Social Contract to Social Covenant"—a document was announced that kicks off a year-long global conversation about a new "social covenant" between citizens, governments, and businesses.

It is really a call for worldwide discussion about what values are needed to address the many difficult challenges the world is now facing. Inequality, austerity, retrenchment, maldistribution, conflicts over resources, and extreme poverty all raise questions about our values.

COLUMBUS, Ohio — Thirteen state attorneys general are urging the federal government to broaden religious exemptions for private businesses under the White House’s contraception mandate, claiming the policy violates religious freedoms.

Put simply, the group believes any employer who says he or she objects to contraception should not have to provide contraceptive coverage.

Cardinal Timothy Dolan, the top U.S. Catholic prelate, says the Roman Catholic Church has to make sure that its defense of traditional marriage is not reduced to an attack on gays and lesbians.

Dolan is president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and last month was reputed to have gathered some votes in the Vatican conclave where Pope Francis was eventually elected.

He made his remarks on two morning talk shows on Easter Sunday, just days after the Supreme Court heard arguments in two same-sex marriage cases.

The conversation yelling match around gun control is exhausting — both in terms of the ethical boundaries each side will breach to advance its cause, and the way our rhetoric has turned into an exercise in “crash-testing:” we always hit a wall in talking our good sense to the Dissenters, but are content to back up, add force, and try again. Because “One day, THEY will see the light. One day, THEY will become US”…

… crash!

The more gun violence we experience as a nation correlates to our panic in pursuit of the common good, however we define it. And get too many panicky people in a room – people who are certain they are right – and watch how skillfully they evade progress. I am a pastor in Chicago and I speak on behalf of all who serve in neighborhoods where violence has become the rule and not the exception: I am tired of you hitting the wall.

This course of action and righteous disrespect of Those-With-Their-Heads-You-Know-Where will not make us masters or better neighbors. It has made us dummies. And while we are arguing, our children are losing. In Chicago, and Baltimore, and Detroit, and Newtown, and in Washington. They are losing because we are competing to see who can make the wall topple over the other first. Because we are arguing over rights from the wrong perspective.

This week a large number of Americans are celebrating Holy Week, leading up to Easter Sunday. Churches will be packed with both the regulars as well as the once- or twice-a-year worshippers for the "Super Bowl of Sundays" to celebrate Christ’s victory over death and sin and his glorious resurrection.

In the midst of an exasperating and polarized political debate around the U.S. budget, our national and political leaders can learn valuable lessons from Holy Week. Whatever your faith background may be, we could all benefit from a greater commitment to the humility, shared sacrifice, and hope that Holy Week embodies. An extra dose of humility, sacrifice, and, ultimately, hope represent the balm that could bridge many of our ideological differences and resolve the current political impasse around the budget that has paralyzed our political system and divided the nation.

A revealing thing happens when you remove yourself from the daily drum of politics and become a mere observer. I did just that last year, during some of the most divisive moments of the presidential election. Sitting back and watching the deluge of insults and accusations that feeds our political system, I witnessed the worst of us as a nation. And I came to the conclusion that it’s time to reframe our priorities.

When did we trade the idea of public servants for the false idols of power and privilege? When did we trade governing for campaigning? And when did we trade valuing those with the best ideas for rewarding those with the most money?

We’ve lost something as a nation when we can no longer look at one another as people, as Americans, and — for people of faith — as brothers and sisters. Differing opinions have become worst enemies and political parties have devolved into nothing more than petty games of blame.

During a three-month sabbatical, observing this mess we’ve gotten ourselves into, I prayed, meditated, read — and then I put pen to paper. The resulting book gets to the root of what I believe is the answer to our current state of unrest. It is not about right and left — or merely about partisan politics — but rather about the quality of our life together. It's about moving beyond the political ideologies that have both polarized and paralyzed us, by regaining a moral compass for both our public and personal lives — by reclaiming an ancient yet urgently timely idea: the common good.

Secretary of State John Kerry is calling for the release of an Iranian-American minister from a Tehran prison, a welcome step for advocates who had accused the State Department of being “AWOL” on the case.

“I am deeply concerned about the fate of U.S citizen Saeed Abedini, who has been detained for nearly six months and was sentenced to eight years in prison in Iran on charges related to his religious beliefs,” Kerry said in a statement released on March 22.

“I am disturbed by reports that Mr. Abedini has suffered physical and psychological abuse in prison, and that his condition has become increasingly dire.”

Mr. President, just like the many other visitors that we receive here in this land, we would do our best to overwhelm you with our cultural hospitality and our traditions. I would seize this opportunity to not only welcome you to visit Bethlehem, but also to welcome all U.S. citizens to visit my small city.

I invite you, Mr. President, to be in my city within the nation that has a dream of liberty — a dream that goes in rhythm with all nations’ right of self-determination. We have embraced, as other nations, our pursuit of democracy, human development, and security. We have tumbled through our pursuits and have made mistakes, and because like all humans, as part of our human nature, we slip. We have built, learned, developed, and made our existence known to all nations.

Mr. President, I hope that in your visit you would not only enjoy the blessings of the Holy Land, but be encouraged to return and experience this city to its fullest. After you finish your presidency you will be able to visit without a big security escort and you will enjoy wandering the old streets and spending time in the old city of Bethlehem when you come back with your family.

(Note: This post contains some frank and graphic discussions of sex and sexuality.)

Two boys from a Steubenville Ohio high school (I’ve opted not to use their names, though they are readily publicized by other media) have been sentenced to time in a juvenile detention center for the rape of a 16-year-old classmate who was reportedly so drunk at a party that she could no longer stand on her own. Aside from “digitally” raping the girl with their hands, reportedly multiple times, one of the boys took photos of the girl without her clothes, shared them via social media, and both young men bragged about the incident to their social networks following the incident.

As the father of both a boy and a girl, I was particularly angered and disturbed by this story. The very fact that such things happen in a supposedly civil society is a stark reminder that we have only a tenuous hold on the well-being of our kids once they leave our sight. We can only hope and pray that we’ve empowered them with the sense of autonomy, respect, compassion, and restraint to keep them either from becoming victims of such violations, or perhaps even perpetrators of it themselves.

But once I get beyond my initial feelings about the whole situation, I’m left wrestling with a number of questions that still feel terribly unresolved.

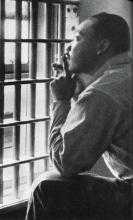

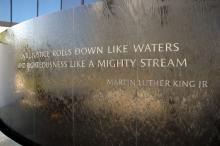

A half a century after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. penned “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King’s prophetic words continue to reverberate. In “To Redeem the Soul of America” (April 2013), author and historian Vincent G. Harding recounts his time with King and explains how King’s “living letter” impacts each of us today.

Watch this video to learn more about King’s historic letter.

On Good Friday 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. led a nonviolent march through the streets of Birmingham, Ala., to draw attention to the injustices of segregation. Arrested for marching without a permit, King composed “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in response to eight white ministers who criticized the timing of the civil rights demonstrations. Rebuking the clergymen for not taking a bolder stance against segregation, King declared that “Justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

THE CHURCH IS locked in a polarized debate around same-sex relationships that is creating painful divisions, subverting the church's missional intent, and damaging the credibility of its witness. We've all heard the sound-bite arguments. For some, condoning or blessing same-sex relationships betrays the clear teaching of the Bible, and represents a capitulation to the self-gratifying, permissive sexual ethic of a secularized culture. For others, affirming same-sex relationships flows from the command to love our neighbor, embodies the love of Jesus, and honors the spiritual integrity and experience of gay and lesbian brothers and sisters.

The way the debate presently is framed makes productive dialogue difficult. People talk past one another. Biblical texts collide with the testimony of human experience. The stakes of the debate become elevated from a difference around ethical discernment to the preservation of the gospel's integrity—for both sides. Lines get drawn in the ecclesiastical sand. Some decide that to be "pure" they must separate themselves spiritually from others and break the fellowship of Christ's body. Then the debate devolves into public wrangling over judicial proceedings, constitutional interpretations, and property ownership. Meanwhile, the "nones," those who are walking away from any active relig-ious faith, find further confirmation for their growing estrangement.

Mirroring the dynamics of contemporary secular politics, the debate is driven by small but vocal minorities with uncompromising positions at one end or another of the spectrum. For the majority in the middle, who may be unclear about their own understandings, exploring their questions is made difficult because of the polarized toxicity of the debate. Further, those in positions of leadership in congregations or denominations come to regard the controversy over same-sex relationships as the "third rail" of church politics. They don't want to touch it. I know this because I've been there myself.

In January 2011, members of Christian Churches Together in the U.S.A. met in Birmingham, Ala., to examine issues of domestic poverty and racism through the lens of the civil rights movement and by reading together Martin Luther King Jr.'s "Letter from Birmingham Jail." As they gathered in the 16th Street Baptist Church under the beautiful Wales Window portraying the black Christ, which replaced the window blown out when the church was bombed in 1963, these contemporary church leaders, representing the broadest Christian fellowship in the country—36 national communions and seven national organizations, including Sojourners—realized that apparently no clergy had ever issued a response to King's famous letter, even though it was specifically addressed to "fellow clergymen [sic]." In 2013, to mark the 50th anniversary of King's letter, Christian Churches Together released its thoughtful response, which we excerpt below. —The Editors

WE CONFESS. As leaders of churches claimed by more than 100 million Americans; as Catholics, evangelicals, Pentecostals, Orthodox, Historic Protestants, and members of Historic Black denominations; as people of many races and cultures: We call ourselves, our institutions, and our members to repentance. We make this confession before God and offer it to all who have endured racism and injustice both within the church and in society.

As church leaders, we confess we have tended to emphasize our responsibility to obey the law while neglecting our equal moral obligation to change laws that are unjust in their substance or application. All too often, the political involvement of Christians has been guided by the pursuit of personal or group advantage rather than a biblically grounded moral compass. We confess it is too easy for those of us who are privileged to counsel others simply to "wait"—or to pass judgment that they deserve no better than what they already have.

We confess that we are slow to listen and give legitimacy to those whose experience of race relations and social privilege in America is different than our own. We keep the "other" at arm's length to avoid hearing the call to sacrifice on their behalf. Our reluctance to embrace our "inescapable network of mutuality" underscores Dr. King's observation that privileged groups seldom give up their advantages voluntarily. For example, it is difficult to persuade most suburban Christians to demand that they strive for the same quality of education in our cities that they take for granted in their own schools. To the extent that we do not listen in love, our influence in society is limited to "a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound."

AT TIMES IT SEEMS VERY HARD to realize that half a century has passed since my late wife, Rosemarie, and I were in Birmingham, Ala., living out a part of our years of service as representatives of the Mennonite churches of America to the Southern freedom movement—that historic black-led struggle for the expansion of democracy in America (inadequately labeled "the civil rights movement").

It was in the midst of those powerful days, in the late winter and early springtime of 1963, when our extraordinary people's movement was spreading to dozens of communities across the South, with some important reverberations in the North, and across the world as well. Usually initiated by courageous home-grown black leaders such as Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth of Birmingham and Victoria Gray of Palmers Crossing, Miss., the determined local groups often called upon national or South-wide organizations to help them in their campaigns.

Late in 1961, Shuttlesworth, who was part of the King-led Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), asked Martin Luther King Jr. and SCLC to come help the Birmingham movement. It faced a level of continuing white terrorism that led the black community to call their city "Bombingham," referring, of course, to the deadly violence they encountered whenever they attempted to challenge the white segregationist powers who were determined to keep black people in a submissive, separate, and dominated role.

When King and SCLC decided to respond to Shuttlesworth and move onto the Birmingham scene, Rosemarie and I were already friends and co-workers with Martin and Coretta, and King asked us to come participate in the struggle for the transformation of Birmingham. So we were present and in the line of marchers when King, his co-worker Ralph Abernathy, and others were arrested in early April 1963.