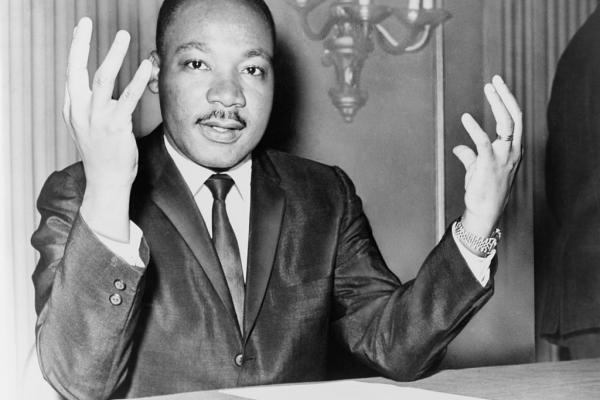

This August will mark the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, and there will rightly be much remembrance and celebration of its place in American history. But there is another anniversary that our nation, and especially its Christians, would do well to acknowledge, investigate, and ruminate.

Forty-five years ago yesterday, Dr. King arrived in Memphis, Tenn., to support a sanitation workers’ strike seeking to unionize. He was assassinated the next day — the anniversary we today remember — and in a sad irony our nation began the sanitation of his legacy. Indeed, King’s decision to join the Memphis struggle was just one of many acts that clash with what David Sirota calls the “Santa Clausified” image of King that we pass to our youth.

Read the Full Article