IN 2012, I was a U.S. State Department officer deployed to Turkey to work with the Syrian opposition. It was an opportunity to support Syrian activists waging a remarkable popular struggle against an authoritarian government that had responded to peaceful protest with bullets and torture. For nearly a year, Syrian Sunnis, Christians, Kurds, Druze, Alawites, and others used demonstrations, sit-ins, resistance music, colorful graffiti, consumer boycotts, and dozens of other nonviolent tactics to challenge the Bashar al-Assad administration. But the nonviolent movement was unable to remain resilient in the face of brutality, external support for civil resistance was weak, and finally Syrians took up arms. This played into Assad’s hand. Death, displacement, and destruction skyrocketed. Extremists exploited the chaos. The Syrian nonviolent pro-democracy forces were inspired and courageous but lacked organization and adequate support to prepare them for the long haul. This haunts me to this day.

I’ve worked around the world with scholars, activists, policy makers, and faith communities to design effective support for nonviolent struggles to defend and advance freedom and dignity. I’ve been mentored by leaders of the U.S. civil rights movement, the greatest pro-democracy movement in our history, whose strategic campaigns to dismantle racial authoritarianism hold great relevance today.

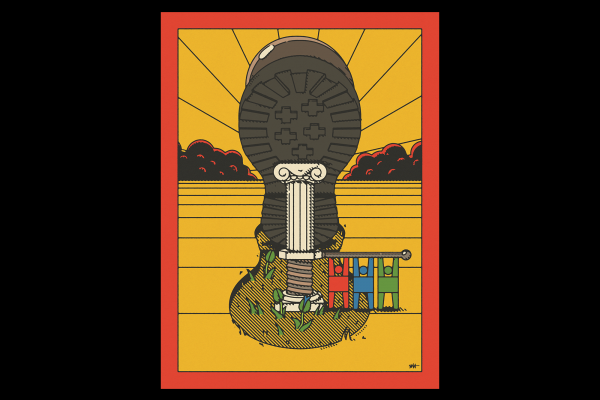

As we head into the 2024 election, the risks to freedom and democracy are higher than they’ve been for decades. Religious communities who understand that democracy is the best modern governing system for protecting religious freedom and advancing shared values have a critical role to play as partisans for democracy.

A People’s Government

DEMOCRACY IS THE delicate balance of collective self-rule (majority rule) and civil liberties (minority rights). For a vibrant, multifaith democracy to thrive, we must reject attempts to concentrate government power in the hands of a few or with those who are not constitutionally accountable to the governed.

What is the role of faith communities in expanding the ecosystem of democratic change? How do we limit the corrosive properties of unaccountable power? Throughout U.S. history, religious ideas, people, institutions, and forms of worship have been used to advance and to undermine a form of government that is, as Abraham Lincoln put it, “of the people, by the people, for the people.” Religious communities have provided moral cover to authoritarian regimes and have been the soul of successful pro-democracy and freedom movements. Expanding shared power through enfranchisement and other democratic practices can reinforce the basic Judeo-Christian principle that each person is made in the image of God. Because each person holds God’s image, each is afforded universal rights and responsibilities in exercising their civil liberties and promoting the common good.

Churches can bring their moral and symbolic power, organizational and communications networks, multiparty congregations, and a faith-rooted, disciplined capacity for nonviolent resistance to the broad-based, pluralist social movements that are key to advancing democratic governance.

stephan_spot_1_1.png

The New Authoritarians

SINCE 2015, THE U.S. “freedom score” has fallen from 92 to 83, lower than democracies in western Europe who have broadly similar political histories, according to global democracy watchdog Freedom House.

While Americans continue to benefit, albeit unequally, from a rule-of-law tradition and strong freedoms of expression (including religious freedom), anti-democratic actors have eroded voter-accountable institutions. This erosion breeds a lack of trust in institutions and is exacerbated by those who have abandoned democratic norms; partisan pressure on an independent public electoral process (made worse by the 2010 Supreme Court decision in favor of Citizens United); and abuse and inequities in the legal system that have failed to deliver “equal justice under law,” a core tenet of democracy.

The U.S. is not alone. Freedom House documents 18 consecutive years of declining freedom and rising authoritarianism globally. As of 2022, for the first time in more than two decades, more people live in “closed autocracies,” where citizens do not have the right to choose their chief executive or legislature in a multiparty system, than live in “liberal democracies,” where citizens elect their leaders, enjoy both individual rights and protected minority rights, are equal under the law, and have a government constrained by rule of law.

In the past, democracies failed because of revolutions or military coups. That’s rare since the end of the Cold War in the 1990s. Democracies don’t fall overnight — they slowly fade away, as Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt unpack in Tyranny of the Minority: Why American Democracy Reached the Breaking Point. Now, a country’s values, principles, and democratic norms are undermined by elected leaders, rather than by a coup of unelected leaders.

Certain leaders in Hungary, Brazil, Turkey, Venezuela, Israel, and the United States were brought to power through democratic elections and went on to systematically undermine democratic norms and institutions. These officials followed an “authoritarian playbook.” Built off social, political, and military strategies of successful tyrants throughout history, the playbook hinges on an inherent contradiction: Only one leader or party can save us, and those leaders need the complicity of many.

Market globalization, which rose precipitously in the 1990s, has caused extreme economic inequality while intensifying social disorientation and loss of local identity in many communities. Populist leaders exploit this fear and lack of control, pitting the concerns of ordinary people against unfeeling “elites” and targeting cultural tension points. They scapegoat a shifting “other” (ethnic, racial, or religious minorities, immigrants, gender minorities, economic class divisions) and promise simple solutions that only they can deliver.

Anti-democratic leaders often introduce partisan divisions into independent, nonpartisan institutions, such as law enforcement and election administration, to weaken them and foment distrust and uncertainty. They spread disinformation (such as the “big lie” that the U.S. presidential election in 2020 was “stolen”) to destabilize trust in facts and disrupt commonly held understandings. They destabilize a “balance of power” in governments, expanding executive power through emergency powers, pardons, replacing nonpartisan civil servants with loyalists, and filling vacant appointments without due process. They quash dissent, denigrate unfriendly press, criminalize protest, attack education, and revise history. They marginalize and blame vulnerable communities, including historically repressed minorities. They change election laws to reduce ballot access, enable partisan interference in vote counting and certification, and denigrate or attack voters and election poll workers. They use linguistic “dog whistles” to create an atmosphere of fear and stoke social violence that threatens real or potential opponents. These strategies make it easier for an authoritarian leader and movement to divide, conquer, and rule without accountability.

Twisting Religion

FAR-RIGHT AUTOCRATS frequently draw on conservative religious values that favor hierarchy. They emphasize patriarchal family structures and unequal gender norms, mobilizing supporters against a scapegoat to solidify their power. Today’s authoritarian leaders center male power and use the power of the state to undermine the democratic freedoms of women and LGBTQ+ people through legislation that targets women’s bodily autonomy and erases protections for minorities. By conflating the “traditional family” with the nation, autocrats can justify these attacks as defense of the family and, by extension, promoting national glory.

Autocrats also adapt religious frames, symbols, and messages to make patriotic appeals. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán frequently uses his interpretation of Christian values to justify xenophobic and anti-immigrant policies. Those policies were given moral weight by Catholic leaders in Hungary, such as Bishop Lázló Kiss-Rigó of Szeged, who said “the more migrants that come, the more Christian values will be watered down.” Orbán’s policies and tactics are serving as a model for some U.S. politicians.

Brazil’s far-right leader Jair Bolsonaro, raised Catholic and baptized in the Jordan River by an evangelical pastor prior to his 2018 election, focused on hot-button issues in the lead-up to the 2022 election, including abortion, gender roles, and homosexuality. Bolsonaro, who had strong backing from evangelical Christians in Brazil, anchored his campaign in religious events, services, and marches where he was “blessed” in front of thousands of supporters. After losing the election, Bolsonaro tried to overturn the results in a January 2023 coup attempt supported by prominent backers offormer U.S. president Donald Trump.

And in the U.S., Trumpism, with its normalization of political vengeance, nativism, and white nationalism, is supported in no small part by religious actors and institutions. Polling from this year shows that 67 percent of white evangelicals in the U.S. continue to have the most positive opinion of Trump among religious groups. White Catholics follow closely with 51 percent favoring Trump.

Many white evangelical churches’ symbols, slogans, rituals, and communications channels have routinely promoted anti-democratic practices and actions, such as the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, where Christian iconography featured prominently. Public dissenters, such as prominent conservative evangelical Russell Moore, who broke ranks by excoriating Christians involved in the 2021 insurrection, have been targeted.

The MAGA movement even sells a Trump-endorsed “God Bless the USA Bible” for $59.99 (which many Christian pastors, including conservative evangelicals, have denounced as blasphemous).

stephan_spot_2_1.png

Religious Dissent to Authoritarianism

THANK GOD, RELIGIOUS groups and institutions are not monolithic. As Christian theologian Wes Howard-Brook writes, “Worldly kingdoms seek to expand through violence. God’s kingdom, however, contains no violence. Rather, it bears fruit through the practice of ‘faithful resistance.’” Key to effective strategies against autocrats is severing their religious support. Examples abound.

In 2001, Zambia’s President Frederick Chiluba attempted to change the country’s constitution to run for a third presidential term. Although Chiluba had successfully won previous elections by promoting Zambia as a Christian nation, the three national church bodies for Catholics, Protestants, and evangelicals issued a joint declaration condemning Chiluba’s action. Radio Icengelo, owned by the Catholic diocese of Ndola, carried pro-democracy meetings live on air. When the government banned pro-democracy demonstrations, churches organized pro-democracy prayer gatherings, which the government could not ban.

In Nicaragua, the far-left authoritarian President Daniel Ortega is accused of becoming the same type of dictator that he ousted more than 40 years ago. In 2018, student-led protests sparked a countrywide demand to return to democratic norms. Ortega’s regime brutally repressed this pro-democracy uprising. The Catholic conference of bishops issued an ultimatum to the government demanding that it dismantle paramilitary groups, end police repression, and participate in dialogue. Bishops organized a march for peace and justice that drew tens of thousands to protest Ortega’s violent crackdown. The churches continue to serve as sanctuaries for youth activists. The regime has imprisoned Catholic leaders, including bishops, and closed Catholic media outlets.

In Sri Lanka, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa expanded presidential powers through a constitutional amendment and appointed many of his family members to positions of power. In 2022, a nonviolent uprising challenged his regime. Catholic priest Father Amila Jeewantha Peiris began an interfaith campaign that drew Buddhist, Muslim, and Christian leaders to speak out against the anti-democratic actions and hold religious ceremonies to support the pro-democracy movement. After decades of religious-ethnic conflict, displays of interfaith solidarity played a key role in Rajapaksa’s nonviolent ouster.

Viktor Orbán’s Hungary has been a testing ground for advancing one interpretation of Christian values to justify authoritarian rule. It’s also a testing ground in refuting it. Pastor Gábor Iványi, founder of the Hungarian Evangelical Fellowship, officiated at Orbán’s wedding and baptized his two eldest children. In 2010, Iványi refused to attend Orbán’s inauguration in public opposition to Orbán’s increasingly autocratic — and anti-Christian — policies. During the 2015 European migrant crisis, when Hungary’s Catholic Cardinal Péter Erdő said the church in Hungary would not shelter refugees because it would constitute “human trafficking,” Iványi’s church responded by cooking meals and providing shelter for the unhoused, refugees, and the minority Roma community.

In 2019, Iványi and other religious leaders released the Advent Statement — based on the 1934 Barmen Declaration denouncing the Nazification of German churches under Adolf Hitler — condemning the government’s centralization of power and marginalization of minorities.

“We are calling for resistance to an arrogance of power that makes the concept of ‘Christian Liberty’ a slogan for exclusionary, hate-filled and corrosive policy; a power that destroys the social fabric and eliminates useful social institutions; a power that systematically threatens democracy and the rule of law,” the statement reads. “We are concerned about the arrogance of power that mixes the language of national identity with the language of Christian identity in a manipulative way. We cannot let our freedom, given to us by grace in baptism, be taken away.”

In Brazil, more than 150 Catholic bishops signed a letter in 2020 denouncing the Bolsonaro administration’s actions as “approaching totalitarianism.” In 2021, hundreds of Christian leaders called for Bolsonaro’s impeachment, citing constitutional violations. In 2022, religious groups publicly criticized Bolsonaro’s theocratic messaging and his demonization of women and minority communities. This leadership may have persuaded some religious voters to abandon him in the 2022 election.

All these examples are part of effective pro-democracy campaigns that have drawn on diverse nonviolent tactics. They have alternated between concentrated actions (street rallies, marches, demonstrations) and dispersed tactics (walkouts, strikes, boycotts, and go-slow actions). Widening the repertoire of tactics and drawing on the skills and strengths of diverse groups in society makes it easier to persuade and pressure authoritarianism’s key pillars of support, particularly business, religious groups, civic organizations, and security groups. Democracy movements succeed by using a combination of dialogue and direct action to prompt defections and loyalty shifts within these pillars. When large numbers of people, especially those within influential pillars, remove their social, political, and economic support from autocratic regimes, the grip on power is weakened.

What About the United States?

THE U.S. BECAME a mature democracy in 1965, when the civil rights movement forced full enfranchisement for all citizens through the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Critical to this movement’s success were religious convictions, infrastructure, relationships, and robust rituals. Black churches were the movement’s backbone, offering sacred rallying points, training spaces, information networks, and spiritual sustenance in the face of white supremacist backlash. Martin Luther King Jr. and other faith leaders spoke from their religious convictions, drawing on religious imagery and references, to encourage civil rights supporters. The United Defense League, Montgomery Improvement Association, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the American Friends Service Committee, rooted in religious commitments, brought together religious and secular groups (such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) to organize the movement’s most successful campaigns, including the bus boycotts, lunch counter sit-ins, and freedom rides. The movement laid the legal foundation for a multiracial democracy. (In 2013, however, the Supreme Court gutted key provisions in the Voting Rights Act, playing into the hands of anti-democratic forces.)

Beginning in 2017, faith groups were critical to pushing back against some of the Trump administration’s most egregious anti-democratic practices. They mobilized against Executive Order 13769 (“the Muslim ban”) aimed at drastically reducing the number of refugees allowed into the U.S. They offered sanctuary to primarily Central American immigrants threatened by indiscriminate roundups by immigration police.

In January 2021, religious leaders from across the political spectrum rejected the attempted coup and all political violence, defending the peaceful transfer of power. During the 2022 midterm elections, Faiths United to Save Democracy dispatched several hundred poll chaplains to battleground states to offer unarmed protection to voters, defuse tensions, and offer bipartisan assistance. As of February 2024, more than 300 churches in Florida had created “freedom schools” with Black history programs to push back on Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ efforts to remove diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, block Black history in public classrooms, and ban more than 1,000 book titles focused on race. “One of the first things enslavers did was enact laws to criminalize our ancestors to keep them from reading,” Rev. Rhonda Thomas, executive director of Faith in Florida, has noted.

Ordinary people, when organized and inspired, can spur extraordinary change. Our faith traditions may inspire us — but to be effective we also must be organized, and we must act.

The upcoming election is important. But defeating authoritarianism and building a vibrant, inclusive democracy requires a multifaceted, long-term strategy. Hope for undermining violent extremism lies in successful nonviolent strategies of organized resistance and in those individuals who catalyze action for freedom against seemingly impossible odds. Our churches and religious communities can help form these inspired catalysts.

Faith communities are keepers of ancient wisdom and curators of sacred worship. They also are sources of prophetic nonviolent resistance and a place where we deepen the values for a world in which each person’s dignity is recognized, flourishing is encouraged, and we take responsibility for the thriving of others.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!