Pope Francis wrapped up his six-day trip to Africa in the war-torn Central Africa Republic on Nov. 30 by warning that religious conflicts are spawning civil war, terrorism, and suffering throughout the continent.

“Together we must say no to hatred, to revenge and to violence, especially violence perpetrated in the name of a religion or of God himself,” the pope said in Bangui, the capital.

“Together, we must say no to hatred, to revenge and to violence, particularly that violence which is perpetrated in the name of a religion or of God himself. God is peace, ‘salaam,’ ” the pope said, using the Arabic word for peace.

Given the terrorist attacks of the last few weeks, one might be forgiven for feeling a bit bleak about the human species, its frequent use of violence and its failure to negotiate solutions. We must be hard-wired for violence. Or perhaps “war is a force that gives us meaning,” as Chris Hedges put it in his 2002 book of the same title.

It turns out, however, that we’re evolutionarily wired not for violence but for cooperation.

"The vast majority of the people on the planet awake on a typical morning and live through a violence-free day — and this experience generally continues day after day after day," writes Douglas Fry.

"The real story should be the 13,748 gazillion times human beings default to cooperation and kindness!"

The narrative of a retail event like Black Friday weekend is broken.

What if we could embrace a new narrative? What if that new narrative is really an old narrative just seen with new eyes?

This weekend, the global church is starting Advent, which is a time of preparation for the coming of Jesus. However, we live in a world where Jesus has already entered. How should our lives look different in response to that and as a church be part of bringing the kingdom of God to earth in this Christmas season?

An 80s song told us “video killed the radio star.” The music was catchy and referred to the varied attitudes we all had about technology. What is this? What would we do now? Fast-forward 35 years, and videos are the very technology for which we are so thankful.

Video changes everything.

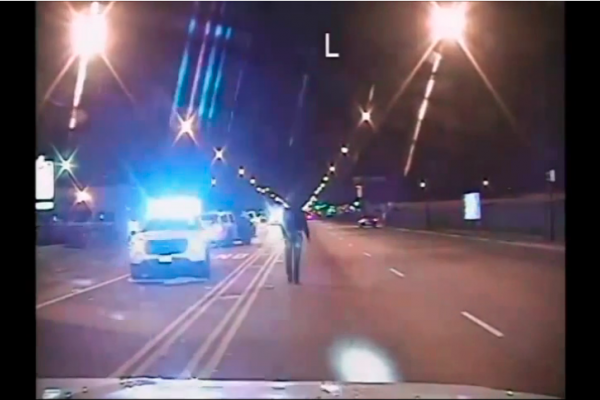

When the Chicago Police Department released the dash-cam video of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald being shot 16 times by one of their own, the city braced for disruption. When we learned of the $5 million settlement to the McDonald family that stipulated the video remain confidential, the city braced for disruption. When residents discovered that footage from a nearby security camera had been deleted by Chicago police, the city braced for disruption. Mayor Emanuel and his team had seen the video, and were afraid of the public reaction.

The clerk in Kentucky is still trying to avoid doing her job while arguing that religion means never having to sacrifice or compromise in any way. The war-on-Christmas crowd is still passing around that story about a red coffee cup lacking snowflakes. Those who believe in an eye-for-an-eye are cheering as bombs fall in the Middle East in response to another horrific terrorist attack. Many Christians are still ignoring the calls for justice coming from the streets of Chicago, Minneapolis, and cities all across the land.

Don’t you want to throw up your hands sometimes? Or maybe just throw up?

Thanksgiving and football—a hallowed American tradition. But according to Concussion, a new documentary by Sony Pictures, potatoes aren’t the only thing getting mashed this holiday.

Concussion chronicles the battle between Dr. Bennet Omalu, a scientist working to expose the dangers of concussion, and the NFL’s powerful attempts to discredit Omalu’s research. When it comes to silencing its critics, wrote Danny Duncan Collum in “America’s Blood Sport” (Sojourners, December 2015), “the NFL may have even more power than Big Tobacco.”

“Taking in refugees at a time of crisis is simply the right thing to do.”

These words from Jeh Johnson, the United States Secretary of Homeland Security, are spoken in a recent video released by the new-media news source ATTN: on Nov. 24. Through simple, yet powerful, illustrations, the video debunks the myths of refugee resettlement in the United States, with specific attention to the Syrian refugee crisis.

After what is being described as "a group of white supremacists" opened fire on protesters near a Black Lives Matter camp in Minneapolis, leaving five wounded, local police are still trying to identify the shooters. On Nov. 24, police took three white men into custody, two of which turned themselves in voluntarily. A fourth suspect was also released, after investigators found the man was not present at the scene of the shooting.

What do you do when you want to balance the budget and don't know how to compromise? Well, if you're Congress, you raid $1.5 billion from a fund set up specifically for crime victims and hope no one notices.

The Victims of Crime Act fund, set up by Congress in 1984, is distributed to states to support local domestic violence shelters, rape crisis centers, and a variety of victim assistance programs for survivors of trauma and crime. The thing is, this is a self-sufficient federal fund — meaning that it doesn't come from taxpayer money but rather the fines and penalties imposed on criminals and offenders.

After more than a year, and an eventual judge order, Chicago police today released a dashcam video showing officer Jason Van Dyke shooting 17-year-old Laquan McDonald 16 times. Police released the video the same day Van Dyke was indicted on first-degree murder charges. He is being held without bail.