Recently, a large wealthy church decided to break up with my denomination. I’m not 100 percent sure I know why. But the no-regrets explanation they wrote implied that religious differences between us were too severe for them to stay committed to our relationship.

Religion has a way of making people do extraordinary things to create peace and unity. It also, as we know well, has a destructive capacity to turn people against one another. It can make us grip our convictions so tightly that we choke out their life. We chase others away, then say “Good riddance” to soothe the pain of the separation. Even more alarming, too many religious people insist on isolating themselves and limiting their imagination about where and how God can be known.

All these realities take on a sad irony when we read about God promising to be outside the walls, present with different people in different places. What does it look like when God defies the restrictions we presume are in place?

Evangelist Franklin Graham is praising Russian President Vladimir Putin for his aggressive crackdown on homosexuality, saying his record on protecting children from gay “propaganda” is better than President Obama’s “shameful” embrace of gay rights.

The Russian law came under heavy criticism from gay rights activists, and from Obama, ahead of the Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia. In response, Obama included openly gay athletes as part of the official U.S. delegation to Sochi.

“In my opinion, Putin is right on these issues,” Graham writes. “Obviously, he may be wrong about many things, but he has taken a stand to protect his nation’s children from the damaging effects of any gay and lesbian agenda.”

Turning part of the message over to church members is the concept behind a new worship model called WikiWorship.

Yes, that’s wiki as in Wikipedia.

The week before each WikiWorship, participants submit questions on religion, ethics, life, or God via the mission’s website. Then Chryst chooses one to spur discussion at each service.

Intending it as a compliment, a friend described my work in in Kiev last weekend as “selling sodas in Ukraine.”

He’s right. I was in the embattled city to represent a company I helped co-found and our Southern California energy drink brand in meetings with more than 10,000 Ukrainian independent business owners.

It was as simple as that and also so much more.

Like Bono, I believe free enterprise is a cure for all sorts of poverty — economic, political, and spiritual.

And as I worshiped I realized creation wasn’t singing with me. I had entered into creation’s ongoing worship of God!

But Scripture speaks of another utterance of nature — a groaning. (Romans 8:19-22) Even as creation worships, it bears the weight of our sin. Our addiction to consumption, our oil drills and oil spills, and our depleted uranium bullets whizzing through theaters of war in countries ravaged, torn apart — both the people and the land. Creation is groaning, even as the trees lift their branches heavenward in worship.

The Genesis 2 story of creation offers a profound picture of humanity’s relationship with the rest of creation in the beginning. In Genesis 2:15 God called humanity to till and keep the Garden of Eden. The Hebrew word for “till” (‘abad) is also translated “to serve” (as a bond servant). The Hebrew word for “keep” (shamar) is most accurately translated “to protect.” Thus, we were called to serve and protect the rest of creation. In the very beginning of our existence, we related to the land as its servants — its protectors. That relationship was full of care, nurture, security, and selfless service.

Feeling the pressure from some immigrants’ rights groups on the record-breaking number of deportations under his administration (2 million by early April), President Barack Obama recently requested a review on his deportation polices. The goal is to see if enforcement can be applied “more humanely within the confines of the law,” the White House said Thursday.

The decision comes after a recent meeting Obama had with three leading Hispanic leaders from the Congressional Hispanic Caucus. The CHC, which is trying to formalize a resolution directed at Obama against deportations, capitalized on the opportunity to vocalize the outcry from the immigration-rights community on the inflated number of deportations that separate loved ones.

“It is clear that the pleas from the community got through to the President,” Gutierrez said in a later statement. “The CHC will work with him to keep families together. The president clearly expressed the heartbreak he feels because of the devastating effect that deportations have on families.”

Acknowledging the detrimental effect of deportations, “The president emphasized his deep concern about the pain too many families feel from the separation that comes from our broken immigration system.”

The president called on Jeh Johnson, DHS Secretary to administer a review of the current enforcement policies.

Obama has also requested a scheduled meeting on Friday with top immigration activists who have been pressuring him to act on immigration. Although the president and his staff has frequently said using executive action is not an option, advocates remain hopeful that the increasing pressure will result in action and see the review as a step in the right direction.

Read full article with details here.

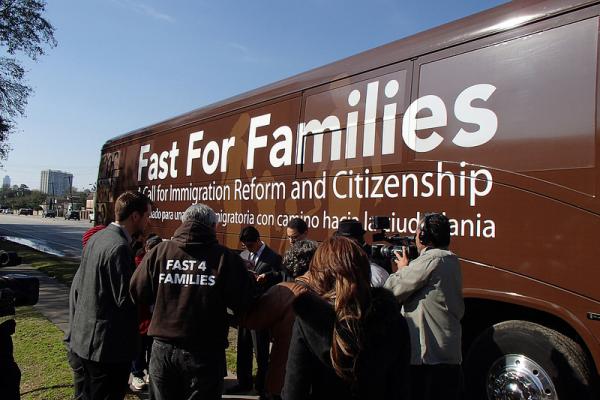

Building on the momentum from last year’s fast on the National Mall, the #Fast4Families campaign has entered into its next phase: a cross-country bus tour. Keeping with the theme “Act; Fast; and Pray until just immigration reform is achieved,” #Fast4 Families kicked off its national bus tour on Jan. 27 from California, where hundreds gathered in support.

The tour across America includes two buses heading through approximately 155 cities in more than 75 congressional districts on northern and southern routes. At each of these 100+ stops, fasters will engage with pro-reform advocates, including faith leaders, who are keenly aware of the moral crisis caused by our broken immigration system.