Some of the discourse surrounding the LA protests reminds me of similar things I heard back in 2014, too. On the one hand, you have centrists and liberal pundits who are lecturing protesters about needing to remain nonviolent — which is quite easy to suggest from a work-from-home station largely insulated from the raids that working class Angelinos are enduring. On the other hand, there are the cynics — a group that, despite my best efforts, I sometimes find myself identifying with — and they are asking if protesting makes any difference at all

“Inside the soul of this accountant who loves his job and loves his wife and loves his son, is this dancer,” Hiddleston said during a press conference. “And that might be true of anyone you know or anyone you see on the street … Inside that human being is greater breadth and depth and range than we could possibly imagine.”

L’Arche challenges the notion that a group home is predominantly a place to provide care services. We have learned over time that the health of our community is rooted in how we gather, celebrate, and make known the unique gifts of every person. This does not diminish the work of competent caregiving, but rather, it places it in a larger context that recognizes how ritual and gathering emphasize a person’s gifts and beauty rather than their diagnoses.

It would be impossible for me to overstate the profound impact that Brueggemann had on justice-oriented Christians. Not only did he write more than 100 influential books of theology and biblical criticism over the course of his long career, he also wrote dozens of articles for Sojourners. There are very few theologians I can think of who taught me as much as Brueggemann did about how to read the Bible and what a deepened understanding of scripture reveals about God’s heart for justice and our ability to imagine a world beyond empire.

Kendrick Lamar is a prophet — and a multimillionaire. Through his music, he tells the stories of the oppressed and marginalized, even as his own net worth surpasses $140 million. He calls for spiritual and political resistance to empire yet stood center stage at the Super Bowl halftime show — America’s most-watched spectacle of capitalist excess. At the end of it, he delivered a moment of rebellion, urging viewers to “turn the TV off,” subverting the very platform that elevated him. And yet, the performance also propelled his music sales and deepened his entrenchment within the industry’s elite. At a sold-out Pop Out show, he brought together feuding Bloods and Crips in a powerful gesture of peace and unity — sponsored, ironically, by Amazon, a corporation widely criticized for its union-busting, exploitative labor practices, and surveillance capitalism.

Leckey's lyrics are soaked in Catholic tradition. When writing songs on Hell Gate, Leckey asked herself: “What if I just full-send it with the Catholic terminology and imagery and tradition, and just do my own thing with it? I think of it as a reclamation and a repurposing.”

Walter Brueggemann believed the future was unwritten. The biblical scholar and theologian, who died on June 5 at the age of 92, spent his remarkably prolific career urging Christians to think beyond what is and imagine what could be. That possibility, he believed, was grounded in the hope of a God who desires justice for the marginalized. Brueggemann had a humble spirit, an academic mind, and a poetic soul — but don’t be fooled: He was, above all, a radical

Walking down a road paved with churches, I approach a large building whose bright orange awning beckons me from down the block. The establishment, Sea Town Fish & Meat Market, is staffed by neighborly workers who call me bebecita when I ask them to weigh my tilapia and salmon. I am there on yet another Friday morning to pick up fresh fish for one of my Lenten devotions: eating fish on Fridays.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday backed a bid by an arm of a Catholic diocese in Wisconsin for a religious exemption from the state's unemployment insurance tax in the latest ruling in which the justices took an expansive view of religious rights.

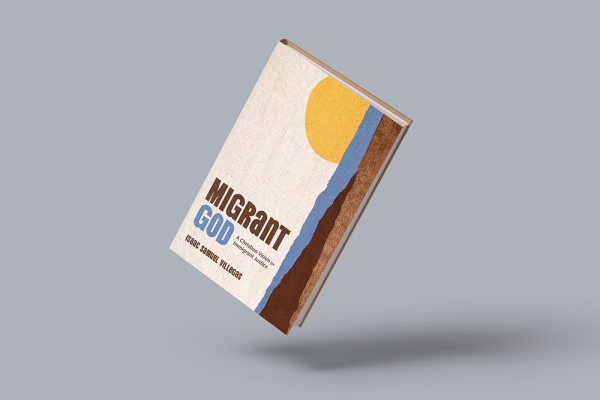

Isaac Villegas' evocative book opens in the Southwest desert along the borderlands of the U.S. and Mexico as a group of people leave crosses in the places where migrants have lost their lives. These crosses, writes Villegas, are “...an act of devotion to a stranger who should have been our neighbor… Each crucifix remembers a life lost to the violence of immigration policies.