Sometimes I am haunted by Glennon Doyle’s forward to the late Rachel Held Evans’ book Searching for Sunday. Doyle begins: “Whenever I want to scare myself, I consider what would happen to the world if Rachel Held Evans stopped writing.” In 2019, about four years after those words were published, Evans died. She was 37, survived by her husband, two kids, and Christians around the world who found comfort in her faith-rooted advocacy for racial justice, LGBTQ+ rights, and egalitarianism.

Just a short walk from my home near Princeton University, students, faculty, staff, and community members have come together to demand the university divest from financial and military support of the state of Israel and release a public statement calling for a ceasefire in Gaza — one of many similar protests that have been happening at college campuses across the U.S. over the past two weeks. Stroll by the encampment at any given time, and you’ll see folks of all ages and races gathered together on blankets and tarps sharing crowdfunded hot meals as scholars address the group; kids play and others offer physical and spiritual care, or clean up the encampment grounds. You might hear community announcements, prayer, music, or, at times, chants like “disclose, divest / we will not stop / we will not rest.”

My “For You” page is dancing again. Coming off the release of Beyoncé’s country album, Cowboy Carter, the TikTokers have taken center screen and are imitating line dances in celebration of her new sound. Sheepishly, I have been attempting to join in. I don’t dance. Or I should say I do not dance well. I’ve never been classically trained, I’ve got two left feet, and I still have to silently mutter the steps to the electric slide to stay on beat. I’ve consistently struggled to find my rhythm, but I dance anyway.

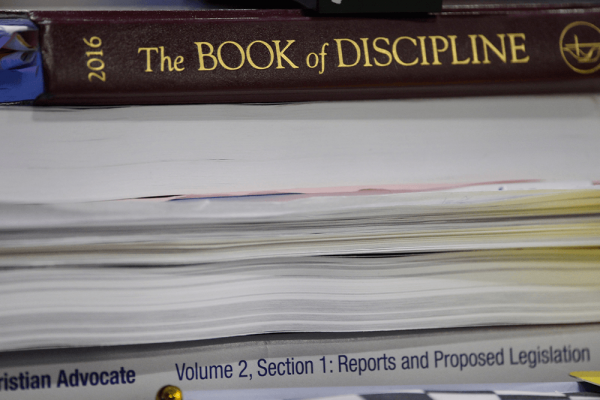

The United Methodist Church voted this week to approve a petition affirming a right to abortion and pledging “solidarity with those who seek reproductive health care.” The vote was part of the UMC’s 2020 General Conference, which was delayed until 2024 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 1985, Chicago Mayor Harold Washington passed an ordinance prohibiting city workers from cooperating with immigration police to detain and deport undocumented migrants. With this ordinance, Chicago became a sanctuary city, joining other U.S. cities in resisting policies that criminalize migration. Almost 40 years later, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott has used Chicago’s sanctuary status as an excuse to bus and fly thousands of migrants to the city from Texas, where he has instituted strict migration policies.

Since Texas began bussing and flying migrants to Chicago in 2022, the city has welcomed over 30,000 migrants. These migrants have endured terribly cold winters, undignified housing, and a city divided by feelings of frustration, indifference, and solidarity.

United Methodist Church delegates voted on May 1 to remove a ban on ordaining gay clergy and to allow LGBTQ+ weddings.

The waiting room of a fertility clinic was one of the most sacred places Elizabeth Wanczak had ever experienced. Most of the people sitting around her had weathered trauma and grief like hers — stories of repeated miscarriage, medical catastrophe, and what felt like endless longing for a baby that had not yet come. And yet, she said, the presence of these people in the waiting room signaled hope. They had not yet given up.

Only 1 in 4 adults play sports each year, according to a 2015 study from NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. This is despite nearly three in four respondents reporting playing as kids, and a majority of adults saying sports improved their mental and physical health ... Ashley Lynn Hengst sees opportunities for the church to help decrease those disparities and build space for more people of all ages to play sports. Hengst serves in pastoral care at All Saints Church in Pasadena, Calif., after a decade working for the Y in youth development.

Eco-chaplaincy, unlike other forms of chaplaincy, is more deeply grounded in humanity’s relationship with nature than a particular religion.

When I say “Christian unity,” what I mean isn’t “Christians should all just agree” or even “Christians should ignore our real differences in doctrine and tradition.” Instead, what I mean by “Christian unity” is that when we center our shared identity in Christ — notwithstanding our differences — we can generate trust and build relationships that bear real fruit, increasing cooperation within the church to address challenges in the world. And I say this knowing that there are often many good reasons why Christians are not unified, including differing views on issues that cut to the heart of our faith, such as our interpretation of scripture, what we believe about the role of baptism, and vastly different governance structures, as well as differing views around contentious issues such as abortion and sexuality. But Christian unity is still worth pursuing because it ultimately strengthens our collective witness, advancing the love of God and work of justice.