Brian D. McLaren is a best-selling author, speaker, activist and networker among innovative faith leaders. A former pastor, he has written 15 books, including The Great Spiritual Migration. He is an Auburn Senior Fellow, living in Florida.

Posts By This Author

‘They've Gerrymandered the Bible and the Constitution’

One of the things that makes America a can-do nation of innovation is that we find ways to work together, using our disagreements and diversity as an asset. Because we don’t swallow the status quo and bow down in reverence to group-think, we have been able to land on the moon, cure cancers, and invent the internet.

From the Archives: March 2004

Consider the Turtles

PEOPLE WHO are sensitive to creation know that creation is in constant flux. Continents drift, climates change, magnetic poles flip-flop, and bogs gradually give way to wet meadows and then various kinds of forests. There’s a natural succession out here under the sun, and I think there’s a kind of natural succession going on theologically for many Christians as well. ...

First, increased concern for the poor and oppressed leads to increased concern for all of creation. The same forces that hurt widows and orphans, minorities and women, children and the elderly also hurt the songbirds and trout, the ferns and old growth forests: greed, impatience, selfishness, arrogance, hurry, anger, competition, irreverence—plus a spirituality that cares for souls but neglects bodies, that prepares for eternity in heaven but abandons history on earth. ...

A Theology of Life and Death

A Palestinian Theology of Liberation: The Bible, Justice, and the Palestine-Israel Conflict, by Naim Stifan Ateek. Orbis.

SOME YEARS AGO, I convened a trip to the so-called Holy Land. It was not a trip about “walking where Jesus walked,” although we did a lot of that. It was a trip to discover facts on the ground in the Israel-Palestine conflict and to meet Jewish, Muslim, and Christian peacemakers in the region. Our band of 20 or so was led by organizers Jeff and Janet Wright, passionate Christians who love the land and all its people.

Nearly everyone on the trip had a breakdown moment, when the tragedy of Israel-Palestine overwhelmed them. My wife, Grace, described a sudden feeling that she had spent her whole life in a totalitarian regime and that “what I thought of as news had really been propaganda all along.” The reality of Israel-Palestine was so different from what she had heard both in the Christian community and in the mass media that she was deeply shaken. We all felt that our trip had exposed so much of the so-called news we had heard from Israel-Palestine as prejudiced, one-sided, and intended to conceal more than reveal.

A trip highlight was a visit to the offices of Sabeel, the headquarters of Palestinian liberation theology, and a meeting with its founder Naim Ateek, a theological hero I’d admired from afar. What Desmond Tutu is to South African theology and Martin Luther King Jr. and James Cone are to North American black theology, Ateek is to Palestinian and Middle Eastern theology. I have since been honored to be an ally in the important work of Sabeel.

Ateek has written a definitive introduction to his work. A Palestinian Theology of Liberation will be especially helpful to three groups of people in the U.S.

Florida Prosecutor’s Moral Case for Renouncing the Death Penalty

Indeed, a comprehensive analysis of deterrence studies by the National Academy of Sciences found no evidence that the death penalty impacts murder rates in either direction. Ayala emphasized that her office pursues evidence-based practices, not policies such as the death penalty whose deterrent effect rests on faith alone.

Faith in a Glass of Water

Each of us has one hundred times as many water molecules in our bodies than the sum of all other molecules combined. Today is World Water Day, a good day to reflect on how this symbol that blesses, sanctifies, and purifies in our rituals, but too often, does not do the same in daily life.

7 Ways to Live a Faithful Life

“And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.” [Micah 6:8]

Too often, perversions of our world’s religious traditions make the daily news for their violence, corruption, greed, and prejudice. Meanwhile, authentic representatives of those traditions are often busy doing good — good that goes largely unnoticed. That’s why I’m glad that a diverse group of religious leaders are sharing about seven ways authentic people of faith can work together to make a better world.

I served as a progressive evangelical pastor for 24 years, and during those years, I saw the evangelical movement struggling with its identity. The best versions of evangelicalism, whether they were labeled conservative or progressive, always took seriously passages like Matthew 25, where Jesus said, “For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink.” Those verses continue to inspire evangelicals of all persuasions to engage in life-giving mission — and in particular, to engage constructively in the world in seven positive, reconciling, and healing ways.

If you invest just a few minutes over the next seven days thinking and speaking up about these seven ways to participate in our world, I believe by week’s end you will be moved to action and in it find a richer, more faithful life:

An Open Letter to Publix

Dear Publix Leadership,

I should begin by saying that I am in almost all ways a big fan of your company. I often shop in a nearby Publix, and shopping there truly is a pleasure. It is clean. The staff are friendly and helpful. The products are good and the prices reasonable.

I'm especially impressed with the way Publix hires people with disabilities.

To provide a needed service and then go above and beyond in seeking to benefit the community — that's a winning combination, and a legacy to be proud of.

That's why I've been so surprised to see Publix (along with Wendy's) refusing (so far) to join the Fair Food Program. And that's why I've been outspoken in my desire to see Publix live up to the ideals of its founder, George Jenkins, who said, “Don’t let making a profit stand in the way of doing the right thing."

Brian McLaren responds

First, thanks to Peg Conway, Bob Blackburn, and others who voiced their concern about how I represented the Pharisees in my article on hell.

Beyond Fire and Brimstone

Jesus' teaching about hell flipped popular imagery of the afterlife upside down—and offered a radical, transformative vision of God.

MANY PEOPLE HAVE been given a very tame and uninteresting version of Jesus. He was a nice, quiet, gentle, perhaps somewhat fragile guy on whose lap children liked to sit. He walked around in flowing robes in pastel colors, freshly washed and pressed, holding a small sheep in one arm and raising the other as if hailing a taxi. Or he was like an “x” or “n”—an abstract part of a mathematical equation, not important primarily because of what he said or how he lived, but only because he filled a role in a cosmic calculus of damnation and forgiveness.

The real Jesus was far more complex and interesting than any of these caricatures. And nowhere was he more defiant, subversive, courageous, and creative than when he took the language of fire and brimstone from his greatest critics and used it for a very different purpose.

The idea of hell entered Jewish thought rather late. In Jesus’ day, as in our own, more traditional Jews—especially those of the Sadducee party—had little to say about the afterlife, about miracles, about angels and the like. Their focus was on this life and on how to be good, just, and successful human beings within it. More liberal Jews—especially of the Pharisee party—had welcomed ideas on the afterlife from neighboring cultures and religions, especially the Persians.

To the north and east in Mesopotamia, people believed that the souls of the dead migrated to an underworld whose geography resembled an ancient walled city. Good and evil, high-born and lowly, all descended to this shadowy, scary, dark, inescapable realm. For the Egyptians to the south, the newly departed faced a ritual trial of judgment. Bad people who failed the test were then devoured by a crocodile-headed deity, and good people who passed the test settled in the land beyond the sunset.

'12 Years a Slave:' A Film of Moral Gravity

I pre-screened 12 Years a Slave the same weekend I saw Gravity. The two films couldn’t be more different, although they do have some fascinating (if not immediately obvious) commonalities.

As for commonalities, they’re both powerful and both deserve to be seen. Both are about people trying to get home — one, in a harrowing adventure that takes several hours, the other in an agonizing 12-year struggle. The protagonists of both movies demonstrate heroic resilience and courage. One struggles with physical weightlessness, the other with a kind of social or political weightlessness.

Although Gravity impressed and fascinated me, 12 Years a Slave affected me and shook me up. Now, several days later, scenes from the film keep sneaking up on me and replaying in my imagination — three in particular.

Trayvon and George: A Tale of Two Americas

The recent “not guilty” verdict out of Sanford, FL, reflects the principle of the American legal system that if there is reasonable doubt, courts will err on the side of innocence. I dispute neither the principle nor the decision by the jury. But that doesn't leave me satisfied about the outcome.

Jesus said that true justice exceeds that of “the scribes and Pharisees” — and the same could be said of the prosecution and defense. Legal justice seeks only to assign guilt or innocence. Holistic justice works for the life, liberty, and well-being of all. And it especially works for reconciliation between the two Americas that can be identified by their reaction to the case.

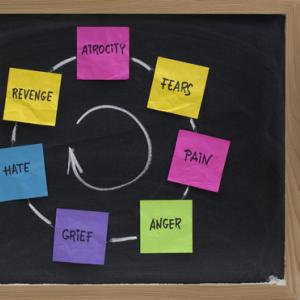

Here We Go Again?

Joe Scarborough said what a lot of Americans are thinking as they watch anti-American protests and embassy attacks in many places across the Muslim world.

"You know why they hate us? They hate us because of their religion, they hate us because of their culture, and they hate us because of peer pressure," Scarborough said on the MSNBC program "Mornin Joe" on Sept. 17.

"And you talk to any intelligence person, they will tell you that's the same thing, and all those people who think we're going to go over there and change them are just naive. ... They hate us because of waterboarding? No they don't. They hate us because they hate us. They hate us because of Obama's drone attacks? No they don't. They hate us because they hate us."

Now Joe would be the first to admit that “they hate us because they hate us” is ... somewhat lacking in analytical depth. But it’s even worse than that. It is a foolish step down an oil-slick slope into a deep, old rut that runs in a vicious, dangerous circle.

What Kind of Exceptionalism Is Worth Desiring in America?

Photo via Alex Pix / Shutterstock

What does it mean to be exceptional?

Most people have to worry about making enemies. You know, they’re constantly freaked out that they might offend somebody or hurt somebody’s precious feelings. But I don’t worry about that. I’m exceptional. Other people in my family worry about everyone getting their fair share at the dinner table. They might really like mashed potatoes or lasagna, but they only take a normal small portion so that their sister or grandmother or cousin can have some too. But I don’t worry about those sorts of things. After all, I’m exceptional. I take as much as I want.

When you’re an exceptional nation, you want other nations to worry about your opinion of them. You don’t really care what their opinion is of you. When you’re a run-of-the-mill country, you’ll be nervous about going against the United Nations or the Geneva Conventions or the International Criminal Court and such, but when you’re an exceptional country, that sort of concern is beneath your dignity. You set expectations; you don’t fulfill them. Of course, with exceptional status comes exceptional responsibility, so we have the sole responsibility to drop nuclear bombs on nations that cause problems for the world—unexceptional nations, that is, which means everybody else but us. It’s a tough job, being exceptional, but somebody has to do it.

Between now and the elections in November, my guess is we’re going to hear the term “American exceptionalism” echoing from the mountains to the prairies to the oceans white with foam; echoing ad nauseum. It’s become a powerful political meme in recent years, popular but poorly defined. The history of the term aids and abets in its vagueness.

Thomas Jefferson repeatedly spoke of the United States as a unique—or exceptional—historical phenomenon. As a democratic republic, it differed from Europe, and all the nations of the past. Since then, of course, scores of nations have followed our example in forming democratic republics, so what was exceptional in Jefferson’s time has now, we might say, become the norm.

Does that make us “the nation formerly known as exceptional,” but now typical?

We're Connected by What We Eat

To the farmers who grow our food, the harvesters who pick it, the transporters who bring it to market, the grocers who present it, and the cooks who prepare it.

To the farmers who grow our food, the harvesters who pick it, the transporters who bring it to market, the grocers who present it, and the cooks who prepare it.

Here's the prayer we prayed at a nearby Publix grocery in the produce section on Friday:

A Prayer for Publix

Living God, you are the Creator of this beautiful and fertile world. You made sun, rain, soil, air, seed, and seasons. We praise you for the green of lettuce, the yellow of lemon, the orange of a tangerine, and especially for the bright red of a tomato. They are beautiful to our eyes, delicious to our taste buds, and nourishing to our bodies. We pray to the Lord, Lord, hear our prayer.