Commentary

AS FIGHTS ABOUT the budget and other economic issues are again riveting the nation’s capital, the rest of the country yawns. Possible government shutdowns, threats to default on our nation’s debt, and proposals to decimate food assistance for struggling Americans seem to be business as usual in Washington, D.C. These budget battles have become so frequent that it is tempting to dismiss it all as political posturing. But that would be a mistake.

The biggest challenge facing Congress should be a non-issue. The debt ceiling is simply the amount of debt the U.S. is legally allowed to hold. It is about paying off the bills that Congress has already incurred from past appropriations—not about giving permission for new government spending, as many people falsely assume. Congress has raised it nearly 100 times since the end of World War II, but it only recently became a political football. Because the consequences of not raising the debt ceiling and defaulting on our nation’s obligations could be catastrophic, some leaders have tried to leverage it for political gain. After the country came close enough to a default in 2011 to receive a credit downgrade, President Obama has responsibly refused to negotiate over raising it. His assumption is that GOP leaders in Congress wouldn’t throw the economy off the cliff for their own political gain. The American people are left watching this game of chicken and hoping somebody blinks.

While this is clearly a partisan game, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The U.S. has always honored its debts. Should the country default, the market turmoil and long-term effects could be catastrophic for the global economy. Domestically, it could throw the U.S. back into recession.

IN 1988, a bronze sculpture of Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd’s knotted gun was placed outside the United Nations headquarters in New York. As Kofi Annan, former U.N. secretary general and Nobel Peace laureate, remarked at its unveiling, the sculpture isn’t just a cherished piece of art, but a powerful symbol that encapsulates in a few simple curves the greatest prayer of humanity: not for victory, but for peace.

Inside the U.N. building is a mosaic representing all the nations of the Earth, accompanied by Jesus’ words, “Do unto others what you would have others do unto you.” For many seasoned peace campaigners, myself included, this prayer was partly answered when the 193-nation U.N. General Assembly overwhelmingly approved the Arms Trade Treaty in April.

The treaty seeks to regulate the international trade in conventional arms, from small arms to tanks, combat aircraft, and warships. It aims to foster peace and security by putting a stop to the destabilizing flow of arms to conflict regions. This process cannot, however, be only a matter of negotiation and numbers. What needs to undergird the treaty is protecting humans, made in God’s image. What needs to motivate the treaty is ensuring the possibility of what philosopher Hans Jonas called “the permanence of an authentically human life on Earth.”

The statistics are frightening. Globally, one person dies every minute from armed violence. This treaty will help halt the uncontrolled flow of arms and ammunition that fuels wars, atrocities, and rights abuses. The devastating humanitarian consequences of the two-year war in Syria, a war fueled in part by the irresponsible export of arms, underline just how urgently this treaty is needed.

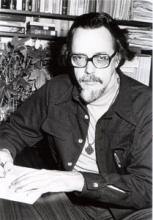

JOHN HOWARD YODER, who died in 1997, was a theological educator, ethicist, historian, and biblical scholar. He is best known for his 1972 masterpiece The Politics of Jesus, his radical Christian pacifism, his influence on theological giants such as Stanley Hauerwas, and his advocacy of Anabaptist perspectives within the Mennonite community and beyond. Many testify that Yoder’s exposition of the gospel allowed them to grasp radically good news in the life and teaching of Jesus Christ.

There is a dark cloud over Yoder’s legacy, however, that refuses to dissipate. Survivors of Yoder’s sexual abuse and other advocates have renewed their calls for the Mennonite Church, including Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary (AMBS), to revisit unfinished business with his legacy.

On Aug. 19, the executive director of Mennonite Church USA, Ervin Stutzman, announced the formation of “a discernment group to guide a process that we hope will contribute to healing for victims of John Howard Yoder’s abuse as well as others deeply hurt by his harmful behavior. We hope this work will lead to church-wide resolve to enter into lament, repentance, and restoration for victims of sexual abuse by other perpetrators as well.”

IT CAME TO pass in the summer of ’72 that many young people gathered in Dallas for Explo, a week of training for Christian witness sponsored by Campus Crusade for Christ. ... And among those present in Dallas were some messengers of peace—some post-Americans calling themselves the People’s Christian Coalition, and a few sons of Menno sent by the Mennonite Central Committee, who had also come to witness for their Lord.

The messengers of peace set up their booths along with many others and distributed their literature. And many people came by. Some looked and smiled; some looked and frowned. Some said “right on” and “we need that” in response to posters saying “blessed are the peacemakers” and “swords into plowshares”; but others said “praise the Lord, God will take care of wars, all we need is to win people to Christ.”

THE PHRASE “a revolution of rising expectations” is now part of the social science literature. When people who are not oppressed have a belief that life is getting better as economies improve, their expectations often outstrip the pace of actual change. Those rising expectations lead to unrest as demands for improvement continue to grow.

This summer we have seen that play out in several countries. As living standards increase, people are less likely to tolerate corrupt and inefficient governments. Washington Post reporters Anthony Faiola and Paula Moura recently wrote, “One small incident has ignited the fuse in societies that, linked by social media and years of improved living standards across the developing world, are now demanding more from their democracies and governments.”

In Turkey, it was the government’s plans to destroy the only public green space in the heart of Istanbul, a park that was to be replaced with a shopping mall. Protests against the plan soon grew into broader concerns about what is seen as increasingly authoritarian rule by Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. They turned violent when peaceful demonstrators were attacked by police, and ultimately an Istanbul court ruled against the plan, although it is not finally settled.

In Brazil, protests that began over a proposed rise in bus fares brought hundreds of thousands of people into the streets. The protests soon escalated into opposition to the large amounts of money the government is investing in facilities for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics, while neglecting basic health care and education. President Dilma Rousseff has promised political reforms and increased spending on public transportation and other social needs.

TORU HASHIMOTO, the mayor of Osaka and co-leader of the Japanese Restoration Party, has been known for his provocative statements. In May, while speaking with reporters on Japanese wartime behavior, he endorsed rape and sexual enslavement, saying, “When soldiers are risking their lives by running through storms of bullets, and you want to give these emotionally charged soldiers a rest somewhere, it’s clear that you need a comfort-women system.” These comments drew international condemnation, but they also revealed the all-too-familiar interlocking of sexism, militarism, and sexual violence. Far too often, the idea of a greater “noble cause” is used to justify the sacrifice of women to a military sexual slavery system.

During World War II, historians estimate that 100,000 to 200,000 Korean women and girls, ages 11 to 30, along with women and girls from China, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Taiwan, were kidnapped or falsely promised jobs and taken to various locations to serve as “comfort women”—the euphemism for sexual slaves. They “served” an average of 30 to 40 soldiers a day and suffered through beatings, venereal disease, forced abortions, mental anguish, and often death. At the end of the war, these women and girls were killed, forced into suicide, or abandoned. Of the few who were able to return to their homeland, many suffered social alienation, humiliation, poverty, STDs, and endless mental anguish.

The Japanese government had largely denied the existence of Japanese military sexual slavery until 20 years ago, when it offered a statement of apology. The apology was seen as empty by many people, as Japanese politicians and revisionist historians not only reneged on the apology but sought to omit the tragedy from the telling of Japanese history. In response, surviving Korean “comfort women” or halmulni (a term of endearment and respect meaning grandmother) have gathered every Wednesday since 1992 in front of the Japanese embassy in Seoul as a reminder that they demand to be seen, heard, and offered a genuine apology.

THOSE WHO BELIEVE in freedom and work for justice in our world sometimes grow nostalgic about the 1960s in this country, looking back at the leadership that emerged from African-American churches in the South, drawing allies from outside the region and beyond the bounds of creed. America has a vivid, living memory of faith inspiring public justice. But the civil rights movement did not just happen. The March on Washington and Selma were moments in history made possible by movements that grew out of hard work over the course of decades.

This summer in North Carolina, “Moral Mondays” at the state General Assembly have drawn thousands of weekly protesters, more than 800 of whom have been arrested for engaging in mass civil disobedience. A few weeks into the campaign, some elders started saying it felt like the ’60s all over again. The Washington Post highlighted NAACP state chapter president Rev. William Barber’s dynamic preaching. The New York Times pointed to the significance of hundreds of clergy uniting to lead the movement. MSNBC andFox News set up their satellite trucks. Week after week, thousands of people kept coming.

When reporters asked why, participants explained the concerns: 500,000 people denied health care when the legislature refused federal funds for Medicaid expansion, 70,000 people whose unemployment insurance was cut off, thousands of poor families denied an earned income tax credit, wholesale repeal of the hard-won Racial Justice Act, and diversion of public education funds through a voucher program. The reasons were legion, but they were not, by and large, unique to North Carolina. They were the sort of changes the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) promotes at the state level throughout the country. How, then, did this grassroots resistance movement emerge in North Carolina?

ON MARCH 1, 1954, at 6:45 a.m., the U.S. government detonated a 15-megaton hydrogen bomb in the Bikini Atoll. Within a few hours, the ash-like radioactive fallout from the “Bravo” test explosion began to descend on the nearby inhabited atolls of Rongelap and Rongerik. An Air Force witness said the fallout resembled “a snowstorm in the middle of the Pacific.”

A two-inch-deep layer of radioactive dust accumulated on Rongelap, contaminating its food supply and drinking water. Children playing in the powder experienced skin eruptions on their arms and faces. By the end of the day, the residents of Rongelap had begun to exhibit the symptoms of acute radiation exposure: burns, severe vomiting, diarrhea, and hair loss.

THE UNITED STATES has more than 2.3 million prisoners, a higher number than any other country. How did we become the world’s leading jailer? One of the main culprits: Mandatory sentences.

Visiting those in prison and giving Christmas gifts to children of incarcerated parents are only two steps toward fulfilling Jesus’ command to care for the “least of these” (Matthew 25). It’s time for the church to get serious about criminal sentencing reform—particularly, the reform of mandatory minimum sentencing laws, which lock up so many people for so long with so little benefit to society.

The explosion in state and federal prison populations and costs began in the 1980s with the so-called war on drugs. Lengthy mandatory minimum prison sentences passed by lawmakers are the primary weapon in that “war.” Judges have no choice but to apply these automatic, non-negotiable sentences of five, 10, or 20 years or even life in prison without parole. Whether the punishment actually fits the crime or the offender, protects the public, or leads to rehabilitation is irrelevant.

The results are unsurprising: irrational sentences, $80 billion annually in prison costs, and horrifically overcrowded prisons. States as varied as Georgia, New York, Delaware, South Carolina, California, and Michigan have confronted the reality of unsustainable prison budgets by repealing mandatory minimum sentences or creating “safety valve” exceptions that let judges go below the mandated punishment if the facts and circumstances warrant it. During this wave of reforms, crime has dropped to historic lows.

THE APRIL 24 collapse of a garment factory near Dhaka, Bangladesh, killed more than 1,125 people. That tragedy followed a fire that killed 112 last November at a factory making goods for companies including Walmart. According to the International Labor Rights Forum, at least 1,800 garment workers in Bangladesh have died in fires or other factory disasters since 2005. The collapse near Dhaka is the largest disaster in that time and the one that has gotten global attention.

As a Dominican Catholic sister and member of Catholic Scholars for Worker Justice, I approach reflection on such a disaster from the foundation of Catholic social teaching. Each of the social principles below relates to the situation in Bangladesh and challenges us to reflect on our own regard for those who provide our clothing.

- Life and dignity of the human person. Story after story of the people who work in the garment industry shows the lack of respect for workers. Long hours, few to no breaks, prevalent verbal, physical, and sexual abuse, and now the collapse of a factory—do we need any more proof that human life is held in so little regard? Many years ago, Cardinal Joseph Bernardin called for an understanding of “respect life” as inclusive of human life “from womb to tomb.” Our upholding of life must include working toward changing factory conditions so that a debacle such as Dhaka never happens again.

PUBLIC PRESSURE IS finally building on President Obama to fulfill his promise to close the Guantanamo prison, which still houses 166 miserable leftovers from the Bush-Cheney “war on terror.” That pressure is well-placed. Gitmo has been a disaster from the beginning. Christians and other people of faith must join in calling for its closure.

Detainees were originally shipped to Gitmo in the vain hope of avoiding the reach of the U.S. judiciary. In this sense Gitmo was conceived in Constitution-evading sin. The Supreme Court rejected the evasion in 2006, but the damage was already done.

Some of the detainees brought to Gitmo were tortured. This has been confirmed by numerous sources, including a leaked 2006 Red Cross report and the 577-page report of a bipartisan blue-ribbon detainee panel organized by The Constitution Project, on which I served.

More than half of the remaining detainees have been cleared for release, but for domestic and geopolitical reasons they continue to be held. More than 100 of them are currently on a hunger strike, with dozens being force-fed, a practice that violates both American Medical Association and World Medical Association standards and which our Detainee Task Force condemned unequivocally.

Some detainees cannot be tried because the evidence against them was obtained by brutal or torturous means and is tainted or would be embarrassing to the U.S. Others are slated for trials in novel military commissions whose legal problems are so severe that they have not proceeded. Civilian trials on U.S. soil were blocked in 2009 by a fearful, recalcitrant Congress. So 166 men are held in limbo indefinitely, without trial and without foreseeable prospect of release. This is unconstitutional and a violation of the most basic legal and human rights.

THE FUNCTION of healthy religion and church is to provide individuals and society with a collective container that carries the objective truth of reality for individuals. The Great Truth is too grand and transcultural to be entrusted to the vagaries of individuals and epochs. Otherwise, society becomes a massive runway for unidentifiable flying objects—each claiming absolute validity and turning their subjectivity into the only sacred.

The ground for a common civilization and shared values is destroyed if our religious experience is basically unshareable or without coherent meaning. We end up where we are today: pluralism without purpose, individuation but no community.

BECAUSE I'M A Jew in Bethlehem, Pa., also known as “Christmas City USA,” I spend December celebrating Jesus’ birth. Representations of other religions are largely absent, but with evergreen trees adorning lampposts, the nativity scene at city hall, and 6-foot-high electric Advent candles, Christmas here is both beautiful and unavoidable.

Given Christianity’s dominance in the United States, similar examples extend into other seasons and across the country. Christian holidays and Sunday receive scheduling deference, Christian worship options are varied and plentiful, and debates over public “religion” focus almost entirely on Christianity. In contrast, Jews use vacation days to observe holidays, Jewish religious communities are far fewer, and there is no movement advocating Jewish prayer in schools.

Even in interreligious settings intended to be neutral, Christianity retains primacy. Exchanges emphasize concepts in Christianity, such as belief and faith, and downplay the Jewish stress on action, behavior, and ritual. When interfaith interactions turn to biblical texts, they rely on Christian hermeneutical approaches such as using English translations without acknowledgment of their underlying Hebrew and eschewing the Jewish practice of viewing the Bible through subsequent commentaries. To me, these verses look discomfortingly naked when not swaddled with sages’ centuries-old wisdom, and Christian translations often conflict with how I understand the original language.

EVERY TIME I fly into Ontario, Calif., I see neat blocks of gleaming, low-rise warehouses surrounded by well-manicured trees and shrubbery. I now know that what goes on inside those buildings is not nearly so pretty.

As a board member of People of Faith United for Worker Justice, a local faith-rooted worker justice organization, I have seen the dismal working conditions inside several of these warehouses and have heard the testimonies of workers who have been seriously injured on the job. Eighty-five percent of the warehouse workers in Southern California earn minimum wage and receive no health benefits, even though their jobs entail unloading and reloading heavy boxes.

Since many of these workers are hired through temp agencies, which are often located inside the warehouses, workers’ rights are routinely abused. When someone is injured, instead of being cared for, he or she is simply not called back to work the next day. When workers complain about poor working conditions—such as a lack of breaks, access to bathrooms, or having to lift heavy boxes into freight trucks in 108-degree temperatures—the managers tell them it’s not their responsibility because the workers are employed by the temp agency. The temp agencies in turn claim they are not responsible for conditions in the warehouses because the agencies are separate companies.

PRESSURE IS BUILDING for the United States to become militarily involved in the Syrian civil war. The result would be further bloodshed and destruction for the people of Syria, the worsening of an already grave regional security crisis, and U.S. involvement in another Middle East war.

The Obama administration has apparently decided to provide arms to the rebels. Sen. John McCain and others in Congress are calling for a no-fly zone and air strikes against Syrian government targets. The increased hard line comes in response to allegations that Syrian government forces have used chemical weapons, crossing the “red line” President Obama warned against—although reports have surfaced that rebel forces also may have used chemical weapons.

Concerns about the use of chemical weapons are serious, but they are not a justification for military action that could drag U.S. forces into the deadly civil conflict. Bombing strikes would not be sufficient to neutralize Syria’s vast arsenal of chemical weapons, and they could cause chemical explosions that would release the deadly toxins we seek to contain.

For a military operation to achieve results, it would have to be a large-scale undertaking. Creating a humanitarian safe zone or attempting to impose a no-fly zone would require a major commitment of allied forces and would lead to serious military confrontation with hostile Syrian forces.

COMING TO know Christ can be likened to culture shock, when all the old ego-props are knocked down and the rug pulled out from under one’s feet. A maturing relationship with God involves the pain of continual self-confrontation as well as the joy of self-fulfillment, continual dying and rising again, continual rebirth, the dialectic of judgment and grace. For the first time in my life, I have begun to have the strength to face myself as I am without excuse—but equally important, without guilt. I know that I am sinful, but I could not bear this knowledge if I did not also know that I am accepted.

I now understand the profundity of 1 Corinthians 13, when Paul says that all that ultimately matters is love. Human endeavor without it is a “noisy gong or clanging cymbal.” One may have “prophetic power” (i.e., be a perceptive theologian), “understand all mysteries and all knowledge” (i.e., be an insightful intellectual), “give away” all one has or “deliver” one’s “body to be burned” (i.e., be a dedicated revolutionary), “have all faith, enough to move mountains” (i.e., be an inspiring preacher). But without love these are nothing, absolutely nothing.

YEAR AFTER YEAR, more than 50 percent of the federal discretionary budget goes to the Pentagon, while only one-third of the non-defense discretionary budget is invested in struggling states and communities—a contrast at the heart of this year’s congressional budget battles. And yet for decades the Pentagon budget has remained sacrosanct while local communities suffer.

From the ground up, activists around the country are fighting back. They are striving to save their communities by calling for cuts in what they perceive as a bloated Pentagon budget—starting in some of the most unlikely places: local city councils.

My organization—the Minnesota Arms Spending Alternatives Project (MN ASAP)—is just one of many groups around the country seeking to shift federal spending priorities from preparing for and waging war to meeting local needs. Through a simple resolution, we build political support by asking churches, organizations, city councils, and state legislators to endorse our initiative to cut Pentagon spending and invest in communities.

In 2011, the Minnesota state government shut down over disputes as to how to address a two-year, $5 billion budget shortfall. Yet Minnesota taxpayers spent nearly $3.5 billion to fund the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in 2011 alone, bringing total Minnesota taxpayer spending for these wars to $40 billion, according to the National Priorities Project. As in other states, many cities and communities in Minnesota are managing austerity budgets, tightening their belts and laying off police, firefighters, and teachers—all while the Pentagon budget remains unchecked.

DURING CONGRESS’ current debate about immigration reform, the realities faced by immigrants and border communities are all too often misunderstood and misrepresented. What are the facts about border issues?

Myth #1: Border walls are effective for keeping out unauthorized border crossers.

Reality: History teaches us that walls don’t work when economic opportunity is on the other side—but walls that are higher and longer do cause more injuries and death when people are forced to go over, under, and around.

The most recent era of migration across the southern U.S. border was caused primarily by economic factors, as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) caused millions of Mexican farmers to lose their livelihoods. The current border strategy, enacted hand in hand with NAFTA, envisioned deterring economic refugees by intentionally funneling migration to dangerous desert areas. The danger and death happened; the deterrence didn’t. It was the U.S. economic downturn, much more than the wall, that has caused the current net-zero immigration rate.

IN THE summer of 1969, then-Sen. Gaylord Nelson was on a conservation speaking tour of the West when he visited the beaches of Santa Barbara, at that time despoiled by one of the worst oil spills in U.S. history. The devastation affected him deeply. Later, while reading an article about the teach-ins organized by anti-Vietnam War activists, Nelson asked himself, Why not have a day for a nationwide teach-in on the environment? Thus was born Earth Day 1970.

The original Earth Day was marked by a massive public outpouring of concern for the environment. Earth Day helped spawn new laws such as the Clean Air and Water Acts and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, but it did little to staunch the more serious wounds of our dying planet. ... Much of the activity during the 20th-anniversary celebration of Earth Day this April 22 will focus on individual acts. ... But there is a danger in an overemphasis on personal acts, when the most grievous assaults on the natural world come from corporations and nations whose self-interested policies of acquisitiveness and greed have brought us to the edge of ecological cataclysm.