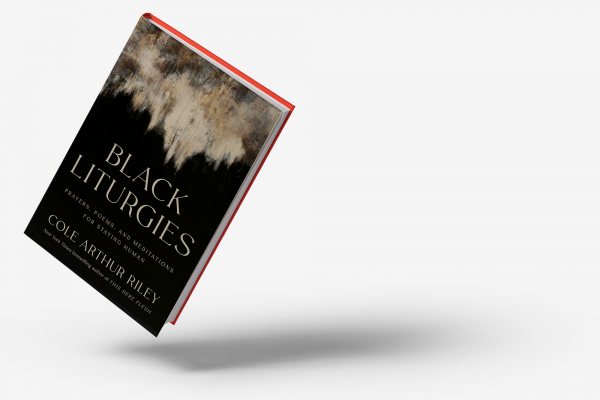

COLE ARTHUR RILEY never wanted to write a prayer book. But when she went looking for liturgical practices that centered Black emotion, Black literature, and Black bodies, she couldn’t find much. Now, for nearly four years, Riley has been curating the Instagram page @blackliturgies, which integrates the truths of dignity, lament, rage, justice, and rest into written prayers. Her new book, Black Liturgies: Prayers, Poems, and Meditations for Staying Human, expands on that work. Typically, prayer books are not page-turners, but once I started reading this one, I couldn’t put it down.

By interpolating corporeal language into her prayers, Riley offers a refreshingly accessible entry into contemplative literature. She has a gentle way of encouraging readers to engage with her prayers. “Turn them over in your hand. Take a deep breath,” she writes. “There is no demand I will make of you, apart from staying near to yourself, your body, your own soul, and the stories that dwell there.”

Read the Full Article