IN HIS FIRST speech as president-elect, Joe Biden outlined four priorities his incoming administration plans to address: systemic racism, the COVID-19 crisis, climate change, and economic hardship and recovery. I am encouraged not just by the breadth of policy detail and ambition in his Build Back Better platform but also by the radically different narrative for the nation and its future. These four pillars should resonate for people across the diversity of the church, and they will require that we generate significant political will, urgency, and accountability within the new administration and Congress to achieve progress on these priorities and more. Along with policy reforms, we also face an imperative to renew our broken and toxic political culture.

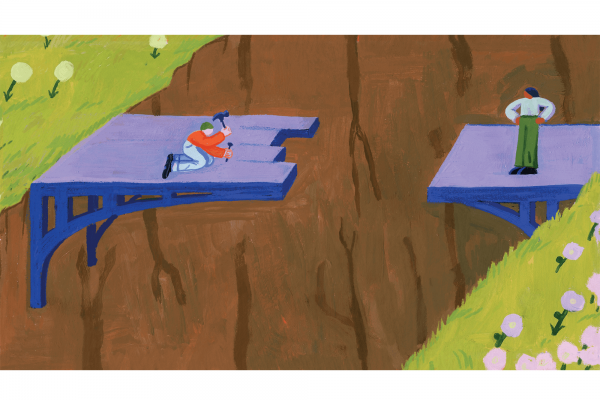

In the gospel of Matthew, Jesus proclaims, “Every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation, and every city or house divided against itself will not stand” (Matthew 12:25). This profound truth is relevant for the church and for the nation.

Read the Full Article