Since the rule of Constantine in the 4th century A.D., church leaders have lived precariously close to showing preference and promoting one political leader over another. The Rev. Billy Graham came to regret his close ties to Richard Nixon, who used "America's Pastor" to his political advantage.

A prophetic distance must be maintained, allowing space between what the Spirit and the Word might say in any given situation, and the political leader or policy in question. The role of prophetic analysis requires distance so as to avoid compromise.

Then, too, we see how important it is not to make our rendition of the Gospel synonymous with a particular view of economics, role of government, social management or civic engagement. After watching Christian leaders running to the beck and call of Nixon, Chuck Colson warned us that the kingdom of Christ does not arrive on Air Force One.

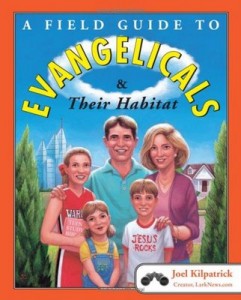

The “E Word” in Christianity is a funny thing.

In one respect, Evangelicals are self-identified, and therefore, self-defined. On the other, popular culture (particularly media) lays its own meaning on what it means to be Evangelical. In the latter context, the word inevitably translates to “Conservative Christian.”

But I think this definition isn’t fair. What’s more, it’s not accurate.

I’m a self-proclaimed “word nerd,” so I tend to turn to etymology for help. The root meaning of “evangelical,” at least as a paraphrase, means “to tell the good news.”

Sufficiently vague, right? Depends on who you ask.

Every so often, evangelicals get the urge to ex-communicate. Feminists, open theists, and universalists have all drawn the ire of their co-religionists. In the absence of a central religious authority, such efforts are doomed to fail.

According to most scholars, evangelicalism is more of a network than a unified church. Magazines, publishing houses, colleges, and parachurch groups play a bigger role than ecclesial bodies. While condemned from many pulpits, the emerging church continues to publish with Zondervan and Baker. Owned by the same company as Zondervan and Fox News (Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation), HarperOne has provided a home for Rob Bell and his Love Wins.

Though it hasn’t been easy, Bell has remained a part of American evangelicalism.

Fried by their battles with fellow believers, some have decided to ex-communicate themselves. Even then it is hard to cut the tie. As in the case of cultural Catholicism, religious terminology may haunt a post-evangelical’s speech. Commenting on this phenomenon, Tony Jones wonders whether evangelicalism is the “new Jewish" — more cultural than confessional.

“Evangelical voters” have now been sized and squeezed into a homogeneous political block. These folks have views on the political right wing, trust in robust American military might, believe that wealth is a blessing to be protected by tax policy, want society to be inhospitable toward gays, oppose any form of abortion, feel that “big” government is always malevolent, and assert that American individualism is the divinely sanctioned cornerstone of the Republic. Apply the label “evangelical” to a voter and you can expect these political responses.

The problem is that it’s simply inaccurate. One size doesn’t fit all when in come to evangelicals. It distorts reality. But that’s just too inconvenient for pundits intent on predicting how various blocks will vote.

Self-identifying as an Evangelical might get me labeled a political activist. Yes, I’m an Evangelical. I’m also a Republican. But touching these two labels together invokes pictures of voting checklist guides, culture wars, and the case of Visine needed to make Michelle Bachmann eyes blink. I‘m not a militant, taking the country back for God.

So am I an Evangelical? Did you know that the family name is actually Swiss-German? That explains our passive-aggressive nature.

The term "Evangelical" is like a pair of hand-me-down underwear. It's been stretched over so many shapes and sizes that it's lost its snap and doesn't fit anyone anymore. It’s been pulled around the circumference of Mars Hill, Seattle and Mars Hill, Grand Rapids. Billy Graham, Ted Haggard, Jim Bakker, Jay Bakker Benny Hinn, Scot McKnight, Don Miller, Jimmy Carter, W., John Piper, Ken Ham, Jim Wallis, and Bill Hybels have all had their turn sporting this hand-me-down garment.

Ask me if I’m an Evangelical and I’ll ask if you know where that label’s been. It’s rubbed against far too much junk for my taste.

Words lose their currency with overuse, it’s true. But it’s also true that a large part of my issue with being labeled an Evangelical is vanity.

I first heard the term "evangelical" in the 1980s, about the time the Swaggarts and Bakkers were imploding. Christianity needed a new name for sane, intellectually sound faith.

"Born-again" had been sullied by the televangelists and worn out by Debbie Boone’s explanation of how she justified singing the lyrics to “You Light Up My Life.”

"Jesus Freak" had died with the Peace movement.

We needed another word to separate true Christians from fake ones; sheep from goats; serious believers from those who merely checked the “Christian” box on their driver’s license application because Jew, Muslim or Ekkankar didn’t apply.

(Sometimes I wonder if all the denominations in Christendom are merely a list of the nomenclature we’ve used to separate Us from Them.)

When I applied for a job at CNN in the 90s, and told the interviewer that I had interned with an evangelical magazine called Christianity Today, his response was, "If it's Christian, it isn't journalism."

Over the years that expanded to, "If it's evangelical, it's Republican. Or Jerry Falwell. Pat Robertson. The Tea Party. Wrapped in a Patriotic Flag. White People. Derivative, cheesy music. Big Money. Big Hair." Fill in the rest of the blanks.

Are those labels a distortion of what it means to be an evangelical? Of course they are. Yet they are how evangelicals are perceived, rightly or wrongly (I personally think it's a mixture of both), in our society.

The reason the word Evangelical has become so poisonous is because the answer to the above question comes from a conversion-based model of cultural engagement - political, theological and social. Too many Christians believe, and have wrongly been taught, that those "others" and "opposites" who have made an active choice not to believe in "our" teachings are justifiably: 1) left to their own devices as we wash our hands of them because of their bad choice (think in terms of blood-on-their-own-head); or 2) uninformed, so much so that their "no" is an illegitimate answer.

Evangelicals care more about positions -- whether progressive or conservative -- than people. We lack nuance. We have become either all Scripture or all Justice. I don't know where the balance was lost in terms of holding Scripture in high authority and, simultaneously, loving with reckless abandon?

Why I’m not an evangelical … and why I am:

“Evangelical” is a dirty word in the New York art world. A friend, an artist, told me that before she understood the claims of the Bible, she thought Christianity was a weird political group, and evangelicals the most extreme and terrifying. Whenever this word is raised, the next statement is “oh no, you are not one of them, are you?!”

Then, I usually say,“well, it depends on what you mean by the word ‘evangelical,’” followed by a confession, “I am not sure if I am an evangelical but let’s do talk about what the word actually means.”

People often assume that I am of the evangelical persuasion because I have been associated with many churches and Christian organizations. I just completed a major project for the 400th Anniversary of King James Bible. I was even appointed by President George W. Bush to the National Council on the Arts. People in the art world assume that if you have anything to do with President Bush and the Bible then you must be an evangelical.

Evangelicals had always seemed like the "other" Christians. They were the ones who didn't celebrate Advent or baptize babies. They were the ones who went colleges that required pledges not to drink, smoke or dance. They were the ones who frowned upon evolution or "free-thinking."

As a child of the 1970s and '80s, I saw evangelicals as politically and socially conservative -- ever skeptical of culture and worried about what we were reading and watching. They bobbed for apples at "Harvest" parties instead of trick-or-treating on Halloween. They were the ones telling Kevin Bacon he couldn't be footloose and fancy free -- or maybe those were "fundamentalists." Did it matter? Was there even a difference?

"There's one thing for sure: 'Evangelical' has become a misrepresented, overly-defined, politicized, theologically kidnapped term. It seems to barely recognize its own creator. What ever happened to true evangelicalism? Whatever happened to that hope of freedom restored?"

Adam Phillips is a Evangelical Covenant Church minister and director of faith mobilization for the ONE Campaign, www.one.org.

This video is the latest installment in an ongoing series at God's Politics where we've asked leading clergy, writers, scholars, artists, activists and others who self-identify as "evangelical" to answer the question, "What is an Evangelical?"

The Christian world is broad and spacious, and within its circumference, like a large bowl holding a variety of colorful fish, swim a surprisingly diverse spectrum of believers. The secular media mistakenly seem to view "the evangelical movement" as a sort of monolithic structure akin to a well fortified garrison ranged to repel the attacks of "liberals" or "progressives" or "mainline churches." Or a right-wing political force often equated with Republicanism.

As the evangelical community in Portland rediscovered the calling of showing, in addition to sharing their faith, everything has changed. And it's only the beginning of what God is doing in our city. We're in it for the long-haul.

Not only have many great needs been met, but churches are working together in relationship as never before. The impact of one church humbly serving is profound. But the impact of a united Church serving in concert, actually has the power to change how the world views the Gospel.

Increasingly, in meetings focused on a wide variety of human tragedies, I hear these words: "What are you doing here? I didn't think evangelicals cared about these things."

I understand those comments. I grew up in a form of Christianity in which "saving souls" was pretty much all that mattered. The God I discovered in that church was a harsh, demanding tyrant; I knew that if I wanted to earn God's love I would have to be very good, follow all the rules, and work very hard. As a devout adolescent I did that. As a young pastor's wife I did that.

Unfortunately, I worked a little too hard and eventually became utterly exhausted, seriously depressed, and physically sick. That plunged me into a total life crisis in which I felt compelled to give up the God of my childhood.

Fortunately, a wise friend said to me, "For a while, forget everything you've ever thought about Christianity; forget the Old Testament; forget Paul and the epistles-and just read Jesus."

So for months -- for years actually -- I just read Jesus. And slowly but surely, Jesus reshaped my understanding of what it meant to be a Christian.

From the Catalyst Conference for evangelical Christian leaders in Atlanta, Sojourners' Director of Mobilizing, Lisa Sharon Harper, gives her answer to, "What is an Evangelical?"

The puzzle here is not that readers of the Bible would tilt toward the political left. That, for me, as well as for thousands of other American evangelicals, is self-evident. Jesus, after all, summoned his followers to be peacemakers, to turn the other cheek, to welcome the stranger and to care for “the least of these.” He also expressed concern for the tiniest sparrow, a sentiment that should find some resonance in our environmental policies.

The puzzle here is not that readers of the Bible would tilt toward the political left. That, for me, as well as for thousands of other American evangelicals, is self-evident. Jesus, after all, summoned his followers to be peacemakers, to turn the other cheek, to welcome the stranger and to care for “the least of these.” He also expressed concern for the tiniest sparrow, a sentiment that should find some resonance in our environmental policies.

No, the real conundrum lies in the subtitle the editors of Christianity Today assigned to Franzen’s article, which was titled, “A Left-Leaning Text.” Adjacent to a picture of a Bible tilted about 45 degrees to the left, the editors added the subtitle: “Survey Surprise: Frequent Bible reading can turn you liberal (in some ways).”

The fact that anyone should register surprise that the Bible points toward the left should be the biggest surprise of all.

Here we go again. Presidential elections are coming and the role of "the evangelicals" is predictably becoming a hot political story.

Ironically, voices on both the right and the left want to describe most or all evangelicals as zealous members of the ultra-conservative political base.

Why? Perhaps because some conservative Republicans want to claim a religious legitimacy and constituency for their ideological agenda, and some liberal writers seem hell-bent on portraying religious people as intellectually-flawed right-wing crazies with dangerous plans for the country.

Let me try to be clear as someone who is part of a faith community that is, once again, being misrepresented, manipulated, and maligned. Most people believe me to be a progressive political voice in America. And I am an evangelical Christian.

I believe in one God, the centrality and Lordship of God's son Jesus Christ, the power of the Holy Spirit, the authority of the scriptures, the saving death of the crucified Christ and his bodily resurrection -- not as a metaphor but a historical event. Yep, the whole nine yards.

Most of my friends knew evangelicalism only through the big, bellicose voices of TV preachers and religio-political activists such as Pat Robertson, the late Jerry Falwell and James Dobson. Not surprisingly, my friends hadn't experienced an evangelicalism that sounded particularly loving, accepting or open-minded.

Most of my friends knew evangelicalism only through the big, bellicose voices of TV preachers and religio-political activists such as Pat Robertson, the late Jerry Falwell and James Dobson. Not surprisingly, my friends hadn't experienced an evangelicalism that sounded particularly loving, accepting or open-minded.

After eschewing the descriptor because I hadn't wanted to be associated with a faith tradition known more for harsh judgmentalism and fearmongering than the revolutionary love and freedom that Jesus taught, I began publicly referring to myself again as an evangelical. By speaking up, I hoped I might help reclaim "evangelical" for what it is supposed to mean.