Sep 18, 2011

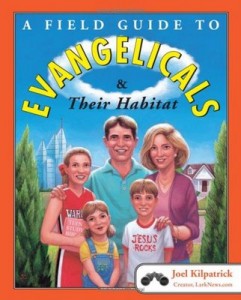

Most of my friends knew evangelicalism only through the big, bellicose voices of TV preachers and religio-political activists such as Pat Robertson, the late Jerry Falwell and James Dobson. Not surprisingly, my friends hadn't experienced an evangelicalism that sounded particularly loving, accepting or open-minded.

Most of my friends knew evangelicalism only through the big, bellicose voices of TV preachers and religio-political activists such as Pat Robertson, the late Jerry Falwell and James Dobson. Not surprisingly, my friends hadn't experienced an evangelicalism that sounded particularly loving, accepting or open-minded.

After eschewing the descriptor because I hadn't wanted to be associated with a faith tradition known more for harsh judgmentalism and fearmongering than the revolutionary love and freedom that Jesus taught, I began publicly referring to myself again as an evangelical. By speaking up, I hoped I might help reclaim "evangelical" for what it is supposed to mean.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login