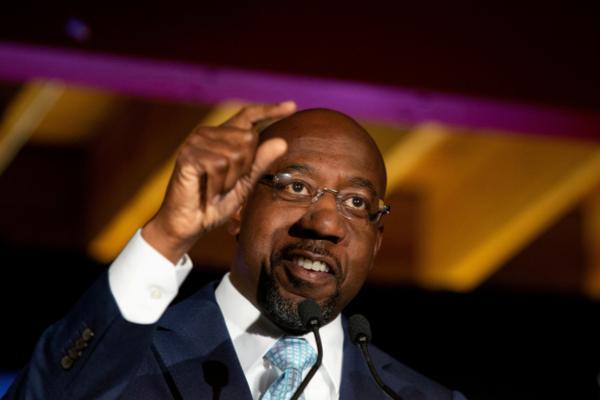

The pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta faces accusations of radicalism, Marxism, and anti-American values. His accusers target his faith, including the sermons he has delivered and who his church has associated with, as the crux of their criticism. These were tactics used to undermine the leadership of Martin Luther King Jr. when he served as a pastor of Ebenezer Baptist in the ’60s — and they’re what Rev. Dr. Raphael Warnock faces today during his campaign for one of Georgia’s seats in the U.S. Senate.

Warnock, who has served as Ebenezer’s senior pastor since 2005, is the Democratic nominee for Georgia’s special election. Kelly Loeffler, the sitting senator who Warnock is running against, has spent or reserved nearly $42 million worth of ad time in the runoff, according to CNN.

Many of her ads characterize Warnock as a dangerous radical; her PAC, Georgians for Kelly Loeffler, launched a website to attack Warnock for a “dangerous agenda,” “radical policies,” and “anti-American values.” The ads say that Warnock “wants to make your neighborhoods less safe,” and claim he “celebrated anti-American hatred.”

Theologians say these attacks are a continuation of racist tactics in U.S. politics and long-held misunderstandings of the Black faith tradition, prophetic tradition, and Black liberation theology.

Rev. Dr. Willie Jennings, professor of systematic theology and Africana studies at Yale Divinity School and author of After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging, said that the critiques against Warnock are an attempt to “take from Black religious figures” what is granted “to white religious figures.”

“White religious figures can be very critical of various aspects of American life or American culture and never be seen as ‘anti-American,’” Jennings said. “Whereas if you’re Black, especially a Black Baptist, and you speak in the prophetic tradition, it’s always interpreted as against the very fabric of America.”

Jennings sees Warnock as standing squarely within the “Black Baptist prophetic tradition” which routinely critiques American imperialism. In his 1967 “Beyond Vietnam” speech offered at Riverside Church in New York City exactly one year before his assassination, Martin Luther King Jr. condemned America’s “failure to make democracy real” and called for his listeners to declare “eternal hostility to poverty, racism, and militarism.”

For Jennings, this posture of critique is essential to the Black Baptist tradition: “While one can participate in American democracy, American life, and the work of a nation, one retains the right to be critical of each and every aspect of that life in this country,” Jennings said. “Nothing is off-limits to criticism, nothing is off-limits to challenge because one understands oneself inside of a more decisive story, that’s the Christian story.”

Liberation theology

The advertisements also highlight Warnock’s defense of Rev. Jeremiah Wright, Warnock’s connection to Black liberation theologian Dr. James Cone, and a visit Fidel Castro made to the church Warnock served at in 1995. Warnock has said that he was not associated with Castro's visit and never met the leader of Cuba during his visit.

Others like Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and Fox News host Tucker Carlson have accused Warnock of being anti-military or racist toward white people. Rubio shared a 26-second clip of a Warnock sermon in which Warnock said “nobody can serve God and the military, you cannot serve God and money.” Carlson, citing Warnock’s work in liberation theology, said there was nothing more racist than asking America to repent of its whiteness.

In both instances the critics mistakenly interpret liberation theology’s critique of American imperialism and white supremacy as an attack on individuals. In responding to Rubio, Warnock said that not serving two masters was a “spiritual lesson that is basic and foundational for people of faith.” (Rubio’s press secretary has not responded to a request for comment.)

“What I was expressing was the fact that, as a person of faith, my ultimate allegiance is to God,” Warnock said in a virtual news conference on Nov. 18. “Therefore whatever else I may commit myself to it has to be built on a spiritual foundation.”

Rev. John Faison, who served eight years in the military and is now senior pastor of Watson Grove Missionary Baptist Church in Tennessee, said he understood exactly what Warnock was saying in the sermon.

“It’s very very simple, you can’t put anything on the same level of allegiance to God,” Faison said. “To make it relative to today, he took the approach of saying money isn’t the only thing we can put above God.”

Faison said that prophetic language is meant to challenge the assumptions and idolatries of a culture.

“We deify capitalism, we deify the military, and none of them are even open for critique. Any time you stand in opposition to that juxtaposition, you’re deemed un-American,” Faison said. “The military fits nicely in that structure. You can’t serve God and the military, that doesn’t mean you can’t serve in the military; it means that you can’t put the military above God.

Blackness, whiteness

The attempt to tie Warnock to figures like Wright or Cone, also misconstrues what liberation theologians mean when discussing concepts of “whiteness” and “blackness.”

“[The Democratic Party] said nothing about Warnock’s demand that Americans repent for their quote, ‘whiteness,’” Carlson said on his show (Warnock actually said that “America needs to repent of its worship of whiteness”). “Now there’s nothing more racist than saying something like that try switching the races around if you don’t believe it … He’s saying that people’s skin color makes them inferior.”

But in the context of liberation theology, “whiteness” and “blackness” represent ways of being (rather than whiteness and Blackness as race or ethnicity), according to Jennings and Rev. Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas, a theologian and dean of Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary who also studied under Cone.

“It is not saying God is anti-white, it’s saying that God stands over against that which signifies or stands for oppression,” Douglas said. “Some of the misunderstandings, willful or not, are simply a refusal to understand the depth of a Black faith tradition that believes in a God who is love, a God who is justice, a God who is freedom.”

Cone’s work spanned from his 1969 Black Theology and Black Power to his 2011 The Cross and the Lynching Tree, which explains Christ as in solidarity with all who are oppressed, likening Jesus’ persecution and crucifixion to the oppression and lynching of Black people in the United States. Cone writes in Black Theology and Black Power that “in America, God’s revelation on earth has always been black, red, or some other shocking shade, but never white. Whiteness as revealed in the history of America is the expression of what is wrong with man [...] God cannot be white.”

“This is a tradition that began and is signified in the spirituals, a tradition that believes in the God of the Exodus who entered into our history on the side of those who are oppressed as they struggle for freedom,” Douglas said. “[W]hen it says that God is Black, it’s saying that God is on the side of those – within our own historical context – that are oppressed and struggling for freedom.”

The campaign against Warnock is using the same tactic that has regularly been employed against Black people seeking to call America to its better possibilities, according to Jennings.

“To try to tie him to Jeremiah Wright and James Cone is to try to return us to the criticisms that were laid at Barack Obama … that he was associated with this radical, anti-American minister,” Jennings said. “Clearly, Cone and all liberation theologians don’t hate white people; what they’re attacking and challenging is a way of being in the world that is destructive to all of life and especially to people of color.”

Jennings said that the best example of drawing this distinction is the everyday lives of Black people. While blackness was originally defined as enslavable and derided, Black people have honored and loved themselves and known that God loved and honored them, Jennings said. Few people racialized as white want to separate how whiteness functioned legally or theologically from their skin color, he said.

“This is the heresy of American Christianity: It imagines America as a reality of good without question,” Jennings said. “People don’t understand that the long tradition of critique and criticism not only has been a part of American democracy, but actually is what has made it come alive in the ways that it has come alive.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!