Being both queer and Christian often means having a front row seat to all the ways the church has failed to embody God’s radical, boundary-breaking love. Even as more churches are welcoming LGBTQ+ folks fully into their pews and pulpits, other Christians are at the forefront of movements to eliminate trans health care, marginalize queer youth, and denigrate those who support LGBTQ+ people.

Yet being both queer and Christian is also about joy — celebrating God’s goodness and the goodness of all who are made in God’s image: trans, asexual, queer, nonbinary, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and all the other labels used to name God’s expansive creativity. In this series, we asked LGBTQ+ Christians to write about the joy of being both queer and Christian. We hope by creating some space for positive expressions of queer Christian faith, we can offer a very clear portrait of the community we want to build: a world and church where LGBTQ+ folks are beloved and empowered.

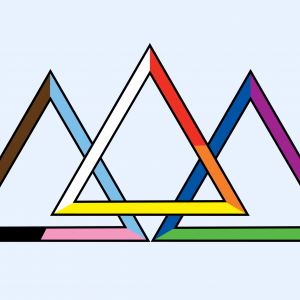

Though some colors have been removed or added over the years for different reasons, six of the original colors continue to exemplify the shared humanity of everyone who marches under their banner. Each color has a meaning that carries deep significance for the LGBTQ+ community. At the same time, there is a biblical connection to the rainbow that speaks to the promises of God. This Pride month, I feel it’s worthwhile to reflect on what each color has to teach us about God and ourselves.

Speech opens a door to previously unknown experiences. In a way, speech — or language — makes and unmakes the world as we know it. When I speak about myself, I tell you the truth of who I am.

So, in an era where people of faith, specifically Christians, are popularizing anti-trans language, it feels like my responsibility to say something — anything — to lift up those of us who identify as transgender and Christian. The truth I want to communicate here is this: God made me to be trans.

“To live fully and authentically.” It’s a phrase that resonates for me as someone who came into their queerness later in life. For a long time, the possibility of living fully and authentically felt just beyond my reach; I felt I was skimming the surface of my being and longed to be fully immersed — soaked and drenched — in who I am. But I was afraid. What would living authentically mean for my place in the world? As a second-generation Korean American who has long struggled to be seen and accepted, I wondered if being queer would foreclose this possibility.

Although the Roman Catholic Church might disagree with me, my Catholic faith revolves not around a man but rather a woman. Her hair is covered in an opaque veil; she wears a long white gown under a blue mantle. Her hands are outstretched and rays of light radiate from her fingertips, pouring down at her sides. Her name is Mary, mother of God, and within her rests the fulcrum of my queer Catholic joy and trauma.

Last weekend, for the very first time in my life, I dyed my hair. I walked into a woman-owned barbershop and gave them permission to change my short hair from its usual very dark brown to an extravagant, and for me, shocking, blonde. Someone else’s hands ran over my tender scalp, creating something new.

My trans nonbinary identity means freedom to step outside of the gender binary. My gender does not define me first; rather, I am first a human and a beloved child of God. This trans nonbinary identity and my Christian faith have always been intrinsically linked; my experience of queer joy is not separate from the joy I have in my salvation. I think of this joy through a trinitarian lens: At its core, my queer joy is the joy of knowing the Father has created my unique identity and calls it very good, that Christ “queers” or subverts the norms of this world, and that the Holy Spirit is continually forming me to love this world as my full self.

Asexuality and aromanticism describe those whose orientations are often defined by lack and rarity. We’re atypical in that we don’t experience sexual and/or romantic attraction, or when we do, it’s the exception to the rule or under certain conditions. We’re inconvenient to remember — on all sides of the political and religious spectrums.