To all the saints, imprisoned and free, in the United States, the world leader in incarceration rates:

“Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ.”

It is likely that the apostle Paul wrote this greeting (Phillippians 1:2) in a prison cell — a reminder that letters to and from prisoners are foundational to the establishment of Christian communities.

Today, for “free” Christians interested in following the gospel commandment to “visit prisoners” (Matthew 25:39-40), corresponding by mail is often a starting point; as a Christian abolitionist, I understand mail correspondence to be one element of revolutionary solidarity with those who are incarcerated. Given the difficulties visitors and chaplains have entering prisons — especially with restrictions on visitations due to COVID-19 — mail is a lifeline for incarcerated people.

But despite the importance of these letters, the Federal Bureau of Prisons is piloting a program to replace physical mail to prisoners with scanned copies, a program I believe is extremely unjust and has urgent implications for the practice of our faith, both for Christians who are incarcerated and Christians on the outside.

As the Prison Policy Initiative reported, the BOP has contracted with the service MailGuard, which will provide incarcerated people with a scanned copy of their correspondence, instead of physical mail. Prison Policy Initiative and Just Detention International have written a detailed report that gives multiple reasons for why this program will be harmful, including adverse effects on incarcerated people’s mental wellbeing and its potential to undermine confidential communications between incarcerated survivors of abuse and their advocates.

Christians should be especially concerned that program will create a barrier for the most vulnerable incarcerated people, such as individuals with disabilities and those in solitary confinement. Furthermore, The Orlando Sentinel reported that Florida’s Department of Corrections is planning to charge prisoners for access to their mail, raising the possibility that other prisons may do the same. Obviously, adding a fee for incarcerated individuals to receive these scanned copies places a grievous burden on the poorest prisoners.

Programs like MailGuard, which make it harder for incarcerated individuals to stay in touch with loved ones, increase isolation and suffering. These programs also deny incarcerated individuals of an essential element of rehabilitation: relationships with family and loved ones in the community — the kinds of communal relationships that make us want to do better and be better. When policies impede this crucial communication, they make rehabilitation that much more difficult.

The physicality of mail matters, too. For those subjected to the hell of incarceration, receiving a piece of mail can feel sacramental, a tactile reminder of the presence of loved ones and hope beyond the present reality, glimpses of divine grace and presence mediated by the physical object.

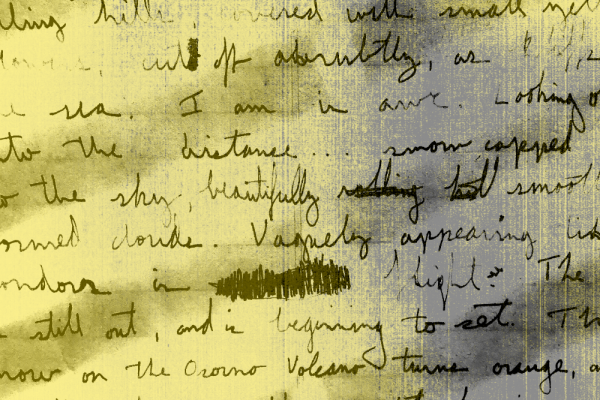

When I started writing to incarcerated people, I was encouraged to send greeting cards with beautiful images that they could hang up on cell walls. I nearly always send cards now — everything from free greeting cards sent by charitable organizations, to cards that I’ve purchased for holiday occasions. I’ve learned that dollar stores are the best place to buy cards for incarcerated people, as their cards typically avoid wishes for special foods or time with families, and instead lean on the religious imagery of thanksgiving, blessing, and resurrection. Another abolitionist suggested sending postcards of places I’d visited or anything interesting from the outside world. So, I began sending postcards as well as liturgies for morning and nighttime prayers, and the people I correspond with have told me they’ve hung those pages by their bunks to pray every day.

And I’ve received material items in return that I cherish: a beautiful Mother’s Day card sent by someone I met in jail, a hand-drawn Christmas card, multiple pages of poems written by one of my long-time pen pals. These letters live directly below the shelf of icons in my dining room; both the icons and the letters act as sacramental objects that point to the divine.

Throughout the letter to the Philippians, Paul writes again and again, “I rejoice,” despite writing from a prison cell. Paul also commands the Philippians to “rejoice” in all circumstances, despite the persecution they were facing. Correspondence with incarcerated people is a joyful, sacramental act of communion as it reminds us that we can draw near to one another when state forces of violence, made concrete in the literal walls of the prison, separate us. Our faith, grounded in Christ’s incarnation, looks to concrete objects as symbols of the divine. The letters written to prisoners become sacramental objects and — much like in the sacraments of communion, baptism, or anointing — this sacramental character has a physical component. Policies that deny prisoners access to their physical mail ignore this sacred reality.

As people of faith, we can oppose this policy by signing on to Just Detention International’s campaign asking U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland to end MailGuard and other restrictive prison mail practices. We can also respond by recommitting ourselves to corresponding with people who are incarcerated. Corresponding with those in prison is sacramental. When we write to those in prison, we are writing to Jesus. In doing so, we impart and experience the joy that comes with sacramental realities, those concrete actions by which God becomes visible among us.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!