Sep 18, 2017

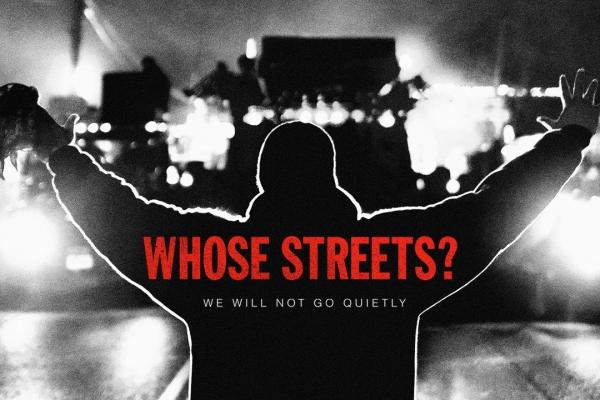

As filmmaking, Whose Streets is dramatic and powerful. As a historical document, it holds even more weight.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login

As filmmaking, Whose Streets is dramatic and powerful. As a historical document, it holds even more weight.