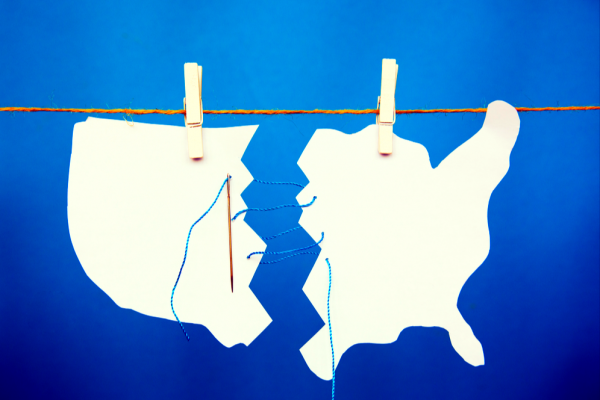

It has been over a month since a mob of violent protesters stormed the U.S. Capitol under the false belief that Donald Trump won the 2020 election. Since then, Joe Biden has been inaugurated as the country’s 46th president. The country is, ostensibly, moving forward.

And yet, the fractures exposed by the election and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic have not been fixed. Only 31 percent of all voters said they think President Biden will be able to unite the country and 56 percent expect partisan divisions to remain the same, according to a recent Quinnipiac poll. Trust in American democracy, and in voting in particular, has eroded.

About 65 percent of registered voters believe the 2020 presidential election was free and fair, according to a recent poll by Morning Consult. Depending on your perspective, that’s either a high or a low number. It’s much higher than October, when only 50 percent of voters believed the election would be free and fair. But compared to other wealthy democracies like Sweden and New Zealand, it’s incredibly low.

“Our systems are very broken,” said Sr. Quincy Howard, OP, campaign director for the Faithful Democracy coalition. “... so deeply broken that I don’t know the full solution.”

The problem, according to Howard, is that there are just so many problems. She says many Americans are justifiably wary of the outsized influence of corporate money in politics, gerrymandering, and historic disenfranchisement. On top of that, there are few federal rules governing the way elections are actually run, making it easier for voters to misunderstand or be misled about the process of voting.

“There were 50 states, all working with different rules,” Howard said of the 2020 election. “In the pandemic, it led to so much confusion.”

So what will it take to restore trust in American democratic institutions, particularly voting? There’s no easy answer. But some experts point to stronger voter protection laws, public education, political accountability for disinformation, and a little bit of faith.

Democracy must include everyone

“The challenge is that people are skeptical, or interested in holding our institutions of power accountable for different reasons,” said Myrna Pérez, who leads the voting rights and elections team at Brennan Center for Justice. There is no single reason that Americans distrust elections. In fact, some of their reasons are in direct conflict with each other.

Many communities of color, and Black communities in particular, have been excluded from democratic institutions, including voting, since the country’s founding. Even after African Americans won the right to vote, many were excluded by poll taxes, literacy tests, voter purges, and long lines at the polls.

“When Black communities see they need to wait four hours to vote and their friends in white jurisdictions can get in and out in 15 minutes, that doesn’t look like democracy,” said Danielle Lang, co-director of voting rights and redistricting at Campaign Legal Center.

“One thing we can do is to say in a loud voice all the time that our democracy works best when it includes all of us,” Pérez said. “We want our institutions of power to be rid of racial discrimination. We want strong laws and practices that demand it and bring it about.”

On the legislative front, there are two pending bills experts believe could vastly improve voter access and voting rights in the United States: the John Lewis Voting Rights Act and the For the People Act.

The John Lewis Voting Rights Act would restore (and bolster) many of the provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that were gutted in the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision, Shelby County v. Holder. The law would require jurisdictions with a history of voter suppression to clear new voting provisions with the Justice Department before putting them into place.

The For the People Act is a sweeping bill that aims to modernize American elections and set a baseline of federal election regulations across the country. Among other things, the law would require same-day registration, early voting, and vote by mail; place restrictions on voter purges; set new campaign finance and ethics rules; and impose stricter criteria on redistricting.

“States would still have power to regulate their own elections, but with a higher floor on how those elections are set up,” Lang explained.

David Carroll, director of the Democracy Program at The Carter Center, says international experience has shown the importance of transparency in elections work. “The institutions, the process. People need to see that sources of official information are very clear and transparent,” he said.

In other countries, this works best when there is a single national election administration, according to Carroll. In the United States, elections are currently managed through a patchwork of state and local rules, making nationwide clarity hard to come by. The For the People Act would go far to address the problem.

It will be no small feat to make sure that all citizens in the United States have equal access to voting. But it may be even harder to disabuse a large segment of the population of the false notion that there is rampant voter fraud.

Confronting the ‘Big Lie’

According to the National Task Force on Election Crises, Trump’s refusal to accept the election results “badly damaged the perception of election legitimacy” and helped lead to the Capitol attack on Jan. 6. That refusal, along with the many “baseless lawsuits” he filed to challenge the results, “likely caused lasting damage to the perceived legitimacy and long-term stability of American institutions and our system of government,” the task force said in a recent report on the 2020 election.

Following the Jan. 6 attack, only about a third of Republican voters said they trusted U.S. elections, according to Morning Consult surveys taken in January. In a Quinnipiac poll taken around the same time, 73 percent of Republicans said they believe there was widespread voter fraud in 2020. Government agencies tasked with monitoring election security have said that there was no indication of massive voter fraud in November.

This false belief in widespread voter fraud is often referred to as the “Big Lie,” according to Lang. This is not a new belief, and has been used for decades as an excuse to make voting more difficult. “It’s part and parcel of the access issue,” she explained.

Lang said there is no easy solution to this disinformation, but that accountability will have to come from politicians, the media, and the courts.

“If we grant this myth legitimacy, it will only grow,” Lang said. “When you have a problem that’s not based on any kind of lack of empirical evidence or facts, but rather about folks with power intentionally evading those facts and sowing distrust, the only way to address that is head on, with accountability.”

There are no quick ways to root out mistrust and misinformation. Most experts who spoke to Sojourners agreed on some changes that might help in the long term, including robust public media and a recommitment to civics education. Many Americans currently don’t understand the nitty-gritty details of how elections are run, making them more likely to believe untrue ideas.

Restoring faith

The report by the National Task Force on Election Crises detailed many recommendations that might improve public trust, including publicly investing in voter education, removing partisan elected officials from running elections, and funding critical election infrastructure.

“I do think faith groups, especially where they already have programs and records of coming together, helping people find common places and common ground, have a really important potential role going forward,” Carroll said.

Faith leaders are also poised to tackle the thorny question of voter trust itself. Trust is an elusive belief. It can be easy to lose and difficult to regain. It can be rooted in feeling just as much as fact. It requires faith.

In October, Washington Post Magazine editor Richard Just wrote about religion’s potential to help repair democracy. Though some of the loudest religious voices in America make religion sound dogmatic, faith is typically a complex endeavor, he wrote.

“Because religion is fundamentally a mystery, it can also be a profound source of analytical humility and existential uncertainty,” Jost posited. “It can teach us to value, even celebrate, contradictions, to think constantly about how we might be wrong — an ethic that is the very opposite of the perpetual certainty now running rampant in American politics.”

Who better, then, to grapple with the big questions that democracy engenders than the faith leaders who have been doing it all along?

“One thing I think faith leaders can do is engage in media literacy and talk to their constituency,” said Francesca Tripodi, assistant professor at UNC School of Information and Library Science. “They can do a lot of good when it comes to contextualizing texts and helping people foster a sense of trust and unity.”

Though they shouldn’t sugarcoat things, faith leaders can also remind their communities that democracy can and does work.

“There’s a lot of noise around this idea that the democratic process isn’t working, but we need to simultaneously recognize that there has been a lot of groundwork,” Tripoldi said. “Part of regaining trust in the democratic process would be to point to more examples where the vote matters.” She cited the recent elections of Sens. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff, both Democrats from Georgia, as examples of strong grassroots and democratic engagement.

Sr. Howard still believes the United States needs “serious reforms” before trust can ever be restored.

“I do think religious leaders have a role in restoring faith [in democracy],” Howard said. “But I think first they have a role in making sure that our systems are actually working the way that they’re supposed to.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!