Muslims

THE U.S. AND other nations are increasingly aware that the so-called Islamic State is a serious, long-term threat to Middle East stability. And it has become clear that there are few good options for addressing the situation without the willingness and ability of the Iraqi government to promote inclusion and weed out corruption.

In the midst of all this, the plight of Iraqi Christians has taken center stage. Since the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, more than two-thirds of the Iraqi Christian community has left the country, with many fleeing as a result of violence and religious persecution.

This exodus has only increased as the reach of the Islamic State, or ISIS, has expanded and its reputation for brutality become widely known. The militant group has publicly beheaded hostages for propaganda purposes, committed mass killings, and given Christians the ultimatum: Convert to Islam, pay a fine, or face death if they remain faithful to their beliefs.

Followers of Christ have existed in the area now called Iraq since the earliest days of Christianity. Now there is a serious debate as to whether the faith has a viable future in this ancient of lands.

ISIS terrorist rampages, waves of anti-Muslim hate speech and fear-mongering Islamophobia are inspiring an outburst of online activism in the form of Twitter hashtags.

The question is: Does it work, especially over the long term?

An army of “clicktivists” — a mix of earnest advocates and pointed satirists — has entered the fray armed with 140-character positive, peaceful or humorous counter-messages.

Using names such as #TakeOnHate, #IStandUpBecause, and #NotInMyName, the pushback approach promotes the complexity, diversity and positive contributions of Islam and Muslims. Others, such as #MuslimApologies, offer sarcasm in service of the same message.

Yet the hashtags are often immediately co-opted by trolls spewing an opposite message. And some experts question whether clicktivist campaigns have lasting worth.

Linda Sarsour has no doubt they do. She’s a Brooklyn-based Palestinian activist in the streets and on social media and a co-creator of #TakeOnHate. The hashtag is accompanied by a resource website, launched in March by the National Network for Arab American Communities.

“The insidious thing about anti-Arab hate speech is that it seems to be acceptable, where the ‘N-word’ or anti-Semitic remarks are not taken with the same degree of outrage,” said Sarsour, who was chased down the street in September by a man who was later arrested for threatening to behead her.

A campus appearance by Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the outspoken Muslim-turned-atheist activist, is being challenged again, this time at Yale University where she is scheduled to speak Sept. 15.

While her previous campus critics have included members of religious groups, especially Muslims, this time the critics include Ali’s fellow ex-Muslims and atheists.

“We do not believe Ayaan Hirsi Ali represents the totality of the ex-Muslim experience,” members of Yale Atheists, Humanists and Agnostics posted on Facebook Sept. 12. “Although we acknowledge the value of her story, we do not endorse her blanket statements on all Muslims and Islam.”

Those statements include calling Islam “the new fascism” and “a destructive, nihilistic cult of death.” She has called for the closing of Muslim schools in the West, where she settled after immigrating from her native Somalia, and is a vocal advocate for the rights of women and girls in Islam.

When I first saw Americans joining in solidarity with Iraqi Christians through the #WeAreN hashtag and protest campaign, I was encouraged. Our team at Preemptive Love Coalition had been sounding the alarm about the targeted persecution of minorities in Iraq through private emails and social media messages for weeks, in between making urgent appeals in our effort to provide lifesaving heart surgeries for children amid the violence.

Most of our efforts were largely unsuccessful before the “Islamic State” gave Mosul’s Christians an ultimatum to (1) convert to Islam; (2) pay a submission tax; or (3) “face the sword.”

After Islamist militants began marking the homes of Christians in red paint with the Arabic letter “N” (Nazarene) for extermination or expropriation, we tried again to use our proximity to the problem in Iraq to provoke our friends in America to pay attention by tagging a photo “#WeAreN,” in which I had symbolically marked myself with an Arabic “N.”

But it was not strictly an act of solidarity with Iraqi Christians. We had the targeting of Turkmen, Yezidi, Shabak, and even Sunni Muslims in view, as well. #WeAreN was more about the marking of Christians; less about the marking of Christians.

Muslims and minorities across Iraq immediately sensed the gravity of the tactics deployed by the Islamic State: if one group is marked, we are all marked. If we stand by in silence today while others are marked for extinction, our time will come, and there will be no one left to stand for us.

In response, Muslims across Iraq joined together in protest, prayer, and viral photographs saying “We are Iraqi. We are Christians.”

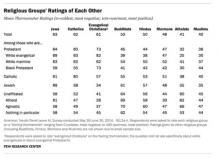

A new Pew Research survey finds U.S. adults feel most warmly about people who share their religion or those they know as family, friends or co-workers.

Americans give their highest scores to Jews, Catholics, and Evangelicals on a zero-to-100 “thermometer” featured in the survey, “How Americans Feel about Religious Groups,” released Wednesday. They’re nestled within a few degrees of each other: Jews, 63; Catholics, 62; evangelicals, 61.

In the middle of the chart: Buddhists, 53; Hindus, 50; Mormons, 48. Trending to the chilly negative zone: atheists at 41 and Muslims at 40.

Pew took the thermal reading because “understanding the question of how religious groups view each other is valuable in a country where religion plays an important role in public life,” said Greg Smith, Pew’s associate director of religion research.

THE VIOLENCE AND kidnappings in Nigeria are more than a religious conflict: They are a political manipulation of religion.

Before the 2011 Nigerian election, northern politicians (who are mostly Muslims) threatened to make the country ungovernable if Goodluck Jonathan, a Christian from the south, became president. Jonathan was vice-president for Umaru Musa Yar’Adua, a Muslim from the north, who died before completing his eight-year term. Jonathan assumed power after Yar’Adua’s death, as is allowed by the constitution. However, northern Muslims claimed that since Yar’Adua did not finish his term, they should be allowed to place someone of their own choosing in power. Jonathan’s refusal angered the north.

In response, the Muslim terrorist organization Boko Haram began intensifying its attack on Jonathan’s rule in order to discredit his presidency and his pursuit of the 2015 election. If Boko Haram succeeds in pushing Jonathan out, southern militia groups are likely to commence their own violent campaign. These terrorists are trying to manipulate people by making them think that it is a religious fight, when in reality it is about political power.

People, however, are beginning to reject the violence. In April, as the world is well aware, Boko Haram kidnapped more than 200 schoolgirls from Chibok, a community that is said to be about 90 percent Christian. The outcry of rage and pain about this incident transcended religious lines. In a May market bombing in the city of Jos, both Christians and Muslims lost their lives. After the bombings, Muslims and Christians on the streets of Jos tried to work together in finding a way through the situation. People no longer want to fight and are starting to value peacebuilding and interfaith efforts. This is a sign of hope.

As the number of Muslims in Bangui, the Central African Republic capital, dwindles to an estimated 900, the head of a global alliance of churches has urged tackling the conflict from a political rather than a religious angle if the Muslim exodus is to be reversed.

The alliance is one of the agencies providing humanitarian assistance in the country, where chaos erupted last year after the mainly Muslim rebels toppled the government.

The Seleka rebels looted, raped, and killed mainly Christian civilians, prompting the formation of an equally brutal pro-Christian anti-Balaka (anti-machete) militia.

Secretary of State John Kerry brought his argument for a two-state Israeli-Palestinian peace to the annual AIPAC conference this week, and whatever else we might know, we know this: Many evangelical Christians didn’t like it.

Or at least that’s what we’re told by some Christian leaders and their political allies. Supporting Israel’s government by opposing compromise with the Palestinians is a permanent plank in American evangelical political thought. “God told Abraham that he would bless those who bless him and the nation of Israel,” the thinking goes, “and curse those that curse Israel.”

But could it be that the truth is more complicated?

What if the loudest evangelical voices don’t represent the complexity of our community? I raise these questions as an evangelical who is fully committed to supporting the struggle for security, dignity, and freedom for Israelis and Palestinians. And I’m not alone.

Foreign law bans are back.

For the fourth year running, Florida is trying to outlaw the use of foreign and international law in state courts. Missouri has mounted another attempt to pass an anti-foreign law measure after last year’s effort was vetoed by Gov. Jay Nixon. The bans also have crept farther north, making a debut in Vermont.

These laws, which have passed in seven states, are the brainchild of anti-Muslim activists bent on spreading the illusory fear that Islamic laws and customs (also known as Shariah) are taking over American courts. This fringe movement shifted its focus to all foreign laws after a federal court struck down an Oklahoma ban explicitly targeting Shariah as discriminatory toward Muslims.

A generation or two ago, when America’s Muslims were new immigrants who made up an even smaller minority of Americans than they do today, they viewed the lights, trees, carols, gifts, and festive spirit of Christmas as a threat to their children’s Islamic faith.

But these days, a growing number of Muslims celebrate Christmas, or at least partake in some ways, even if they don’t decorate their homes with trees and a light show. Indeed, many Muslim families have created their own Christmas traditions.

“I teach my three children, who attend public school and happen to be born into an interfaith Christian-Muslim family, that we absolutely do celebrate Christmas because we are Muslim,” Hannah Hawk of Houston wrote in an email. Rather than putting up a tree or lights, “we celebrate the reason for the season, Jesus, by studying all that is written about him in the Quran and by examining historical theories.”

NEW DELHI — Police in India’s capital used water cannons and canes on peaceful Christian and Muslim leaders Wednesday while they were demanding equal constitutional protections.

Organized jointly by confederations of churches and Muslim groups in India, the demonstrators demanded affirmative action for Dalits (formerly “untouchables”) who have converted to Christianity or Islam.

Only Dalits who have converted to Hinduism, Sikhism, or Buddhism are entitled to affirmative action slots in jobs and educational institutions, among other protections.

At the end of a three-day tour, the Saudi-based Organization of Islamic Cooperation told Buddhist-majority Myanmar to repeal “laws restricting fundamental freedoms” after more than 240 Muslims were killed by Buddhist mobs during the past year.

Before the OIC delegates left Myanmar on Saturday, they visited minority ethnic Rohingya Muslims who fled the violence and are now living in squalid camps along the border with Bangladesh in Myanmar’s Arakan state, also known as Rakhine.

Headed by Secretary General Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, the OIC delegation called on the government to continue legal reforms, The New Light of Myanmar newspaper reported.

It may be as close as a person can get to praying at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Western Wall, without actually going there.

The newly released movie “Jerusalem,” filmed in 2D and 3D and playing on IMAX and other giant-screen theaters across the U.S. and the world, gives viewers grand, hallmark panoramas, at once awe-inspiring and intimate.

For years filmmakers had sought the rights to capture the city from the air, but never before had permission been granted, in part because the holy city is a no-fly zone.

Still, before filming began in 2010, producer Taran Davies came up with an extensive wish list of all the sites and rituals he wanted in the film, and presented it to advisers familiar with the spectrum of religious and secular officials who would have to approve.

“They all laughed and said forget about it,” Davies said. “They said, ‘It’s impossible and you’re not going to get half of what you’re looking for.’”

MY HEART WAS broken when I got the news on a Sunday in September: All Saints Church in Peshawar, Pakistan, had been attacked by two suicide bombers just after the Sunday service, as worshippers filtered out of the sanctuary. Eighty-five people were killed, including 34 women, seven children, and two Muslim police officers there to provide security. Later reports said the bombers were Sunni extremists.

In 1976, I was honored to start Youth for Christ in Peshawar. There were few Christians in this area near the Afghan border; Peshawar was not and is not a big town. Undoubtedly, some of the adults in and around the church when it was bombed were people I had met decades earlier.

News of the bombing confounded my memory of Peshawar 38 years ago. Religious plurality then was not perfect, but it was in great contrast to today. Christians, though few, served the Lord with some freedom. Youth for Christ held open-air rallies in the park, amplified by public-address speakers, with young people singing Christian songs with Bible messages to be heard by anyone within earshot. No security was needed, and truth be told both Muslim and Christian youth were in the audience and the choir.

The start of the second Gulf war in 2003, and subsequent military actions, changed everything. Reports say the church bombing in Peshawar was in retaliation for U.S. drone strikes that killed innocent men, women, and children, along with suspected terrorists, in that part of Pakistan. Peshawar is strategically located on the border with Afghanistan, not far from the famous Khyber Pass and only about 125 miles from where Osama bin Laden was killed.

After decades of polarization along religious lines, Christians and Muslims in Egypt are coming together to rally behind their flag.

The country is in the midst of a swell of nationalism that began during the revolution in 2011 and intensified when citizens took to the streets in June of this year to call for the removal of President Mohammed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Egyptian flags adorn houses and buildings throughout the capital, and everything — from sandbags buttressing military blockades to pillars along the Nile Corniche — has been painted in the national colors of black, white, and red.

Shortly after teenagers beat up a Columbia University physician Saturday, a Muslim woman was attacked a few blocks away.

It is not clear whether the attacks on Dr. Prabhjot Singh and the Muslim woman, who were both treated at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, are related. But many say the motives, if not the perpetrators, are depressingly familiar.

They are part of a long line of assaults on Sikhs, who are sometimes mistaken for Muslims; on Muslims; and, more generally, on people perceived as foreigners.

“The mosques are our barracks, the domes our helmets, the minarets our bayonets and the faithful our soldiers.”

This was the Islamist poem quoted by the mayor of Istanbul, Turkey, in December 1997. Charged with using inflammatory speech, he was ejected from office and sentenced to jail by the Ankara High Court.

Today, that mayor, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is prime minister of Turkey. During a decade in office, he has slowly but inexorably pushed secular Turkey, a member of NATO, toward an unabashedly Islamist future.

As a Muslim, I refuse to give up Islam to the Islamists. So should others who believe in a deeply pluralistic Islam of the sort my Indian-born grandparents taught. It is the only path to peaceful resolution of inevitable religious differences, within Islam and with other faiths.

Yet today pluralist manifestations of Islam are contracting. Never before has there been a time when Islam has been more threatened from within. That threat today is twofold: ideological and sectarian.

In their holiday Eid al-Fitr khutbas, or sermons, on Thursday many imams across the country noted a growing climate of acceptance in America but urged Muslims not to forget the problems facing their communities in the U.S. and overseas.

“The Eid khutba is like the State of the Union address,” said Oklahoma-born convert Suhaib Webb, imam of the Islamic Society of Boston Cultural Center, the biggest mosque in New England, to an overflowing crowd — men dressed in crisp robes, tunics, and three-piece suits, women in black abayas, long floral wraps, and colorful headscarves.

“Our community is at a unique crossroads,” Webb said, issuing a call for older Muslim generations to allow younger generations to have greater roles in community affairs. “There are a lot of young people with a lot of excitement, and a lot of old people with a lot of fear. And that’s not a healthy thing.”

Bio: "Khaipi" (real name withheld) is a peace studies professor in Thailand and a Chin religious freedom activist who served as researcher for the Chin Human Rights Organization's 2012 report detailing abuses against ethnic and religious minorities in Burma.chro.ca

1. What is at the root of the persecution of Christians in Burma?

There is an unwritten policy called “Burmanization,” which means that to be Burmese you have to be a Buddhist and you have to speak Burmese. The Chin people are not allowed to practice Christianity, and we are not allowed to study our own ethnic languages. But it’s not all about religion: They are attacking our ethnic identity because Christianity has become our identity.

Before Christianity came to the Chin people, they practiced an indigenous religion. In this religion, they believed in an Almighty One who created the world. In 1899, the very first American Baptist missionaries came to Chin state, and when they talked about the Christian God, our forefathers could adopt it very easily because it was very close to that indigenous belief. Today, when the Burmese military junta persecutes us, they say, “Okay, we want to take out this kind of Western religion.” But for us, once we believed in God, it became our religion, not a Western religion anymore.

![U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry shakes hands with Raymond Kelly. Photo courtesy U.S. Department of State, via Wikimedia Photo courtesy U.S. Department of State [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://sojo.net/files/styles/medium/public/blog/512px-U.S._Secretary_of_State_John_Kerry_shakes_hands_with_Raymond_Kelly_Commissioner_of_the_New_York_City_Police_Department_NYPD-427x284.jpg)

Muslim-American groups are mounting a growing campaign to quash the potential nomination of New York City Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly as the next secretary of the Department of Homeland Security.

Muslims say that as head of the nation’s biggest police force, the commissioner oversaw a spying program that targeted Muslims based solely on their religion, showed poor judgment by participating in a virulently anti-Islamic film, and approved a report on terrorism that equated innocuous behavior such as quitting smoking with signs of radicalization.

Homeland Security chief Janet Napolitano announced she is resigning in September to become president of the University of California system.

“Mr. Kelly might be very happy where he is, but if he’s not, I’d want to know about it, because obviously he’d be very well qualified for the job,” President Barack Obama said in a July 16 interview with Univision.

Muslims are particularly indignant because Obama said on numerous occasions that he would work to end profiling.