Mental Illness

SOME TV SHOWS are as great as our greatest literature. Programs such as The Sopranos, The Wire, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad are Dickensian in their sprawl and Shakespearean in their tragic characters’ deceptions. But one show in this current Golden Age of television is the most oft-overlooked of its peers, one whose greater feat—or unfairness to screenwriters—is that it’s not scripted. I’m talking about A&E’s reality show Hoarders.

I’m not kidding. What often draws people to watch those suffering from hoarding disorder and the psychologists, professional organizers, and loved ones trying to help them overcome mental illness is the typical reality TV magnet: Seeing the life of someone worse off than you. But there’s more to Hoarders than that. A good episode is nothing less than a short story similar to those by Alice Munro, vivid in its deep analysis of real life, family dynamics, and psyches in danger and repair. Almost every night for the past month, watching has been like studying fiction writing in some of the best (and cheapest) creative writing courses I’ve ever taken.

EVEN IN MY earliest memories, I was consumed by terrifying worries and did everything in my power to alleviate my deepest fears. When I was 8, I can remember being plagued by guilt following the death of my aunt to cancer, worrying that it was somehow my fault. Intrusive thoughts and images flooded my mind at night, and I called my parents into my room to confess, seeking reassurance that I was not a dangerous monster. As I grew older, my fears began to consume every single area of my life that was important to me. By college, I was afraid to sleep out of fear that I had left the stove on or the door unlocked. And by graduate school, I moved through my day wondering if I had called people derogatory names or written horrific things in birthday cards before blocking the memories out. I repeatedly checked the stove, took pictures of locks, and called friends to make sure I hadn’t somehow caused harm. At the time, I was unaware that these acts, known as “compulsions,” only made my condition worse.

In my early 20s, I learned that I was experiencing the symptoms of a diagnosable mental illness known as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). OCD is often represented in television and movies as something laughable—think Tony Shalhoub’s Monk. In reality, OCD is far more serious: a debilitating disorder defined by unwanted obsessions that terrify the sufferer and compulsions repeated over and over to alleviate overwhelming fear, guilt, or anxiety. Some obsessions might relate to more commonly known themes of contamination or organization, while others might include culturally taboo themes involving violence or sex. But they are all equally painful to those caught in OCD’s grasp.

We all have thoughts—happy, sad, violent, intrusive, and strange. But those with OCD tend to place more value on these thoughts, concerned that they may be true. When time spent experiencing these obsessions and engaging in compulsions impedes functionality, that’s when it becomes a disorder. But even in my struggles, I feared documentation of an official diagnosis would negatively impact my pursuit of ordination. I had always heard that we should turn our worries to God, so I wondered what those approving my psychological evaluations for ministry would think if they viewed me as in need of mental health treatment that could not be solved through prayer.

HOW DO WE love someone with a mental illness? In a NAMI blog post titled “How To Love Someone With A Mental Illness,” the writer notes, “Choosing to love someone who acts or feels unlovable can be part of what helps them see they are valued as a whole person, they are not the sum total of their pain … Mental illnesses are illnesses, and sometimes they can change someone’s circumstances … they can even change their personalities for a time, change their interests, their spirit. But they are the same person you have always loved, and they need you to see that person in them—even when they can’t see themselves clearly” (emphasis mine).

After all, mental illness does not change the fact we are beloved children of God. Even though they are the same person you have always loved, it can be hard to recognize them. Looking through God’s eyes helps us to see past the label and the diagnosis.

A great example of “choosing to love” came to me through a story from my friend Monique. Over lunch, I asked Monique what I thought was a philosophical question about marriage and mental illness. The conversation turned personal very quickly, however.

Monique shared with me that her vision for her marriage is to flourish, knowing both she and her partner have mental illness. She said flourishing for their marriage happens when they are up front with each other about their mental health status, can state their needs, and can get the support they need.

Reprinted with permission by Chalice Press.

For some, joy comes in the morning after a passing night. Others might require special, prolonged attention and a slew of various helps to cope through a night that lasts years, that seems to hijack all of life — and this is not just true of the chronically ill, but many who might be bound by trauma or unbearable grief.

Liberty and freedom aren’t fancy words or individual guarantees. They’re a process that requires everyone’s participation. We can’t have liberty and justice for all until we’re willing to see the injustice and the lack of liberty all around us, and commit ourselves to doing something about it.

My depression is frustratingly, deeply, a part of me. My brain chemistry is wired in such a way that I struggle, through no fault of my own. But I do not struggle alone. As a Christian leader, this is my fervent hope and prayer.

To adults new to Christian practices of fasting during Lent, the idea can seem facetious — some sort of trendy way of worshipping both Jesus and our own well-defined abs. But for many, fasting has been a way of cleansing not the body but the mind. Temporary self-denial can invite us to compassion for those who are hungry not by choice, to a remembrance of the trials of Jesus, or to better appreciation of food when we do eat. But in the face of a world that already pressures many into self-denial, self-deprivation, and self-harm, the strength of the spiritual discipline of fasting cracks.

Across Africa, many people believe mental illness is caused by curses, witchcraft, or demons. In such places, traditional medicine has long remained the first line of treatment. But a novel program in Eastern Kenya is working to change those perceptions and help the mentally ill receive better care.

We’d really like to have an explanation that makes these killers “other” than the rest of us. So we say they are mentally ill and demand our society do a better job caring for them.

While it’s true that we need to do a better job caring for the mentally ill, the vast majority of people with mental illness will never harm anyone. Mass murderers don’t tend to be mentally ill.

I started this year in solitary confinement.

It’s not that I am regularly in prison or that I had behaved so badly. I was simply in a mock solitary cell located in the sanctuary of a church. I was only there for an hour. I knew I would be getting out.

But that hour did offer a glimpse into the world of how solitary confinement is used – and abused – in our nation’s prisons. And it offered a glimpse at the reform efforts that are gaining steam all across the country, including in my home state of Wisconsin.

When Kate Edwards, a Buddhist chaplain who has worked in the Wisconsin prison for the past five-and-half years, closed the door behind me, I was alone, but hardly in silence.

The Supreme Court — the last stop for condemned prisoners such as Scott Panetti, a Texan who is mentally ill — and whose case was just stayed by an appellate court — appears increasingly wary of the death penalty.

In May, the justices blocked the execution of a Missouri murderer because his medical condition made it likely that he would suffer from a controversial lethal injection.

Later that month, the court ruled 5-4 that Florida must apply a margin of error to IQ tests, thereby making it harder for states to execute those with borderline intellectual disabilities.

In September, a tipping point on lethal injections was nearly reached when four of the nine justices sought to halt a Missouri prisoner’s execution because of the state’s use of a drug that had resulted in botched executions elsewhere.

And in October, the court stopped the execution of yet another Missouri man over concerns that his lawyers were ineffective and had missed a deadline for an appeal. The justices are deciding whether to hear that case in full.

Last week’s school shooting in Marysville, Wash., has us all asking the question again: Why did this happen?

Snohomish County Sheriff Ty Trenary gave voice to the despair many are feeling as we search for answers. “The question everybody wants is ‘Why?’ I don’t know that the ‘why’ is something we can provide.”

Why did Jaylen Fryberg text his friends and family members to join him for lunch only to shoot them and then shoot himself? Whenever these tragedies occur we are tempted to blame the shooter by making him into a monster. We label the shooter “mentally ill,” claim that he was isolated from his peers, or was a generally troubled youth.

The answer to the question “Why?” has usually been to blame the shooter. We make the shooter into a monster because it allows us to make sense of senseless violence. Why did this tragedy happen? Because he was evil.

But Fryberg’s case won’t allow such easy answers. By all accounts, he was a popular and happy young man, seemingly incapable of causing such harm.

This horrific shooting is so scary because no one saw it coming. If a popular kid like could commit such a heinous act, anyone could do the same. Fryberg’s case deprives us of the easy out of blaming another. The only thing left is to face our own violence.

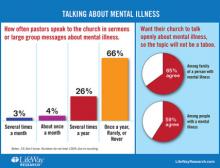

Protestant clergy rarely preach about mental illness to their congregations and only one quarter of congregations have a plan in place to assist members who have a mental health crisis, a new LifeWay Research survey found.

The findings, in a nation where one in four Americans have suffered with mental illness, demonstrate a need for greater communication, said Ed Stetzer, executive director of the evangelical research firm, a ministry of LifeWay Christian Resources, which is an agency of the Southern Baptist Convention.

When it comes to mental illness, researchers found:

- 66 percent mention it rarely, once a year, or never

- 26 percent speak about it several times a year

- 4 percent mention it about once a month

- 3 percent talk about it several times a month.

“When we look at what we know statistically — the prevalence of mental illness and the lack of preaching on the subject — I think that’s a disconnect,” said Stetzer.

It feels awkward and even a bit inappropriate to be talking about ‘celebrity news’ when so much is going on around the world: Iraq, refugees in Syria, children stranded at borders, Michael Brown’s death and Ferguson, Ebola, Ukraine, and the list tragically goes on.

But then again, it feels appropriate because it’s another reminder of the fragility of our humanity.

As has saturated the news, Robin Williams passed away this week. His life ended way too short at the young age of 63 – apparently because of suicide. While this was news to me, Robin had been struggling with intense depression – especially as of late — and was recently diagnosed with Parkinson's Disease.

To be honest, I don’t get caught up too much on celebrity happenings mainly because there’s not much genuine connection. I don’t really know them personally. Make sense? Robin Williams’ death – on the other hand – just felt like a painful punch in the gut. Perhaps, it’s because Mork and Mindy (Nano Nano) was the first TV show I watched (along with Buck Rodgers) after immigrating to the United States. I deeply resonated with Mork – this ‘alien’ or ‘foreigner’ from another land trying to fit in. Perhaps, it’s because so many of the characters he played in countless movies influenced me on some level as it did so many others.

Yesterday morning I was prepared to write about being a sacred place where others could come for healing, encouragement, and restoration. I had no idea Robin Williams committed suicide yesterday. I didn't hear the news because all evening I was sitting with a friend who is going through one of the most difficult times in her life. I also rushed out the door this morning with two friends on my heart who were also going through a great deal of suffering. It was late morning before I found out Robin Williams passed away. Robin Williams, the great comedian? The one who warmed my heart in Patch Adams. The man who challenged me, through Patch Adams, not to just be a professional, but a professional who cared for people.

I've read a lot of posts on Facebook about how we (those still living) never know what a person is going through on the inside. I've read that a person can be smiling on the outside, but hurting on the inside. While this is certainly true for some, I find many who are hurting tell us they are hurting. In their efforts to reach out, we often shut the door on them. Sure, the first time or two we listen and tell them we are going to pray for them, but then they become "needy." I don't know how many times Christians have warned me to stay away from a person because they are "needy" or "too clingy." I remember one time thinking, "Why wouldn't they be needy?" I thought this because we both (the commenter and I) knew the horrible situation our sister was in. I couldn't imagine the pain she was going through. However, this person believed our sister in Christ was being too "needy."

While I believe that we should never replace God by trying to be the Savior, I do believe we should be a place where those who are hurting can come.

That a “universally beloved” entertainer such as Robin Williams could commit suicide “speaks to the power of psychiatric illness,” mental health experts say.

Williams, who died Monday at age 63, had some of the risk factors for suicide: He was known to have bipolar disorder, depression, and drug abuse problems, said Julie Cerel, a psychologist and board chair of the American Association of Suicidology.

People who are severely depressed can’t see past their failures, even if they’ve been as successful as Williams.

“With depression, people just forget,” said Cerel, who is also an associate professor at the University of Kentucky. “They get so consumed by the depression and by the feelings of not being worthy that they forget all the wonderful things in their lives.”

They feel like a burden on their family and that the world would be better off without them.

“Having depression and being in a suicidal state twists reality. It doesn’t matter if someone has a wife or is well-loved,” Cerel said.

Williams was certainly beloved, as shown by the outpouring of grief and sympathy on social media outlets Tuesday night.

I log onto Facebook every day. It tells me that it’s OK to talk about a bad date, to engage in family arguments for all to see, or even to display how envied one believes him/herself to be via self-portraits from a bathroom mirror.

Let’s be honest. Social media has caused an eruption of platforms in which people across the globe feel comfortable laying it all out there. There is a certain acceptance of divulging personal information that my parents’ generation wouldn’t dare ever bring up in a private forum, much less a public one. This phenomenon raises the question: If it’s OK to talk about almost anything these days, why are important topics still being held captive in the land of anonymity?

Abortion. Incest. Rape. Bankruptcy. Depression. Mental illness.

And then there’s suicide.

So why write about it now? Because I fell into the trap of ignoring an important topic simply because it had never hit close to home. And then came the phone call.

Sharing how he has coped after his son’s suicide last year, megachurch pastor Rick Warren, urged Southern Baptist pastors to let their times of suffering be acts of ministry.

Warren’s son, Matthew, 27, who suffered from mental illness, killed himself five days after Easter in 2013.

“If your brain doesn’t work right and you take a pill, why are you supposed to be ashamed of that?” Warren asked. “It’s just an organ, and we have to remove that stigma.”

A few weeks ago, I asked folks on Twitter, and specifically, my colleague Amy Simpson, who has recently published a book on mental illness and the mission of the church:

What do you think about the way people use words like “bipolar,” “crazy,” and “manic” when they really mean “moody,” “energetic,” “quirky” and even “fun?"

It’s part of a pattern I’ve noticed lately — and maybe you’ve noticed it too.

People with beautiful head shots, flawlessly designed websites, and enviable accomplishments insist that they are really just a ‘mess.’ Or that their families are ‘crazy.’ Or that their homes and lives are every bit as complicated and frustrating as everyone else’s … meanwhile, their Instagram feeds show nothing but beauty; if ‘chaos’ is there, it’s only ever of the picturesque kind.

There are no birdcages sprouting stalagmites and stalactites of bird droppings. There are no snotty-nosed, unwashed, half-dressed, hungry children who’ve never visited a dentist in their lives. There is food in the fridge and on the table, and it isn’t even growing mold or crawling with roaches or undulating with maggots. In fact, it’s from Trader Joe’s and may even be organic! There is no broken glass or police officers showing up because the neighbors heard screaming. There is electricity and running water and indoor toilets.

Yeah, there’s raised voices and tempers and conflicts. But that makes you human. Not crazy. Not dysfunctional. Not “a mess.”

Editor's Note: The following is the text of a sermon preached on Oct. 7 at the weekly chapel service at American Baptist Seminary of The West in Berkeley, Calif.

A woman struggling with postpartum depression died last week, killed either when her car crashed into the gates of the White House or by the bullets fired upon her by security guards and police. Her child survived without physical injury.

Social media were alive with speculations of terrorism, domestic or international, with connections between this incident and the government shutdown, with any number of theories about gun violence. We were ready for it. Raw and weary before the story even came to light, we were primed for the explosion of speculation and public bewilderment.

Have you not known?

Have you not heard?

It's a terrible story from every angle. We have so many such stories describing what is happening in our nation lately. We have much of ourselves invested in every aspect of the shutdown.

We are raw.

The spiritual noise is deafening.

We are rendered blind by all we see. It is too much.

It is as if the prophets are silenced;

souls have been rendered mute, blind, and deaf.

Have you not known?

Have you not heard?

Events such as these touch a raw place in our souls. Our souls struggle to proclaim the greatness of the Lord. So we turn instead to the sourness of our neighbor. We proclaim their deficits to the highest heaven.