martin luther

On Monday, Oct. 31, in Sweden, Pope Francis will take part in an ecumenical service commemorating the beginning of the Protestant Reformation’s 500th year.

It is stunning to think the start of this momentous anniversary features a visit from the Roman pope.

And it raises a question: Does the Reformation still matter?

Nearly 500 years after Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the Castle Church door, the largest Lutheran denomination in the U.S. has approved a declaration recognizing “there are no longer church-dividing issues” on many points with the Roman Catholic Church.

Image via Molodec/Shutterstock.com

Oct. 31 is approaching quickly — a day marked throughout the United States by costume contests, pumpkin carvings, and children knocking on neighbors’ doors with questions of “trick or treat?”

But for Protestant churches around the world, Oct. 31 is also a celebration of a grown man knocking on a (rather large) door, asking a different question of the Catholic Church:

From whom does salvation truly come? And a follow-up: How do we refocus the church on the Gospel?

On this date, almost 500 years ago, Martin Luther hammered his 95 Theses onto the front doors of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg, Germany — an act that, unforeseen by Luther at the time, is now credited with beginning the Protestant Reformation. Luther’s 95 Theses outlined his abstentions to the practice of selling indulgences to guarantee Christians salvation, emphasizing that grace is given by God alone and can only be assured by the clergy, not bought from them.

With the help of the social media of his day — the newly-improved printing press — news quickly spread to people throughout Europe that Martin Luther was questioning the papacy and attempting to refocus the church’s theology on forgiveness through the word and the eucharist, neither of which required financial prosperity. Within a few years, Martin Luther was excommunicated from the Catholic Church for his continued teachings, which included suggestions that the Bible should be accessible to all people and that priests not necessarily need to be celibate.

The Reformation gathered Christians from across Europe into a community of “rebels,” from which multiple denominations would spring up over the next half a century.

Today, 498 years later — with of a Catholic pope nicknamed “The Peoples’ Pope,” who is on Twitter and preaches about income inequality — what would Luther think of the state of the church?

Pope Francis leads the “Via Crucis” (Way of the Cross) procession, which commemorates the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, at the Colosseum in Rome on April 3, 2015. Photo via REUTERS / Alessandro Bianchi / RNS

Despite Luther being thrown out of the Catholic Church during his lifetime, the Vatican reacted positively to news of the square’s upcoming inauguration.

“It’s a decision taken by Rome city hall which is favorable to Catholics in that it’s in line with the path of dialogue started with the ecumenical council,” said the Rev. Ciro Benedettini, deputy director of the Vatican press office, referring to a gathering of churchmen to rule on faith matters.

Image via Fabio Freitas e Silva/Shutterstock

Even on a local scale, problems like poverty and hunger can overwhelm our imaginations. My own city of Lancaster, Pa., is like countless others. Pockets of true poverty cluster in the old city and dot the countryside. Affluent developments surround the city, while hip new housing is popping up in the center of the city. An impressive urban revitalization campaign has transformed the city’s image, making downtown an attractive place to eat, shop, and play.

Recently, however, a study by Franklin and Marshall College has shown that Lancaster’s resurgence has not helped its poorest residents. Just the opposite has occurred. Between 2000 and 2013, per capita income has grown by 20 percent in the city’s center while it has declined in every other section. What looks like progress from the outside contradicts the harsh reality that thousands experience.

It’s a typical scenario, in which outcomes such as life expectancy and high school completion rates vary dramatically, even in adjacent zip codes and school districts. Faced with such stubborn realities, many individuals feel at a loss concerning how to make a difference.

This Nov. 2, on what is known as All Souls’ Day, Roman Catholics around the world will be praying for loved ones who have died and for all those who have passed from this life to the next. They will be joined by Jerry Walls.

“I got no problem praying for the dead,” Walls says without hesitation — which is unusual for a United Methodist who attends an Anglican church and teaches Christian philosophy at Houston Baptist University.

Most Protestant traditions forcefully rejected the “Romish doctrine” of purgatory after the Reformation nearly 500 years ago. The Protestant discomfort with purgatory hasn’t eased much since: You still can’t find the word in the Bible, critics say, and the idea that you can pray anyone who has died into paradise smacks of salvation by good works.

The dead are either in heaven or hell, they say. There’s no middle ground, and certainly nothing the living can do to change it.

Many Catholics don’t seem to take purgatory as seriously as they once did, either, viewing it as fodder for jokes or as the “anteroom of heaven,” an unpleasant way station that is only marginally more appealing than hell.

But Walls is a leading exponent of an effort to convince Protestants — and maybe a few Catholics — that purgatory is a teaching they can, and should, embrace. And he’s having a degree of success, even among some evangelicals, that hasn’t been seen in, well, centuries.

I was born in 1990. That puts me squarely in the middle of what is referred to as the millennial generation.

It also, apparently, makes me a lazy, entitled, narcissist who still lives with my parents.

But that’s beside the point. What’s more important about the date of my birth is that it places me at a distinct and pivotal point in human history: I grew up with the Internet — what they call a “digital native.”

I (vaguely) remember when the Internet got popular; having slow, dial-up that made lots of crazy noises whenever you wanted to use it; talking to other angsty teens on AOL Instant Messenger (“AIM”); downloading music on Napster and Kazaa; and then, slowly but surely, having the Internet became engrained in my everyday life as if it was there the whole time.

But, like the bratty sibling I grew up with (upon reflection, I was equally, if not more, bratty — #humility #perspective), I’ve recognized that I have a love/hate relationship with the Internet. It’s a game-changer for the human experience, so, like that sibling, I think I’ll always love it. But, for every positive, innovative element of the Internet there is an equal and opposite reaction.

In an unusually informal video made on a smartphone held by a Pentecostal pastor, Pope Francis called on all Christians to set aside their differences, explaining his “longing” for Christian unity.

The seven-minute video, which was posted on YouTube, was made during a Jan. 14 meeting with Anthony Palmer, a bishop and international ecumenical officer with the independent Communion of Evangelical Episcopal Churches. Italian news reports say that the pope and Palmer knew each other when Francis served as the archbishop of Buenos Aires.

In his remarks, part of a 45-minute video, Francis said, in Italian, that all Christians are to blame for their divisions and that he prays to the Lord “that he will unite us all.”

A few weeks ago, I got one of those viral emails from a guy who shares my interest in Lutheran hymnody — but, most emphatically, not my politics. It linked to a video called “Liberals With Guns!” that claims the shooters at Fort Hood, Columbine High School, Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook and the movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, were all “liberals” and/or “registered Democrats.” It featured “Wild Bill” Finlay, a self-proclaimed “Judeo-Christian values” type of guy wearing a self-satisfied expression and a cowboy hat.

Before hawking a “Wild Bill for America” coffee cup for $14.39 (plus shipping) at the end of the video, Finlay proposes that “every registered liberal Democrat be placed on the mentally ill list, and because mental illness is akin to incompetence, we should consider removing them from certain positions of responsibility. … The liberals of America try so hard to strip others of their rights, perhaps we should give them a taste of their own medicine.”

Ha-ha. Funny guy.

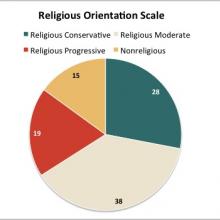

There is a lopsided divide in America about what it means to be a religious person, with a majority believing that it’s about acting morally but a strong minority equating it with faith.

Nearly six out of 10 Americans (59 percent) say that being a religious person “is primarily about living a good life and doing the right thing,” as opposed to the more than one-third (36 percent) who hold that being religious “is primarily about having faith and the right beliefs.”

The findings, released Thursday, are part of a report by the Public Religion Research Institute and the Brookings Institution that aims to paint a more nuanced picture of the American religious landscape, and the religious left in particular.

Lately I have been spending a lot of time reading the book of James. Reading this small yet powerful book has challenged me to think and re-think the very nature and meaning of faith.

I have found it interesting to listen to people speak about faith. Often faith is used to describe what a person believes and does not believe. For example, we might say that we believe in God, Jesus, Allah, Mohammed, Torah, the Bible, the Quran, and so forth. What people say they believe is then equated with their faith. Faith in God means that he or she believes in God. Because I believe in God, I have faith. Faith and belief seem to be synonymous.

This understanding or definition of faith, however, does not seem synonymous with actions or the way we live. Although ideally we believe that faith should affect the way we act, we still speak about faith and action separately. In other words, faith and living out that faith — action — is differentiated and understood separately. For example, it might be possible to have faith, yet not live a life that is based or reflects that faith. It might be possible to have faith in God, even in Jesus, but act in ways that are ungodly or un-Christ-like – participating in violence and war, killing, being inhumane, lying, cheating, being corrupt, and so forth. Although we may act in these ways, and participate in actions that are less than holy, the claim remains that we still have faith. We have faith because we believe in something.

People of faith have long wrestled with the place of faith in the public square. At times religious groups have sought to dominate or control the public square. At other times, they have allowed the state/nation to dominate and control the faith community. Others have sought to distance themselves from the public square – with the Amish being the most distinct example of this. There was a time, a half century ago or more, that mainline Protestantism played a significant role in the public square while evangelicals largely stepped away. In the past three decades the roles have reversed.

The question that is being raised at this time in a number of sectors has to do with whether faith should engage the public square and if so, how should this engagement occur. I have found Mark Toulouse's book God in Public: Four Ways American Christian and Public Life Relate (WJK Press, 2006), to be very helpful in this matter. Mark has a good sense of the relationship between religion and the public square.

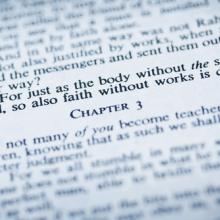

Today is the day we remember the Protestant Reformation. On Oct. 31, 1517 Martin Luther, my denomination’s namesake, nailed his 95 Theses on the church door in Wittenburg. It was the beginning of a new movement that brought many changes to the Christian church. Perhaps the change I am most thankful for (other than a new awareness of justification by faith alone, simul iustus et peccator, and imputed righteousness of course) is that the Reformation paved the way for the Bible to be placed in the hands of the people. Before Luther’s German translation was completed in 1534, which happily coincided with advancements in the printing press, it was virtually impossible for any non-clergy Christians to get ahold of, much less read, the book we take for granted.

Individual faith and the ability to study this book for ourselves is a benefit we don’t even stop to consider. I grew up with more Bibles in my home than we could ever use and have countless different versions now in my office. And yes, there are still some places where access to information and printed text is hard to come by, but at least here, God’s Word is always at our fingertips, if we want it to be.

When people talk about the fall of humanity in the Jewish Genesis story, we never talk much about the Tree of Life. The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil gets all the headlines and sermons because that’s the one that’s supposed to define us. That’s what we see, when we look around at humanity: The Fall, and a lot of evil triumphing over good.

Martin Luther, the father of Protestant churches, “was once asked what God was doing before the creation of the world,” according to German Lutheran theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer. “His answer was that he was cutting canes for people who ask such useless questions.”

Who says you can’t offer a doctrine of abundant grace with a bit of sarcastic wit? For Bonhoeffer, this was really a question of why. Why did God create? What was going on, such that God decided to make a world? As Bonhoeffer saw it, this is a question rooted in guilt, shame, and fear. It’s really asking: What did God want of the world? What did God make me for? Am I living up to it? Am I accepted? It’s a question falling from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, not the Tree of Life.

DURHAM, N.C. — Protestants have traditionally celebrated Oct. 31 as the anniversary of the start of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that divided Western Christendom and gave birth to such diverse religious groups as Lutherans, Presbyterians, Anglicans, and Mennonites.

On Oct. 31, 1517, an Augustinian friar named Martin Luther nailed 95 theses for debate on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, and so sparked a religious reform even he could not control.

But Luther's public life actually began five years earlier, 500 years ago this week, on Oct. 19, 1512, when he finished his formal theological education and was installed as a professor of Bible at a relatively new and still nonprestigious Catholic university in Saxony.

No one, least of all his patrons, expected this soft-spoken young man with a tenor voice and a bubbling sense of humor to turn into a religious bomb thrower, whose theological convictions would alter the religious and political structures of Europe for five centuries. Indeed, no one could have been more astonished by this unexpected development than Luther himself.

If justice is only an implication, it can easily become optional and, especially in privileged churches, non-existent. In the New Testament, conversion happens in two movements: Repentance and following. Belief and obedience. Salvation and justice. Faith and discipleship.

Atonement-only theology and its churches are in most serious jeopardy of missing the vision of justice at the heart of the kingdom of God. The atonement-only gospel is simply too small, too narrow, too bifurcated, and ultimately too private.

Albania was perhaps the most closed society in the world during the Cold War, with absolutely ruthless persecution of all religion. Churches were destroyed in every corner of that country. Clergy were eliminated. Worship was outlawed. And enforcement was brutal.

When Communism fell, and the country opened for the first time in decades, the Albanian church began a miraculous process of rebirth. We heard the moving story of the Albania Orthodox Church, rebuilding countless church structures, but even more importantly, restoring faith in the hearts of its people. I've known its leader, Archbishop Anastasios, from past encounters at the World Council of Churches, and he surely is a saint. The revival of religious faith in Albania and its compassionate service to those in need is a magnificent story of the church's witness, and the Spirit's power.