empathy

WHEN WE THINK OF ART, we usually think of paintings, literature, or film: media that take us outside of ourselves and help us experience a time, place, feeling, or philosophy. Works of art have the potential to move us, sometimes profoundly.

What we don’t think of—not immediately, anyway—are video games. Games are artifacts of pop culture. At best, they’re fun, relatively benign distractions. At worst, they’re violent, desensitizing affairs promoting antisocial behavior. Video games are not, generally speaking, considered transformative or artistically ambitious.

But that might be changing. In recent years, developments in the gaming world covering everything from graphics to narrative structure are changing the low-culture perception of video games, with complex stories that challenge players and sometimes even help them consider the theological.

“Video games are this amazing reflection of how we see the world,” video game developer Ryan Green told Sojourners. “There’s a relationship between the player and the creator of the game that also reflects how we view God. You can see the hands of the designer at any given point.”

Letting love change you

Green and Numinous Games, the production company he co-founded with his wife, Amy, are at the forefront of this movement. They’re the creators behind That Dragon, Cancer, a game detailing the emotional and spiritual journeys of the Greens during their son Joel’s four-year battle with cancer, from which he died at age 5.

That Dragon, Cancer is an empathy game, a video game allowing players to interact and identify with a specific emotional or social experience, with the goal of making the player more sensitive to the issue it presents. In the case of That Dragon, Cancer, the Greens invite players to share their process of hope, doubt, and mourning through a series of interactive vignettes reflecting their experiences during Joel’s illness.

I have been thinking about what it means for me to try to put myself into the shoes of other people, too. When I see someone who is different from me — a transgender person, a Muslim person, a politically conservative person, an 'any kind of different' person — I am tempted to look at that person through a hermeneutic of fear. I either fight against that person or flee from that person. But what if I look at that person through a hermeneutic of empathy? What if I put myself in that person's shoes and walk around? What might happen if I do that?

Listening to faces is hard work and has to be developed slowly over time. We live in a world that teaches us to speak twice as much as we listen, or to speak without listening at all. Yet, over time, listening to faces will grow the most important thing we can have in our hearts — deep empathy for each person we encounter every day.

Working out our salvation and instilling a life of faith in our children isn’t about executing rituals with precision. It isn’t about teaching them to pray eloquently, or to get them to obey without question. It isn’t to give them the letter of the law so they can judge the world with a heavy-handed measuring stick. It is to form and shape their identities into one oriented towards justice and beauty in our world. It is to open their eyes to the realities of oppression and suffering.

In a world where there isn’t enough stickers for everyone in the school, how can we invite the children into the struggle for equality? How do we teach that Jesus wants to give stickers to everyone? If it isn’t good news for everybody, it isn’t good news for anybody. How can we place sticker-sharing to such high priority that it becomes embedded in our children’s psyche, so that kindness is instinctual?

May our children then parallel secular peers in generosity and love. More importantly, may the children of our generation inspire us, the adults, toward greater mercies for the suffering. May love win, justice roll, and the moral arc bend toward the right direction, so we can hold witness to the transformation of communities for good.

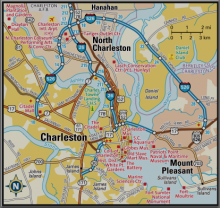

For the past thirty years my family has vacationed in Charleston, S.C. I spent eight years living, going to school, and working in Charleston; I met my wife there, got married there, and it is still a place we count as home when people ask.

The shootings at Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston let loose a flood of memories long shoved into the recesses of my mind. One of these was when I was the youth director for a large white affluent congregation, and the youth groups at Mother Emanuel and my church performed a joint Youth Sunday service in the late 90s.

Driving from Asheville, N.C, to Charleston shortly after the shootings, my heart grew heavy as I wondered what to do when we arrived. Nothing I envisioned captured the heaviness I felt; the need to be useful. I decided to sleep on it.

One question I would ask a blue whale, if I could summon it from the depths of the ocean, would be, "Is it your giant heart that makes your kind the most peaceful and intelligent creatures on Earth?"

I often wonder about the link between the heart and kindness and intelligence. "Cogit ergo sum (I think therefore I am)," wrote René Descartes, and we live in a time where the sum of all of life is the mind, the value of all of life is the ability to be right and to be smarter than anyone else.

But what of "sentimus ergo sumus (we feel therefore we are)?” Is the sum of all of life really empathy, the practice of placing ourselves in the shoes of fellow human beings and walking around in those shoes until we can feel life as they feel it?

"If we value the growth of our hearts most of all, could we be more like you?," I would ask my giant, gentle friend.

For people benefitting from systematic wealth, power, comfort, favor, and convenience, it can be difficult to relate to the constant and endless forms of racism, stereotyping, and injustice that are experienced by others.

The privileged don’t experience the daily realities faced by the likes of Walter Scott, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and millions of others who have lived under completely different — and radically unfavorable — circumstances.

This is why Christians — no matter what your background — must passionately engage in such things as relationship-building, participating in dialogue, and actively reading, experiencing, and listening to various perspectives. Because doing this informs, directs, and edifies one of the most powerful spiritual tools we have: our imagination.

Imagination is defined as the faculty of imagining or of forming mental images or concepts of what is not actually present to the senses.

Friendships, personal accounts, testimonies, books, footage, stories, and experiences empower us to have a better picture, perspective, and understanding of others. Even if we don’t personally struggle with the same types of injustice and inequality that others do, we’re at least given the ability to imagine its reality, accept its existence, empathize with its victims, and comprehend truths we weren’t previously aware of.

In the Bible, Jesus is constantly challenging the status quo and striving for justice, peace, and reconciliation against cultural factors and precedents that seem impossibleto overcome. For the individuals God calls upon, they are required to imagine the inconceivable, accept the unthinkable, and break out of their stubborn paradigms in order to embrace the Divine.

Imagine the sea being parted, walking on water, feeding the 5,000, being healed of leprosy, encountering a talking donkey and a talking (burning) bush, and rising from the dead.

Imagination is defined as, "The faculty of imagining or of forming mental images or concepts of what is not actually present to the senses."

For privileged Christians who have lived the majority of their lives receiving the benefits of systematic wealth, power, comfort, favor, and convenience, it can be almost impossible to conceive of a world where injustice, inequality, and perpetual oppression are daily struggles.

Many privileged believers experience an entire existence completely devoid of the suffering, trials, and endless forms of racism, stereotyping, and injustice that are the daily realities faced by the likes of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and millions of others who have lived under completely different — and radically unfavorable — circumstances.

Thus when parties from both sides try to communicate with one another, it is extremely difficult, frustrating, and nearly impossible to even begin to comprehend each other’s worlds — unless you utilize the spiritual discipline of imagination.

In the Bible, Jesus is constantly challenging the status quo and striving for justice, peace, and reconciliation against cultural factors and precedents that seem impossible to overcome. For the human vessels that God calls upon, they are required to imagine the inconceivable, accept the unthinkable, and break out of their stubborn paradigms in order to embrace the Divine.

Christians often talk about actively changing the world, but too often, we just sit still and passively watch the struggles of others without participating, leading, or caring. We don’t love.

Why? Because many Christians have an inability to use their imaginations.

People who can’t imagine are susceptible to bigotry, racism, hatred, and violence toward others. Why? Because they can’t imagine any other scenario, perspective, or opinion other than their own. They have an inability to see themselves in someone else’s shoes. They can’t see beyond their own narrow reality.

When you can’t imagine, you can’t empathize, understand, or relate with the actions, struggles, pain, suffering, persecution, and trials of others — you become apathetic, unmoved, stoic, and inactive.

Whether our differences are gender-related, age-related, race-related, culturally related, politically related, economically related, socially related, theologically related, value-related, or related to any countless number of factors, overcoming them requires imagination.

When you can’t imagine, you can’t celebrate, appreciate, admire, and joyfully love others. You disconnect yourself from humanity.

I created my SOLE space by providing one desktop computer per four students, a whiteboard to write questions on, and paper and pens for students to take notes for their sharing at the end of SOLE.

Then I asked a big question — “Why does a blue whale have such an enormous heart?” — and I let the adventure begin. My students began their investigations.

After 40 minutes, they shared their discoveries.

“Blue whales swim all over the world,” said Ki’ara, “So they need a gargantuan heart to be their motor.”

“Blue whales can call to each other over almost a thousand miles,” said Heavenly. “They need a big heart to talk to each other.”

“They swim together in pairs,” said Amare, “So they need huge hearts to care for each other.”

“Yeah,” said Isaac, “That’s true … it takes a huge heart to care for somebody.”

“Kids who are nice to me on the playground must have a big heart like a blue whale,” added Aydan. “And people who are mean must have small hearts.”

“Hmmm,” I said. “How can we have big hearts for each other instead of small hearts?”

Strange but beautiful things happen when we begin to identify with people who are culturally different. A few years ago, I became friends with Peter, a guy at my church who also happened to be an undocumented immigrant. One day over lunch, he shared that his mother (whom he hadn’t seen in 15+ years) had recently been diagnosed with a terminal disease. He desperately wanted to visit her, but due to his immigration status, he knew that if he left the U.S. he wouldn’t be allowed to return. Given his obligations to his family in the U.S., Peter made the heart-breaking decision to not to visit his dying mom.

As a U.S. citizen, I hadn’t personally experienced the trials of being undocumented or felt the frustration of geographic immobility while a loved one approached death in a far off land. But throughout my friendship with Peter — getting to know his family in the U.S., listening to him share about the harrowing challenges he experienced on a daily basis, and seeing photographs of his life and family in his home country — I got a glimpse of the world from his perspective. In many ways, Peter’s life was marked by sorrow and loss – and that was more evident than ever during our lunch conversation that day.

I got a glimpse into the politics of scorn this week.

The visual was a photo accompanying a New York Times article on rental properties in Memphis, Tenn. The article itself seemed innocuous, about how foreclosed homes are being scooped up by outside investors and turned into rentals.

The photo, however, was troubling. It showed a young man lazing in a large chair while his two children stared numbly at a television screen and his wife tapped away on a cell phone.

I have no clue into this family’s character. But the visual screamed: “Idle! Lazy!”

In recent weeks, a number of controversial and divisive political questions have dominated the news. Race and voting rights, abortion in Texas, and marriage equality at the Supreme Court have opened anew the scars of old political and cultural wars.

In this conflicted political ambit, the Samaritan's bold compassion is a needed reminder today. Let’s remember to be kind to the stranger, certainly. But just as important is that the story of the Good Samaritan also invites us to imagine ourselves in a different part of this narrative.

Imagine yourself not as the Samaritan seeking to love God and neighbor. Imagine yourself as the person in need. A man on the brink of death. A woman in deepest grief. A man lost in the world. A woman with no hope. Imagine yourself at your most vulnerable, deep in despair with only one hope: perhaps someone will help me.

NOTHING MOVES ME more than a heartfelt tweet. Seriously. Don’t think I’m making fun here. I understand that the Twitter universe (“Twitterverse”? “World o’ Twits”?) is the current preferred method for connecting with the most people in the shortest amount of time. It’s certainly preferable to my generation’s method of communicating, which was to spray-paint the sides of barns.

But if the inspirational tweet is from a member of Congress—taking time away from doing the nation’s business in the most powerful city in the world, depending on where the Koch brothers are living at the time—I can get really choked up.

“My thoughts and prayers are with those in Oklahoma affected by the tragic tornado outbreak.”

Oozing with empathy and originality, this tweet was sent out by Oklahoma Sen. Tom Coburn a few hours after the extreme weather event in May that ravaged the town of Moore. What the tweet did not include—and his office quickly added, lest survivors searching through the rubble for loved ones got the wrong impression—was that the senator would not support federal relief funding unless it was offset elsewhere. If it’s not in the budget, according to Coburn’s long-standing philosophy, it’s not happening.

But let’s be fair: With a tweet you only get 140 characters, so in addition to the words “thoughts” and “prayers,” there’s barely enough room left over to express the important concepts of “freedom,” “liberty,” and “bootstraps,” three concepts people just love to think about when they’re crawling from under what used to be their house. Coburn’s point seems to be that when you’re covered with sheetrock, torn family photographs, and spray-painted sides of barns, the last thing you want is some government bureaucrat arriving with a meddlesome helping hand.

WHEN MY DAUGHTER, Jessica, was 7 years old, some of her best friends had American Girl dolls, so of course she desperately needed one as well. We asked three or four family members to chip in—these were expensive dolls—and got her one for Christmas.

Her doll, “Addy,” came with a story, as did each in the American Girl line. Addy and her mother had escaped from slavery in the American South, and they “followed the drinking gourd” north to Philadelphia, where they were eventually reunited with the rest of Addy’s family. It was a gripping story, especially for a 7-year-old. And the fact that Addy was about my daughter’s age made it all the easier for her to connect.

“It wasn’t so much that I learned ‘facts’” about slavery and race from the Addy stories, Jessica, now 27, told me recently, “but they made it all more personal. Addy was young, like me—I could relate to it.”

Other women who grew up with the dolls echoed that sense of connection with the various American Girl stories. Janelle Tupper, campaigns assistant at Sojourners, was around 7 when she received the “Kirsten” doll, a Swedish immigrant to the U.S. “My most distinct memory from the stories was that, on the boat, her best friend dies of cholera,” Tupper said. “Reading that passage was pretty devastating to me as a kid.” Other books in the American Girl series addressed issues of the day, from child labor to women’s suffrage. And while Tupper said she wasn’t aware as a child of the social justice themes in the stories—“I was just imagining life in the different time periods through the eyes of a character I identified with”—she now sees the series as addressing “societal change in terms that an 8- year-old can understand, often told through the characters’ friendships and family stories.”

By definition, an anesthetic is a drug used to relieve pain (analgesia), relax (sedate), induce sleepiness (hypnosis), spark forgetfulness (amnesia), or to make one unconscious for general anesthesia. Anesthetics are generally administered to induce or maintain a state of anesthesia and facilitate a procedure. I believe that anesthetic can be employed as a striking image for particular deficiencies in faith-based responses to extreme poverty.

As one can cite many examples where faith is proclaimed and practiced solely as an escape from – rather than engagement with – the numerous struggles associated with impoverishment, we recognize that anesthesia is incomplete without corresponding acts of sustainable social surgery.

...

A practical way to serve within the tension of anesthetic and advocate is to experience a small portion of life below the poverty line. The World Bank sets extreme poverty as below $1.50 per day, and I plan to stand in solidarity by attempting to eat on less than $1.50 per day over the course of five days (Monday – Friday).

The announcement was broadcast at the end of the day over the school’s public address system.

"Our Teacher of the Year for 2013-2014 is ... Mr. Barton. Congratulations!"

I walked out into the third-grade hallway where students were lined up for dismissal. Little hands reached up and patted me on the shoulder. Small voices joined together and called out, "We're proud of you, Mr. Barton!" Alondra, a quiet student, pulled me close and said, "Thank you for being my reading teacher." I was honored and humbled.

As I walked back into my classroom, I reflected over my five years teaching at this Title I elementary school. "Who am I, what have I done, to become Teacher of the Year?" I asked myself.

LATELY I’VE been on a campaign to read some of the classic novels that I should have read decades ago. This summer it’s been John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. There, I confessed it. All these years I’ve been coasting on repeated viewings of the John Ford film adaptation. But I’m reading the original now. And despite the hunger and hardship faced by the Joad family, I find myself experiencing nostalgia for those old hard times.

Americans fell into the Great Depression of the 1930s without the safety net of unemployment insurance, food stamps, or federally insured bank deposits. In fact, victims of the current depression have those benefits because of the things their ancestors did 80 years ago. Back then, Americans pulled together with the sure belief that we are all responsible for each other and that no one of us can, or should, stand alone. They recognized that a common plight required common action, and they gave us a trade union movement and a New Deal.

In The Grapes of Wrath, that recognition is rooted in the primary value of family solidarity, which grows to include neighbors and co-workers, and, finally, in Tom Joad’s famous speech, extends to all people struggling for justice (“whenever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat”), and even to all humanity, past and present (“maybe all men got one big soul ever’body’s a part of”).

The impact of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) is experienced with increased intensity as we approach Election Day. Since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that corporations and unions have a First Amendment right to independent political expenditures, certain portions of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act were reversed.

As a result, the voices surrounding political campaigns have risen in strength and size. And so, while a variety of viewpoints exist on the consequences of Citizens United, most agree that it has dramatically altered the culture of U.S. politics, and has thus sparked major discussion on the reach and limits of freedom of speech.

Due to the ramifications of Citizens United, we should indeed recognize and critique the role that freedom of speech holds within a mature democracy. However, as we focus on free speech, the time has come to also consider the contributions of its equally important companion, the responsibility to listen. In other words, as we ponder the primary ingredients of a healthy society, the delicate balance between freedom of speech and the responsibility to listen should be held as a critical priority.

The Ghost of Christmas Past showed Scrooge a total of five visions. It is only the last two which are dark. The first three show the seeds of Scrooges own repentance.

The first vision shown to Scrooge by the Ghost of Christmas past is that of a young Scrooge reading alone, neglected by his peers, just before Christmas. Scrooge, watching his old self, begins to cry.

“What’s the matter?” asked the Spirit.

“Nothing,” said Scrooge. “Nothing. There was a boy singing a Christmas Carol at my door last night. I should have given him something: that’s all.”