blues

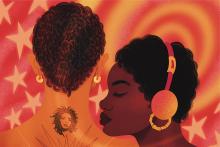

MUSIC IS MY safe space. When all hell is breaking out, I can put in my AirPods and turn on part of the soundtrack of my life and reset. The pandemic created a chronic hell that illuminated oppressive forces that have existed for centuries. Music became even more essential for my survival.

I am a Black clergywoman who is clear that “my emancipation doesn’t fit” many people’s equation. Let me say that another way: My authentic expression of self makes some people uncomfortable. My unapologetic expression of womanist Blackness often sheds light in the shadows of a corrupt world.

I won’t pretend that I have always felt free to be me. It took a pandemic to give space to be reminded by theologian and prophet Lauryn Hill that “deep in my heart, the answer, it was in me.” Hill’s lyrics and very existence compelled me to “[make] up my mind to define my own destiny.”

Some consider Hill to be one of the greatest lyricists of all time. An eight-time Grammy winner (with 19 nominations), she sings, raps, and acts. She is hip-hop royalty. In the ’90s, I wanted to be her. She wore the dopest locked hair style, had the most beautiful brown skin, and expressed her Blackness with boldness and class. She had, and still has, a lyrical flow that men and women couldn’t ignore. She was fly. (Translated as cool, sexy, smart, and stylish.)

Her industry-shaking debut solo album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, released in August 1998, will stand the test of time. Hill speaks truth in ways that penetrate the soul. I was a young mother when the album came out. She articulated things that only a Black woman could identify with. She spoke of the tension and beauty of having a child when society was telling her that motherhood and a career couldn’t coexist. She sang and rapped about self-respect, love gained, and love lost. This album is life. This album ministers. This album is sacred.

IT'S ALMOST DECEMBER, and in a few weeks we may gather with our families (potentially via Zoom) to sing “Away in a Manger” and “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing.”

Each of these songs depicts baby Jesus in a different way, from a poor, defenseless child to a newborn king. Each contributes to our faith in a different way. That tiny baby reminds us of Jesus’ humanity and his solidarity with the poor, while the incarnated Lord reminds us of God’s splendor and glory.

From these hymns to the latest Hillsong chorus, most songs about Jesus have been written by Christians for their fellow believers. Over the past 50 years, however, this has changed. Songs about Jesus no longer show up just in church, but also in discos, honky-tonks, blues bars, and strip clubs. Over the past 50 years, Jesus has appeared in hundreds of songs in every secular genre. These artists explore in their own unique ways the question that Jesus asked his disciples: “And who do you say that I am?”

[Editor's note: This article is adapted with permission from Otis Moss III's book Blue Note Preaching in a Post-Soul World: Finding Hope in an Age of Despair, published by Westminster John Knox Press, 2015.]

IF WE ARE to reclaim the best of the preaching tradition, then we must learn what I call the blue note gospel. Before you get to your resurrection shout, you must pass by the challenge and pain called Calvary.

What is this thing called the blues? It is the roux of black speech, the backbeat of American music, and the foundation of black preaching. Blues is the curve of the Mississippi, the ghost of the South, the hypocrisy of the North. Blues is the beauty of bebop, the soul of gospel, and the pain of hip-hop.

Before we can speak of the jazz mosaic or the hip-hop vibe for postmodern preaching, we must wrestle with the blues. In his song “Call It Stormy Monday,” T-Bone Walker laments how bad and sad each day of the week is, but “Sunday I go to church, then I kneel down and pray.”

Walker’s song unintentionally lifted up the challenge that the blues placed before the church and that black religiosity still seeks to solve. “Stormy Monday” forces the listener to reject traditional notions of sacred and secular. The pain of the week is connected to the sacred service of Sunday. There is no strict line of demarcation between the existential weariness of a disenfranchised person of color and the sacred disciplines of prayer, worship, and service to humanity.

This blue note is a challenge to preaching and to the church. Can preaching recover a blues sensibility and dare speak with authority in the midst of tragedy? America is living stormy Monday, but the pulpit is preaching happy Sunday. The world is experiencing the blues, and pulpiteers are dispensing excessive doses of non-prescribed prosaic sermons with severe ecclesiastical and theological side effects.

The church is becoming a place where Christianity is nothing more than capitalism in drag. In his book Where Have All the Prophets Gone? Marvin McMickle, president of Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School, asks what happened to the prophetic wing of the church. Why have we emphasized a personal ethic congruent with current structures and not a public theology steeped in struggle and weeping informed by the blues? McMickle’s book is instructive for us. He demonstrates the focus on praise (or the neo-charismatic movements) coupled with false patriotism—enhanced by the reactionary development of the tea party, the election of President Barack Obama, and personal enrichment preaching (neo-religious capitalism informed by the market, masquerading as ministry).

The blues has faded from the Afro-Christian tradition, and the tradition is now lost in the clamor of material blessings, success without work, prayer without public concern, and preaching without burdens. The blues sensibility, not just in preaching but inherent in American culture, must be recovered. We must regain the literary sensibility of Flannery O’Connor, Zora Neale Hurston, Ernest Hemingway, and James Baldwin; the prophetic speech of Martin Luther King Jr., William Sloane Coffin, and Ella Baker; along with the powerful cultural critique of Jarena Lee and Dorothee Sölle.

The blues, one of America’s unique and enduring art forms, created by people kissed by nature’s sun and rooted in the religious and cultural motifs of West Africa, must be recovered. The roots are African, but the compositions were forged in the humid Southern landscape of cypress and magnolia trees mingling with Spanish moss. It is more than music. The blues is a cultural legacy that dares to see the American landscape from the viewpoint of the underside.

THE DEATH of B.B. King this spring was marked by an outpouring of homage appropriate to the man’s talent, his influence on U.S. culture, and his fabled personal humility and generosity.

He started out picking cotton and singing on the street and ended as one of the most famous and honored men on earth—a classic rags-to-riches tale. But King wasn’t just a black Horatio Alger. And his story wasn’t just one of individual striving and achievement. King also understood that his art was rooted in the collective struggle of his people and that he was a part of that struggle.

I grew up about 30 miles from B.B. King’s Sunflower County, Miss., home, but I discovered him the same way most white people my age did, by hearing “The Thrill Is Gone” on the radio. It’s a recording that still jumps out of the speakers and grabs the heart. It starts with a mournful guitar melody. Then, behind verse two, an eerie, quavering wash of strings begins low in the mix and rises through the rest of the song. By the time King wails out to his lover, “I’m free from your spell, and now that it’s all over, all I can do is wish you well,” you knew you were hearing the last words of a dying man.

AN OLD Buddy Guy song is titled “First Time I Met the Blues.” I don’t remember the first time I met the blues, but I do remember that I was captivated by the music. For many years now, two of my passions have been listening to blues and studying the Bible. Gary W. Burnett, a lecturer in New Testament at Queen’s University in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and an amateur blues guitarist, shares those passions. This book, he writes in the introduction, is his attempt “to combine in some ways these two passions and to be able to reflect on Christian theology through the lens of the blues.” He succeeds with a well-crafted synthesis of U.S. history, African-American history, the blues, and New Testament scholarship.

Blues music is one of the great contributions of African-American culture to the U.S. While rooted in the oppression of slavery and post-slavery Jim Crow, it speaks meaningfully to the experience of all people. It’s a music that grabs your soul and won’t let go. And Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount is central to his message of life in the coming and present kingdom of God. It can also grab your soul and not let go. By juxtaposing blues lyrics with passages from the Sermon, Burnett shows the common themes that emerge.

INSIDE TOWN HALL, New York’s legendary concert venue, the dusty twang of a harmonica slices through the low din of the crowd filling the 1,500-seat auditorium. Most are likely here for the headliner, singer-songwriter Patty Griffin, who will take the stage after this, a performance by her opening act, Parker Millsap.

The bluesy riffs from Millsap’s harmonica are intense, long and wailing, before fading into the slow, dirty licks of a slide guitar. Then a voice, old and soulful, throbs through the room, crying out the first line of the old gospel standard “You Gotta Move” and shocking many in the audience, residents of a city where very little is shocking. You can see the wave of surprise move like a serpent across the room, with people turning to their companions, eyebrows raised and a whisper on their lips.

It’s the age that gets them—the man standing at center stage, flanked by two bandmates and looking like a rockabilly idol, with his gelled quiff and rolled-up shirt sleeves, isn’t the 60-year-old blues singer he sounds like. No, he is baby-faced, young—barely even 21—and yet he’s pulling this song from some secret, battered place inside him that’s far older than his years, and matching it with a sensual intensity that sizzles in the audience. By the time Millsap allows the last note from his weathered voice to fade, he has commanded the undivided attention of one of the world’s toughest crowds.

And they are raring for more.

The girl with the mobile garden dress -- cover songs by Iron & Wine -- kid reacts to first sip of root beer -- art from wine stains -- and Conan teaches first-graders how to sing the Chicago blues. See these in today's Links of Awesomeness...

It’s good to start a new year by remembering those who passed in the just concluded year. These aren’t the most famous (or infamous), and I didn’t know them personally (or, at best, had met several briefly), but their lives touched mine in three of my passions: American roots music, politics and public life, and baseball.