The early seasons of Stranger Things hit different in 2025. I realized this as I rewatched the series ahead of the final season’s premiere. Watching federal agents sow mistrust and harm children no longer seems like a sci-fi nostalgia trip, and the creeping evil influence of the Upside Down feels more like commentary on current events than a Stephen King pastiche. In fact, in fighting for the world they want and practicing radical solidarity, the kids in Hawkins, Ind., teach us exactly the lesson we need for right now. Stranger Things might even be a modern-day parable.

When the show debuted in 2016, it was a smash hit and proved that Netflix could compete in the original-content arena. Following a group of teenagers and the adults they trust in a fight against the forces of evil, the show owes much of its success to ’80s nostalgia. The group has fought various monsters over its seasons, many of which took cues from Dungeons & Dragons, but Season 4 took a more psychological turn, focusing on a being that feeds on the ongoing trauma people in Hawkins have experienced in their personal lives.

As the Apostle Paul warns us in 1 Timothy 6:9: “But those who want to be rich fall into temptation and are trapped by many senseless and harmful desires that plunge people into ruin and destruction.” And if you want proof of Paul’s words, look no further than the release of Jeffrey Epstein’s emails.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration has ordered a broad review of all refugees who entered under former President Joe Biden, an internal U.S. government memo seen by Reuters said, an unprecedented move that could reopen cases of thousands who sought U.S. protection.

The order would apply to about 233,000 refugees who entered between Jan. 20, 2021 and Feb. 20, 2025, according to the memo signed by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Director Joe Edlow. It also orders a halt to all processing of applications for permanent residence for refugees who entered under Biden.

The most powerful moment in Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery isn’t a murder or a big reveal. It’s a phone call.

Father Jud Duplenticy (Josh O’Connor) is trying to help solve the murder of the controversial head priest of his small-town parish, Monsignor Jefferson Wicks (Josh Brolin). Standing in the rectory with private detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig), Jud calls a records office to request information related to the case. The clerk, Louise (Bridget Everett), is overly chatty, much to Father Jud’s annoyance. It seems like she’ll never shut up. But it turns out she, too, has a request. After a few minutes, Louise stops talking to ask, “Father, would you pray for me?”

What if Jesus used his omnipotence not only to curse barren fig trees but also to kill those who annoyed him?

That’s a premise director Lotfy Nathan explores in The Carpenter’s Son. The supernatural horror film imagines Mary, Joseph, and Jesus’ time in Egyptian exile after they flee King Herod (though curiously, none of the characters in the film are directly called by those names). Nicolas Cage plays the Carpenter, who, along with the Mother (FKA twigs), tries to protect their son (played by Noah Jupe, credited only as The Boy) from the suspicious townspeople around him. The Boy’s miracles are awe-inspiring, but they’re also terrifying: In one sequence, he pulls a snake out of a woman’s mouth. While the Carpenter and Mother try to control the Boy’s power, they’re not able to stop his wanderings. Eventually, his curiosities lead him to a devil figure—a character known only as the Stranger (Isla Johnston), who tries to use his powers for her own ends.

In early November, Democrats won several key elections up and down the ballot in states like Virginia, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and, perhaps most notably, in New York, where Zohran Mamdani became the first Muslim, South Asian, Democratic Socialist mayor-elect in New York City’s history. For voters concerned about the Republican Party’s authoritarian lurch, it was a reminder that political wins on the left are still possible.

Let’s take a quick trip back to the fall of 2016. Justin Bieber, Drake, and Twenty-One Pilots are topping the charts. All the cool kids are bottle-flipping. And almost every adult I know is falling in line to vote for Donald Trump. I’m from the western side of Michigan, and my home county went to Trump by almost 30 percentage points.

I was just starting to develop political opinions at that time, but it shocked me how so many people—who I knew cared deeply about their own moral lives—could countenance voting for a candidate who made a mockery of Christian values like forgiveness and marital fidelity.

On Nov. 14, more than 100 clergy gathered to raise their voices to demand the closure of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement processing facility in Broadview, Ill., the release of all detainees, and that the Department of Homeland Security honor federal law by allowing detainees spiritual care.

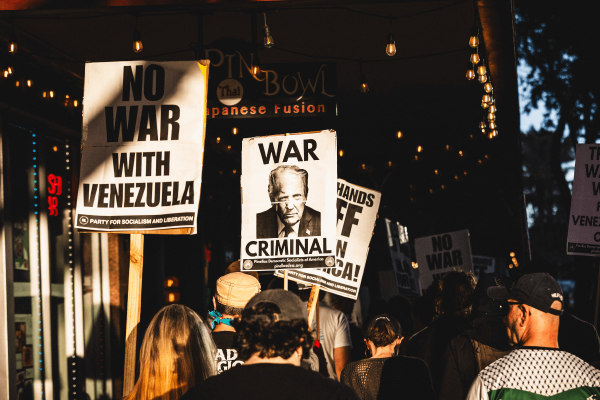

The Trump administration is blowing boats to pieces off the coast of Venezuela.

At different points this year, I’ve been left with the unsettling feeling that I don’t have the emotional bandwidth to fully process—let alone respond to—all of what’s happening. Early in the year, we all acknowledged that this overwhelmed feeling was by design, part of the Trump administration’s “flood-the-zone” strategy, intended to weaken and divide its opposition.

I’ve been wrestling with this in light of the attacks the Trump administration is orchestrating in Venezuela. On one hand, I’m perplexed at why such a costly, unlawful, and frankly evil operation isn’t garnering louder public outcry; on the other hand, I know there is so much else on people’s minds. It’s not that we don’t care about it all—from Chicago to Palestine to Sudan to so many other places where we know there’s urgent suffering—but there’s only so much outrage we can process before weariness takes over.

And yet I can’t ignore what’s happening in Venezuela

On the cover art of her latest album, Lux, Spanish superstar Rosalía poses in a white nun’s habit, arms bundled to suggest straight-jacket confinement or maybe self-love. Before anyone heard a note of the new music, the internet was already bubbling over with commentary, par for the course when it comes to the complicated pop auteur. Fans and haters alike wondered what the Catholic imagery might mean. Habit aside, had Rosalía gone tradwife? Even Ikea joined in on the pre-release conversation, posting a version of the album cover with an overhead lamp. In Latin, Lux means light.

The album is a visionary landmark in pop music. Largely departing from previous forays into flamenco fusion and experimental reggaeton, Rosalía primarily draws from the classical tradition for the project, recording with the London Symphony Orchestra and pushing her voice into new operatic territory. Oh, and she sings in 13 different languages.