Lynch, who died this month days before his 79th birthday, was fascinated by the coexistence of light and dark in the world, the effects of our sinful impulses on others, and what can happen when we pursue what’s right.

But before her sermon concluded, Budde addressed the president directly:

“Let me make one final plea, Mr. President: Millions have put their trust in you, and as you told the nation yesterday, you have felt the providential hand of a loving God. In the name of our God, I ask you to have mercy upon the people in our country who are scared now. There are gay, lesbian, and transgender children in Democratic, Republican, and independent families, some who fear for their lives.

A favorite movie of mine growing up was the 1999 cartoon Our Friend, Martin. It combines two of the subjects I love most: time travel and Martin Luther King Jr. The main character, Miles, a Black sixth grader, visits the childhood home of King and ends up traveling back in time to meet King at various stages of his life. Miles, who was largely unaware of King before time traveling, eventually learns that King was assassinated. In order to prevent this, Miles convinces his new friend Martin to come to the future with him. And while that decision spares King’s life, the movie makes it clear that Miles saving his friend’s life would prevent the racial equality we now enjoy in the U.S.

In the modern U.S., are we really enjoying a post-King racial equality?

President Donald Trump’s inauguration as the 47th president was filled with religious imagery that often projected God’s blessing on Trump’s promises of American domination, expansion, and nationalism.

Rev. Robert W. Fisher, the rector of the church, told Sojourners in an email before the service that the church was making a concerted effort to return the service to its traditional roots. “The service is meant to be centered on God and humility before the almighty, and to be a call to ‘the better angels of our nature’ for those who are entering into a new season of service,” Fisher wrote in an email.

As images from the cataclysmic firestorms engulfing Los Angeles County emerged, one word came up consistently in the captions: apocalyptic. The devastating effects of unusually wet winters followed by record-dry foliage and the incendiary whip of Santa Ana winds created the conditions for what Sammy Roth, the Los Angeles Times’ climate columnist, called “apocalyptic infernos.” But for faith and justice leaders in LA, the fires were apocalyptic in another way.

As we enter a second Donald Trump presidency, the stakes could not be higher for undocumented people and asylum seekers in this country. Having promised mass deportations to a degree never attempted in the United States, President-elect Trump’s new border czar, Tom Homan, has signaled that the administration’s cruelty will begin in my backyard — Chicago. What he might not be counting on is organized resistance from labor, faith, and immigration leaders that will attempt to thwart these plans.

The juxtaposition is hard to ignore: President-elect Donald Trump, who launched his political career by questioning — without evidence — the citizenship of our country’s first Black president, will take his second oath of office on the day we remember and honor Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., this country’s greatest champion for civil and human rights. Though I hope and pray Trump’s second term will follow the moral vision we honor every year on King’s birthday, I fear the dream King cast for America is much more akin to Trump’s nightmare.

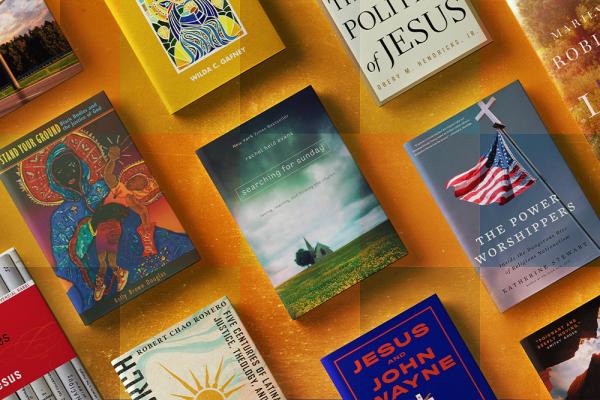

Since our earliest issues, Sojourners has maintained that culture coverage is just as much a part of our mission to articulate the biblical call to social justice as news stories and commentaries. And after reviewing the list below, we suspect you’ll see why. The books on this list span many genres, but they all circle the same core question: What does our faith call us to do in the face of injustice?

Israel and Hamas agreed to a deal to halt fighting in Gaza and exchange Israeli hostages for Palestinian prisoners, an official briefed on the deal told Reuters on Wednesday, opening the way to a possible end to a 15-month war that has upended the Middle East.