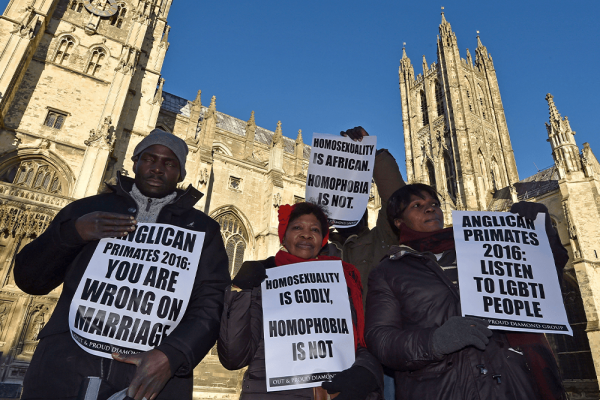

The Church of England will refuse to allow same-sex couples to get married in its churches under proposals set out on Wednesday in which the centuries-old institution said it would stick to its teaching that marriage is between a man and a woman.

Christians need better analytical tools that can help us parse out the systems of global exploitation. These systems keep us from loving our neighbors from every nation, which is a central emphasis of the gospel. For example, investigating who is producing the products we buy and under what labor conditions they work can show us where our neighbors are hurting and how we’re implicated.

King’s preaching used the power of language to interpret the gospel in the context of Black misery and Christian hope. He directed people to life-giving resources and spoke provocatively of a present and active divine interventionist who summons preachers to name reality in places where pain, oppression and neglect abound. In other words, King used a prophetic voice in his preaching — the hopeful voice that begins in prayer and attends to human tragedy.

Listen to the trailer for Lead Us Not, a new podcast from Sojourners hosted by Jenna Barnett.

During his recent visit to the U.S.-Mexico border, President Joe Biden announced changes to border enforcement and the asylum process — the legal process that allows people fleeing danger to seek safety in the U.S. One of the most concerning changes was an expansion of Title 42, a public health policy invoked by former President Donald Trump that weaponized the pandemic to turn away many Black and brown migrants looking for asylum.

Late last week, the White House announced new enforcement measures at the U.S.-Mexico border. Among other things, these measures expand the pathway for migrants from Haiti, Cuba, and Nicaragua to receive two years of legal entry if they have an eligible U.S. sponsor — and allow the administration to expedite removal of migrants from these nations who cross into the U.S. from Mexico without documentation. It’s unclear what the full human impact of these measures will be, but when I read the news, my heart broke for those whose pathway to safety just slipped even further out of reach.

In the immediate aftermath of Jan. 6, 2021, I naively believed that the violent attempt to overturn the 2020 election outcome would serve as a breaking point for the nation and the Republican Party. Despite the party’s anti-democratic slide, including so many embracing the lie that the 2020 election was stolen, I thought the collective horror of the day — felt across the political spectrum — would awaken everyone to the danger that former President Donald Trump and his enablers posed to our democracy. Of course, we now know that isn't what happened.

Former Pope Benedict, who in 2013 became the first pontiff in 600 years to resign, died on Saturday at age 95 in a secluded monastery in the Vatican where he had lived since stepping down.

Black Dignity is a must-read for anyone struggling against domination in a world constituted by anti-Blackness. For Lloyd, domination is the arbitrary exertion of one’s will over another, and its “primal scene” is the master/slave relation. For Lloyd, his use of the language of “domination” points toward a specific kind of relation that permeates the world: anti-Black violence. Lloyd specifically says the purpose of the book is “to get a sense of this new language of Black dignity, to explore how the hashtags could be filled out, linked together, and oriented toward the struggle against domination in general and anti-Blackness in particular.” Morally stimulating, energizing, probing, and clear, Black Dignity demonstrates Lloyd’s ability to weave together and synthesize Black political and religious thought.