Born Again opens by bringing back the central members of the Netflix series cast, including Charlie Cox as blind lawyer Matt Murdock, Elden Henson as his best friend and partner Foggy Nelson, and Deborah Ann Woll as his love interest and other partner Karen Page. Within minutes, they’re attacked by the super-assassin Bullseye (Wilson Bethel) and Matt changes into Daredevil to fight back. But he’s not quick enough to stop Bullseye from killing several innocents, including Foggy. After Matt tries to kill Bullseye in retaliation, he decides to put his vigilante days behind him and seek justice through the law instead of through fighting on rooftops.

To put it another way, Matt decides that vigilantism has failed and it’s time to put his faith in the law. Yet, each episode of Born Again has put that faith to the test — with decidedly mixed results.

At Lane Murray, where I’m incarcerated, a bureaucratic rule creates a peculiar dilemma for someone like me who finds truth and solace in both Christianity and Buddhism. The prison system demands I choose just one, but my soul refuses to be so neatly categorized. We’re also only allowed to change our religious affiliation once every six months. As if divine inspiration could ever follow an administrative calendar.

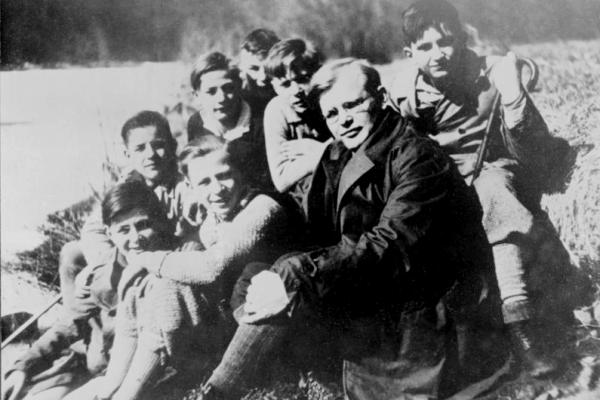

The German pastor was executed by the Nazi regime at Flossenbürg concentration camp on April 9, 1945, just two weeks before the United States liberated the camp. When he died he famously remarked to another prisoner, "This is the end — but for me, the beginning."

Alissa Wilkinson, a movie critic at The New York Times and a Didion expert, is especially interested in how Hollywood continues to use such cliches when telling stories. Her newest book, We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion in the American Dream Machine, is an exploration of Didion’s writing in connection to the movie business and how her observations about Hollywood can help us interpret the current political landscape

The pope’s final months have felt to me like the times when my grandparents were at the end of their lives. We waited for updates from the doctors. We waited with dread for the phone call — or in this case, breaking news emails and social media posts — to bring the final news. There were moments of hope, including Pope Francis emerging from the hospital and appearing in St. Peter’s Square. But we knew that at some point, we’d be facing the loss of someone we loved.

Pope Francis, born Jorge Mario Bergoglio in Buenos Aires, Argentina, was the first in a long line of 266 popes to be from South America and the first born outside of Europe since the 8th century. The pope, also the first to be a member of the Jesuit Order, was beloved by many progressive Catholics and lauded for his priorities of uplifting marginalized communities, protecting immigrants and advocating for environmental justice. According to a 2024 Pew Research Center survey, about 75% of U.S. Catholics viewed Pope Francis favorably.

But he was also a polarizing figure. He struggled to manage the ongoing sexual abuse crisis that plagued his predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI. Pope Francis met with survivors and attempted to pass reforms within the Church, but victims continue to come forward.

In his 12 years as pontiff, Pope Francis forged a legacy of compassion, humanity, and joy. The pope’s concern for social justice was on the mind of many mourning his death. From climate change to global poverty, war and violence, LGBTQ+ people and women’s roles in the church, Francis was remembered not just for his teachings or leadership on hot-button topics, but also the Argentine’s pastoral approach to the people caught up in them.

Francis’ attempts at reforming the church often clashed with Catholicism’s growing right wing and failed to stop the flood of Catholics abandoning the church. It takes time to turn a 2,000-year-old church around, and ultimately, Francis’ papacy would be a complicated one, marred by the damage done in the church’s past, even as he tried to guide it forward into an unclear and troubling future. But like his namesake saint, he always put being a pastor first.

Francis called the church hours after the war in Gaza began in October 2023, Antone said, the start of what the Vatican News Service would describe as a nightly routine throughout the war. He would make sure to speak not only to the priest but to everyone else in the room, Antone said.

An old Italian saying warns against putting faith, or money, in any presumed front-runner ahead of the conclave, the closed-door gathering of cardinals that picks the pontiff. It cautions: “He who enters a conclave as a pope, leaves it as a cardinal.”

But here are some cardinals who are being talked about as “papabili” to succeed Pope Francis, whose death at the age of 88 was announced by the Vatican on Monday.