Bill Wylie-Kellermann is a retired Methodist pastor, nonviolent community activist, teacher, and author. His next book is forthcoming this summer: Celebrant’s Flame: Daniel Berrigan in Memory and Reflection (Cascade, 2021).

Posts By This Author

What Do You Do When Sacred Vows Defy Church Doctrine?

Reflections on a forbidden wedding in a time of denominational divide.

IN AUGUST, LEADERS of the United Methodist Church from around the world are scheduled to meet, in Minneapolis and/or online. The denomination’s future will be on the table as delegates address the decades-old debate about full inclusion of LGBTQI members, including in same-sex marriage and ordination. Meanwhile, congregations around the U.S. and elsewhere have taken various approaches to the pastoral realities of their members. Lydia Wylie Kellermann and her father, retired Methodist pastor Bill Wylie-Kellermann, explain what it meant to support each other through Lydia’s wedding and the ecclesial reverberations that followed. Editor's note: After this issue went to print, the UMC postponed the 2021 General Conference until 2022.

Lydia Wylie-Kellermann: This is a story about risk and fear. It is a story about love. And it’s about the moments when standing beside the ones you love becomes an act of justice. It is the kind of story that begs us to ask what it means to be church. It is an ordinary story turned holy by the common occurrence of the very personal moments of our lives interacting with structural injustice and the way resistance and love unfold.

Ten years ago, I married Erinn. It was in a political moment when gay marriage was illegal and most denominations were still forbidding it.

Yet we were clear that we were not merely roommates or partners, but that marriage was a vocation we were summoned to together. We had no doubt that our relationship was blessed by community and by God. We wanted to promise our lives to one another and publicly offer our marriage as a gift back upon community.

It was a moment of total clarity for me, yet it was also really scary. We had to climb the steps of the church fearing we would pass through a line of protesters. We entered the sanctuary feeling the loved ones missing in the pews because they couldn’t support our marriage. We walked hand in hand down the aisle, combatting our own internalized homophobia, showing our love publicly with hands, promises, and kisses.

We could not have done it without the love of community. The dearly beloveds who filled that church held our hearts and knees steady.

One of those people that stood beside us and laid his hands upon us was my dad. He loved us, celebrated us, and summoned God to move in and through the day and into the rest of our lives. He co-officiated our service. As an ordained Methodist pastor serving a spunky, activist Episcopal church, he was risking losing his orders and losing his job.

Bill Wylie-Kellermann: Those were real fears. For as long as I can remember, I had said to myself that if a member of my congregation asked me to preside at a same-sex wedding, one discerned in pastoral care, that I would certainly do it. I was navigating a contradiction in the United Methodist Book of Discipline that enjoined me to offer pastoral ministry to all members in my care but a couple of paragraphs later forbade me to offer sacramental care to particular parishioners. This marriage was essentially pastoral work, but one that functioned as a public action of civil and ecclesial disobedience. I took comfort in Jesus’ ministry, where a personal act of healing would publicly violate Levitical laws of purity, say, putting him in trouble.

Tracked But Not Seen: The Fight Against Racist Surveillance

In Detroit, the constant flash of green lights says: You are being watched.

WE GATHERED THIS fall on the steps of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church. Summoned by the Detroit chapter of Black Youth Project 100, we were preparing to march a mile-long stretch of gentrified Michigan Avenue, which intersects there. I had served the church for 11 years as pastor, and in the last dozen or so this Catholic Worker neighborhood had been invaded by $400,000 condos, plus destination bars and restaurants. Among others, guests at our Manna Meal soup kitchen and Kelly’s Mission, largely black, are stigmatized and made unwelcome.

But the focus of the march was more than the gentrified influx: Accompanying gentrification has been a heavy increase in electronic surveillance by the so-called Project Green Light, where businesses pay for street cameras that feed to a Real Time Crime Center deep in police headquarters. In areas like this, as with downtown, high surveillance makes white people feel safe for moving in or just shopping and dining.

Dan Gilbert, a mortgage, finance, and development billionaire, owns more than 100 buildings downtown, all covered with the cameras of his own Rock Security. They feed to his corporate center, but also to the police crime center. Detroit Public Schools has its own central command, which is not yet tied to the police center. Likewise, a separate system of streetlight cameras, and even drones, is under development. California recently banned the use of facial recognition software in police body cams, which would convert an instrument of police accountability into a device of surveillance. Michigan has not.

Most Project Green Light cameras are in Detroit neighborhoods, on gas stations, bars, party stores, churches, and clinics. There, each is marked with the constant flash of green lights that say: You are being watched. When the city demolished a house behind ours, we had to hang light-impervious curtains to prevent green pulsing on our bedroom wall from the funeral home a block away.

For nearly two years, unacknowledged, facial recognition software was being employed by the police department. The software can be used with a “watch list” of persons of interest, plus access mug shots, driver’s license and state ID photos, and more—perhaps 40 million Michigan likenesses. A string of recent studies indicates the software can be inaccurate for dark-skinned people, creating false matches and prosecutions. A federal study released in December, according to The Washington Post, showed that “Asian and African American people were up to 100 times more likely to be misidentified than white men.” Thus, resistance to the system quickly mounted in Detroit, which is 80 percent black.

There are two surveillance-industrial complexes. It’s said the days are coming when nations will need to choose which surveillance network to join, the American or the Chinese version—parallel to military alliances. China has 200 million cameras focused on its people, but with 50 million, the U.S. has more cameras per capita. The best facial recognition technology is coming out of Chinese firms, but these are banned in the U.S. because of their connection to “human rights abuses.” The Detroit contract is with DataWorks Plus.

Orwell would be astonished

THE BLACK YOUTH PROJECT 100 march along Michigan Avenue was more like a dance parade, thick with drums, rhythm, and chant: “Black Out Green Light.” This stretch is a so-called Green Light Corridor, where all businesses participate, marked with modest and tastefully lighted signs. At each venue we passed—coffee house, bar, restaurant, bagel shop—three or four folks would go inside with signs and leaflets to chant and speak. A nonviolence training a couple weeks prior had prepared participants for the increasing police presence as the action proceeded. Squad cars blared sirens and officers stood by doorways, never blocking entrance, but threatening. Back at the church Rashad Buni of BYP100, which seeks “Black Liberation through a Queer Feminist Lens,” called for surveillance funds to be spent instead on neighborhood investment—foreclosure prevention, job training, clean affordable water—as the real source of community security. We all want safe neighborhoods. The question he puts is: By what means?

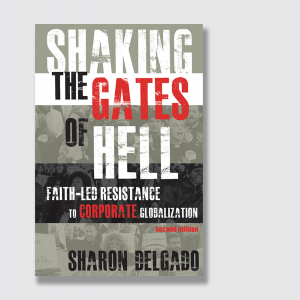

An Updated Look at the Global Economy vs. Jesus

A review of "Shaking the Gates of Hell: Faith-Led Resistance to Corporate Globalization, Second Edition," by Sharon Delgado.

JESUS HAS THE first word in Shaking the Gates of Hell: his warning against serving Mammon as master. We are on notice that this book on analyzing and resisting the assaults of global economy will do so by way of biblical spirituality. To put it more precisely, Sharon Delgado’s critique will rest on a foundational theology of the principalities and powers.

The book begins in a jail cell, where she was in lock-up following arrest in 1999 as part of the massive demonstrations known as the Battle in Seattle, which effectively shut down meetings of the World Trade Organization. Shake those gates. Rooted in action, prayers in such places can seed entire volumes. Also to say: This book is punctuated with personal stories, pastoral and political.

That Fortress Press has seen fit to publish this updated edition is testimony to its staying power as a substantive primer. There are new sections on “algobot” market investing, racial profiling, mass incarceration, and the path to permanent war. Climate predictions that seemed dire in the first edition already need to be updated, as timelines shorten and catastrophic realities set in.

Structurally, the first third of the book focuses on “the undoing of creation” (a phrase of William Stringfellow’s defining “the fall”). Much of that is devoted to the wounds of Earth, and then to human wounds by toxification, technology, impoverishment, and violence.

Rooted in Exile

We’ve been sent a letter from Jeremiah, wherein lies a future with hope.

It’s always tempting to read without context, or to quickly presume our own. In which case this might yield a bumper sticker for urban ministry: Seek the Welfare of the City. Or some universal and individual dictum of God’s love.

But time and place are crucial to interpretation. This one, from the prophet Jeremiah, was penned in the reign of King Zedekiah, between the first Babylonian invasion of Jerusalem in 597 B.C.E. and the final destruction of Jerusalem and temple in 587, with a second deportation. It is a letter sent to the exiles by way of the king’s official couriers. The location of the letter is betwixt and between. Written in Jerusalem, read in Babylon. For that matter, kind of like our situation.

So, from where do we read? Equally crucial to know. William Stringfellow, in his An Ethic for Christians and Other Aliens in a Strange Land, put it like this:

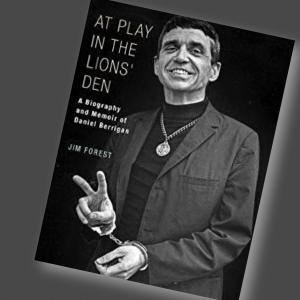

An Unbound Spirit

At Play in the Lions' Den: A Biography and Memoir of Daniel Berrigan, by Jim Forest. Orbis Books.

WHEN DANIEL and Philip Berrigan, A.J. Muste, John Howard Yoder, and a handful of Catholic radicals gathered in 1964 with Thomas Merton at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky for a retreat concerning the spiritual roots of protest, the intercessions of that meeting, I am convinced, not only seeded a movement but summoned my vocation.

Four years later when Daniel and Phil Berrigan and seven others entered the draft board in Catonsville, Md., removed 1A files and burned them with homemade napalm, those ashes too would eventually anoint my pastoral calling. October marks the 50th anniversary of the trial of the Catonsville Nine. Released in February 1973 after 18 months in the federal penitentiary at Danbury, Conn., Daniel Berrigan came to New York and taught the Apocalypse of John when I was a student at Union Seminary. Full disclosure: He became to me not merely teacher, but mentor and friend.

In the year following Dan’s death (April 30, 2016), Jim Forest undertook the heroic literary effort of writing At Play in the Lions’ Den. Perhaps he had a running start. Three things of note up front. One is that Forest’s own life is inextricably tangled with Berrigan’s. He was, for example, editor of The Catholic Worker when Dan first appeared there, was part of the 1964 retreat with Merton, and responded to Catonsville by joining others in a draft board raid in Milwaukee within the year. So, like the Acts of the Apostles, there are whole sections of this book written in the first-person voice. Or betimes, Forest just peeks from behind the elegantly researched narrative to lend a knowing detail. This is a risky wire act. Don’t fall into self-aggrandizement (his genuine modesty saves him that) or the net of hagiography. And best to name this from the start, in the subtitle: “biography” and “memoir,” a difficult art Forest has mastered.

We Die Before We Live

For Dan Berrigan, to 'proclaim the resurrection in word and act is an affront the State cannot tolerate.'

On April 30, 2016, Catholic peacemaker and activist Daniel Berrigan entered life eternal. He was a teacher and friend to many in the Sojourners community. Read more reflections on Dan's life and legacy in the August 2016 issue.

I ONCE HAD a conversation with Dan about his death. We were talking late into the night at the Block Island hermitage that his friends William Stringfellow and Anthony Towne had built for him while he was two years in Danbury federal prison, a consequence of the 1968 Catonsville draft board action. He had by then foresworn scotch, on doctor’s orders, so I was being introduced to Manhattans dry, which were somehow allowed. The place suited the topic. On the wall above us was an exorcism poem that he’d hand-lettered in a style familiar to Catholic Worker and resistance houses across the country.

I’m certain it was I who broached the topic. When we met in the early ’70s, it was in the wake of notorious assassinations: Medgar Evers and Viola Liuzzo, the Panthers, Malcolm, King, the Kennedys. There was a certain youthful grandiosity in imagining that he or others who were such troublesome peacemakers would be similarly targeted. I braced my heart. I told him so. (Then he turns around and lives, thanks be, to 94!)

Struggling to Become Human

In scholarship and life, Walter Wink sought the truth with passion.

WALTER WINK IS known as a lectionary commentator with lucid biblical insight, a chronicler of nonviolent practice, a scholarly essayist, an arrestee in direct action, and one of the most important theologians of the millennium’s turn. He effectively named “the domination system” and its collusive principalities, opened up biblical interpretation to an integrated worldview, and brought the New Testament language of power back on the map of Christian social ethics.

Two years ago he crossed over to God, joining the ancestors and saints. His first two posthumous books have now appeared. They make for good companion volumes. Let me weave back and forth between the two. Walter Wink: Collected Readings is the anthology of his core work. Just Jesus: My Struggle to Become Human is a short autobiography. The second is the more remarkable—because it’s so rare that a world-class scripture scholar should tell his or her own story in relation to encounters with the biblical witness. And all the more so because it was a project undertaken after he was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia.

Given the dementia, the book itself is an effort of his “struggle to become human.” An early version of the manuscript included oral history and other sources narratively adapted to a first-person voice, but in the end his partner in all things, June Keener Wink, pressed for it to be pure Walter. No words not his own. His voice is easily recognized in these pages, though not always in the familiar crafted and noted style, rich in quotable one-liners. The jewels are here all right, but this text feels simpler, sparer, plainer. There are prayers and memories of one suffering the weight and creep of memory loss. Though it is a book he conceived and set to writing, June (aided by a sainted editor) lovingly completed the sculpture with autobiographical pieces, journal entries, prayers, dreams, and important portions of his final magisterial work, The Human Being: Jesus and the Enigma of the Son of the Man. The latter, also well represented in Collected Readings, frames the struggle (Jesus’, Walter’s, and our own) to become human.

From the Archives: April 1985

Authority Over Death

IN THE EARLY weeks of the Eastertide lectionary, there appears a series of texts from the third and fourth chapters of Acts ... Peter and John, on their way to temple prayers, heal a man begging at the beautiful gate. His joy begets a sermon from Peter on the resurrection, at the close of which the disciples are arrested and spend the night in jail. The next day in court they again testify boldly, refuse to comply with the court's order, and are released after calculated threats from the authorities. Their release prompts prayers of thanksgiving in the community.

An Assault on Local Democracy

Michigan's "Emergency Manager" law and Detroit's future

A big change came down in Detroit this spring. Under sanction of Michigan’s Emergency Manager Law (Public Act 4), on April 4 the city council authorized a “consent agreement” ceding its authority over the budget to a shadow body of corporate leaders (emergency manager by committee). For some, this bodes fast-track redevelopment and downsizing the city. For others, it means the end of collective bargaining. For Detroiters, it’s the blunt face of political disenfranchisement.

Although Public Act 4 is being challenged for its constitutionality in court and for its political legitimacy in a statewide repeal effort, the assault on local democracy remains in full tilt. Triggered by financial insolvency, governor-appointed emergency managers are empowered from above to remove top administrators and elected officials, void union contracts, cut and remake budgets, overturn local ordinances, and sell off assets. The “consent agreement” keeps the mayor and city council in place, but vastly disempowered.

But, apart from the vacant land so plenteous these days in the city, are there assets in Detroit to be desired and seized? The water works may quickly be sold or controlled by a suburban arrangement. It is one of the few revenue-generating departments in the city, and it is among the key infrastructures of white urban sprawl. Then there is the riverfront itself, and the gem-of-an-island city park, Belle Isle, which casino-owners and developers have eyed lasciviously for years. There are newly built or rehabbed schools sought by for-profit charters. There is the privatization of services or entire city departments. And, of course, the deregulated clearing of the way for projects yet to come.

Walter Wink: Remembrance and Reflection

Walter Wink, 76, a world-class biblical scholar and non-violent practitioner, crossed over to God on May 10 at his home in Western Massachusetts. Following a slow decline, he had been in hospice for several weeks in the company of his beloved June and their family. (See "Confronting the Powers," Sojourners December 2010)

As a first year seminarian in New York City, more than 35 years ago, I was fortunate to have Walter as my New Testament instructor. In a seminar session on the "pearl of great price" in Matthew, I have a vivid memory of him breaking the discussion so we could go round the circle and each reply to the question: "For what would you be willing to die?" I don't so much recall my own halting answer, as the depth of the question he understood was put to us by the text. It's since become my conviction that no one should escape seminary (or baptismal preparation for that matter) without facing with that query.

Which is to say he was himself an engaged scholar, connecting the academy with the risk of the streets. While filling his first teaching post at Union Seminary in New York he was simultaneously serving on the national steering committee of Clergy and Laity Concerned about the War in Vietnam (1967-76).

He was notorious for foundation-shaking works. When I met him, Walter was a rising star in the biblical guild, on the fast track at Union. Then he published a little polemical book called The Bible in Human Transformation (1973) which made bold to declare, “Historical biblical criticism is bankrupt." It assailed the myth of scientific objectivity, the disembodied approach which kept the text at arms length and pre-empted commitment. In many respects it anticipated the contextualizing hermeneutics of feminist and liberation readings, but it didn't win him friends in the academic guild.

Harry and the Principalities

The 10-year pop culture love affair with Harry Potter leaves questions at the crux.

The Passion of the Gulf

The BP catastrophe invites us to take a hard look at ourselves. We invited eight writers to offer their reflections on images from the Gulf Coast disaster.

Resurrection City

Auto idolatry and casino economics have left Detroit tottering on the brink. What will it take for Motown to rise again?

Ambassadors

Ambassadors. I'm a sometimes preacher, these days a Methodist holding forth among an Episcopal congregation in Detroit.

An Ethic of Resurrection

The timeless and timely vision of William Stringfellow