THE DAY AFTER the presidential inauguration in January, Episcopal Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde, preaching at a prayer service for unity attended by President Donald J. Trump, warned members of the new administration that contempt is “a dangerous way to lead a country.” She pleaded for their mercy and compassion for the most vulnerable and outlined a vision for social healing founded on genuine “care for one another.” Budde’s words stand in stark contrast to the campaign of dehumanization and destruction we’ve witnessed since.

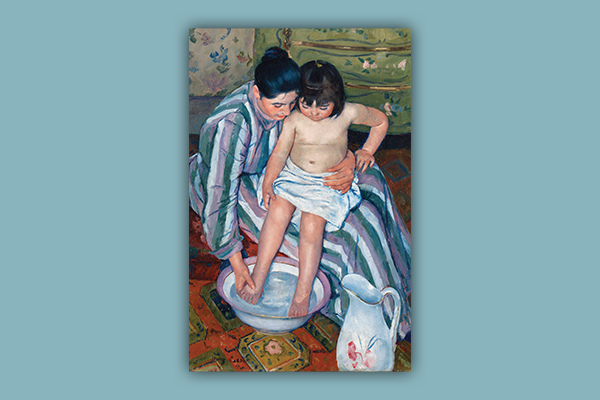

In the last few months, I’ve contemplated how, with incredible grace, Budde spoke truth to the power sitting before her in the pews. Her sermon left me feeling calm and convicted and brought to mind one of my favorite artists, the 19th-century impressionist Mary Cassatt. Like Budde’s sermon, Cassatt’s paintings are striking in their softness; they remind me of the kind of activist and person I want to be. I want to live with my heart softened and meet suffering with tenderness.

As Ruth E. Iskin explains in Mary Cassatt Between Paris and New York, Cassatt was “neither simply or completely a bourgeois, nor fully a precursor to the 1890s New Woman, but a mixture of both.” She was “anchored in a transatlantic network that included numerous conservative Americans” and an independent working woman who passionately supported women’s suffrage and full emancipation. In a male-dominated art scene, Cassatt made a name for herself with humanizing portraits of women of all ages, showing the relationship between caregivers and children and the dignity of motherhood. Her layered, emotionally vulnerable pieces highlighted the strength of women and the beauty and seriousness of care itself.

Her politics were characterized by a similar sensitivity. Iskin explains, “[Suffragists] claimed that the very role of mothers in the private sphere justified extending their activity into the public sphere of politics and government.” In other words, they made the case that the qualities of love, strength, and commitment exhibited by many women in their homes would also benefit civic spaces.

Read the Full Article