IN 2015, I visited two plantations in rural Louisiana to write a college paper on white supremacy. One, Whitney Plantation, centered the experiences of enslaved people by sharing “firsthand accounts” and including statues of and memorials to them. The other, Oak Alley Plantation, romanticized the Antebellum South. Filled with indignation, I could not fathom how tourists at Oak Alley drank mint juleps where brutality, violence, and terror once reigned. Clint Smith, author of How the Word Is Passed, studies sites of racialized violence in the U.S. to help form a more accurate American “public memory.” We need Smith’s poetic-sociological vision to help us tell the true, humanizing stories of our — often ugly — history.

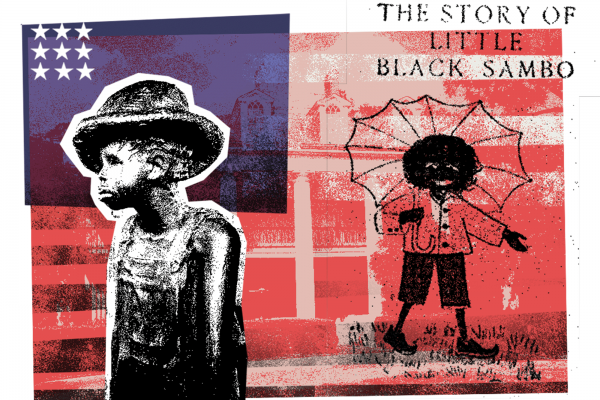

During my visit, Oak Alley sold copies of Little Black Sambo by Scottish author-illustrator Helen Bannerman in its gift shop (the shop no longer sells this title). A racist children’s book about a family that is widely understood to be Tamil, the 1899 children’s book portrays dark-skinned Indian people through heavy “pickaninny” caricature. In the book Racial Innocence historian Robin Bernstein explains, “The pickaninny was an imagined, subhuman black juvenile who was typically depicted outdoors, merrily accepting (or even inviting) violence.” The dangerous trope desensitizes us to violence against Black and brown children, evidenced throughout history from slavery to police brutality. My family is part Tamil, and I nearly choked when I saw this “artifact” of dehumanization dressed up as nostalgia.

Read the Full Article