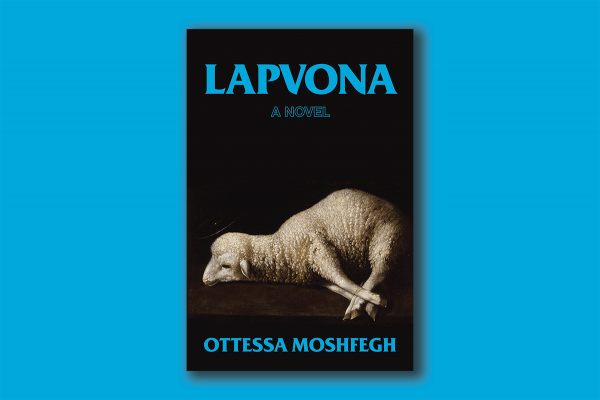

WHAT IS A devout village to believe in during a time of famine and plague? Ottessa Moshfegh presents a story devoid of hope and redemption in her latest novel Lapvona, proving that in dire times, believing is not a want but a need.

Moshfegh has a flare for brutality (Eileen and Death in Her Hands). With Lapvona, Moshfegh has crafted a medieval fantasy in the vein of Game of Thrones. It reads like a fairy-tale epic for adults, with its cast of fringe characters and fable-esque sequence of events. But this fantasy is far more depraved: As religious as the villagers are, there is no redemption to be found in this village.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login