Aug 8, 2022

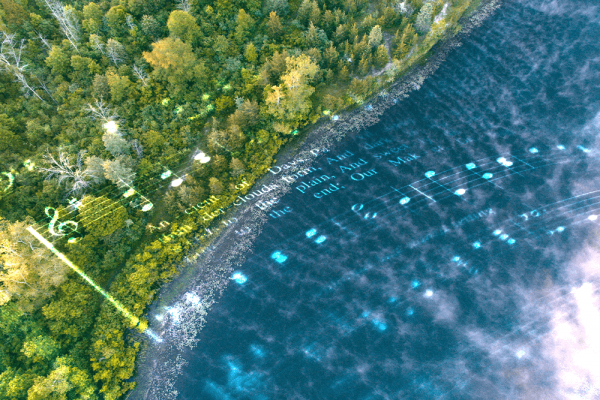

The June release of a Climate Vigil The Porter’s Gate Worship Project aims to nudge Christians toward climate action, but it isn’t alone among contenders to inspire the climate movement. For over 20 years, Carolyn Winfrey Gillette, a Presbyterian minister from New York, has written hymns for the times, including one for the 2021 UN climate talks held in Scotland and several to recognize increasing natural disasters such as wildfires, hurricanes, and floods. Fossil Free PCUSA, a campaign within the Presbyterian Church (USA) has used hymns in protests, including songs by Christian artist Matthew Black.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login