ALL THE SUNDAY School classes were gathered at a plaza in Buenos Aires. After months of preparation, we were there for the churchwide tournament. Participation was mandatory; the competition was public. Glory or shame for all to see. Our task was to recite by memory an arbitrary list created by the teachers — the Lord’s Prayer, Psalm 23, names of all twelve apostles, the books of the New Testament and, for extra credit, the Old Testament ... in order. A church elder stood ready to score children in each category.

My arrogant 9-year-old self stepped up first. Everyone knew I was going to be a pastor. My parents had helped me. My sister and I had practiced. I had to know this stuff. The elder at the “Lord’s Prayer station” nodded for me to begin.

“Padre nuestro que estas ... .” He began to shake his head. “En los cielos, santificado sea tu nombre ... .” He made a noise with his tongue; his face looked like he had sucked a lemon. “No” he commanded, waving his hands. “In Taiwanese!”

Tears burned down my cheeks. I should have known. It wasn’t so much our faith on trial that day, but the degree of our “Taiwanese-ness.” My Taiwanese Presbyterian Church was raising not just Christians, but Taiwanese nationalists. The language of the church had to be their version of “pure” Taiwanese. I knew it could never be Mandarin Chinese but Spanish was unacceptable too. As my moment of glory turned to shame, I ran into the park to cry alone.

The Power of Culture

MY PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH introduced me to Taiwan’s version of Christian nationalism.

I was born in Taiwan 27 years after the Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) party seized the island of Taiwan after losing the mainland to the Chinese Communist Party. Between 1947 and 1987, the KMT established a one-party, authoritarian state that ruled with terror and violence. More than 140,000 Taiwanese citizens were incarcerated and tortured. Thousands more were assassinated — including my grandfather, who was a pastor and seminary professor. In 1981, my family fled Taiwan (a country under martial law) to Argentina (a country entangled in the “Dirty War”).

The Taiwanese Presbyterian Church was always a hub for Taiwanese resistance against Chinese invasion. Forged under oppression, the exiled church I grew up in became the vehicle by which to raise nationalists who would fight for Taiwanese independence and resist the evils of mainland China — even from far-away Argentina. Thus, their version of Christian nationalism was born. Taiwanese superiority was implicit in all church activities and explicit in some. In the diaspora this nationalism was even more extreme. It went far beyond respecting our past or holding on to the language of our parents. This was about imposing a vision of God’s justice that included a sovereign Taiwan independent from Chinese influence.

As I grew up and moved outside Taiwanese circles, I was exposed to other forms of Christianity that pushed me to question what I had been taught as a child. My family moved to the United States. Eventually I became a Presbyterian pastor. I even took a call at a Taiwanese Presbyterian Church to push back against the nationalism that lingered. I thought I could change them. I failed and left to pursue a doctorate in sociology to better understand the power of culture.

My experience with Taiwanese Christian nationalism helped me recognize the white Christian nationalism I saw in the U.S. because both operate under the same logic. White Christian nationalism is a religious fabrication that forces adherence to an imagined identity. Its doctrines and practices are concerned with passing on the moral code that glorifies and normalizes the myth of the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant, middle-class, nuclear family. It serves as a religious vehicle for preserving fictitious cultures. It preaches good news for those already at the center of power, rather than to the marginalized who need it. Christian nationalism is an effective theodicy for self-made white victims: Where is God when bad things happen to white people? God is restoring a Christian nation in which whiteness will once again reign supreme.

Whether among the white evangelicals I worked with in Virginia or the Taiwanese Presbyterianism in which I was raised, Christian nationalism has one goal: Use God to bless human ambition for power. This is not new. From the “city upon a hill” to Manifest Destiny and beyond, Christian nationalism has always been part of American Christianity.

tony_two_1.png

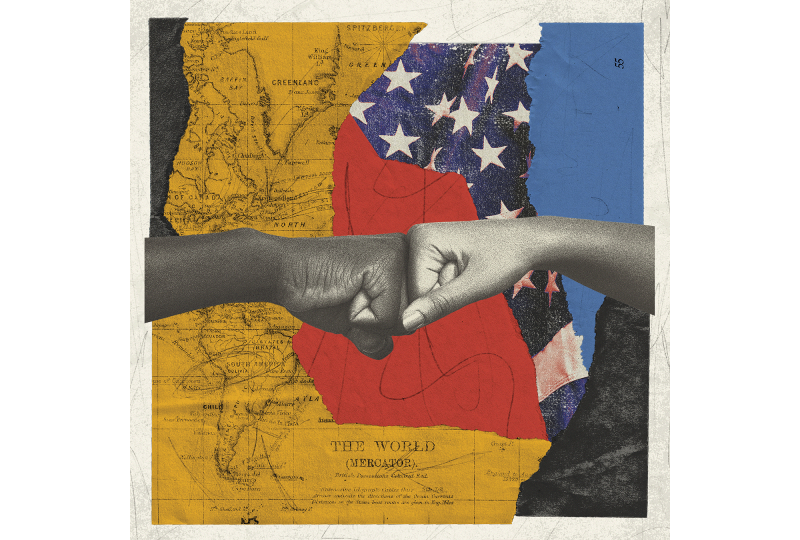

Are We ‘All Americans’ Now?

RECENTLY, MEDIA HAS reported a rise in ethnic minorities who appear to support white Christian nationalism. If white supremacy is key to Christian nationalism in the United States, then why are some ethnic minorities aligning with it? Or are they?

In 2005, I began an in-depth national study of Latino Pentecostal congregations, focusing especially on the role of the prosperity gospel in Latino communities. In all my years researching, worshiping in, and even pastoring Latino congregations, I have not found Christian nationalism per se to be prevalent in these churches.

Yet data shows that Latino evangelicals voted for President Trump and opposed his impeachments more than Latinos of other religious orientations. A positive correlation between Trump support and church attendance was also found. Both patterns seem to indicate a religious push toward the right.

“Latinos” as a group, however, are extremely diverse. In fact, this nation’s multiracial dream has always been our reality. Latinos are of every race and trace their roots through multiple continents. We present in the full spectrum of skin complexions. Even Asian Latinos (like me) are a growing demographic.

Seventy-two percent of all Latinos in the U.S. are fluent in English, with nearly a quarter identified as “No Sabos” (Latinos who can’t speak Spanish). All our countries have a version of empanadas, and they all taste different. Every few years our countries of origin play against each other in Copa America, the soccer championship of the Americas, rekindling our pride in our ancestral lands, even as we are all Americans now.

We are multilingual, multiethnic, and multicultural in a nation that historically punishes difference and forces groups into social hierarchies. Yet our sheer number forced the U. S. Census to acknowledge that individuals can fit more than one classification. So, the census bureau created a new classification for us: “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.” This is our gift to America. This gift is also our antidote to ethno-nationalism.

Scholars have shown that white Christian nationalism is fueled by white racial victimhood. It unites around an ideal of whiteness and all the privilege it represents. What looks like a rise in Christian nationalism among some Latino, Black, and Asian Christians does not develop as it does among white evangelicals. Social scientists show that although Christian nationalism views both religious diversity and racial diversity as a threat, when it comes down to it, it’s the racial dynamic that holds. The link between Christian nationalism and political violence is sharply conditioned by white identity, a perception of victimhood, and support for conspiracy theories.

I would argue that average Latino congregations are not following the path of white evangelical megachurches in political activism. Church attendance has long been associated with greater political activism, including voting. While Latinos have higher rates of church attendance than whites, they vote at a much lower rate. In fact, Latinos have the lowest voter registration and turnout of any ethnic group in the 2020 election. Nearly half of all Latinos who were registered to vote did not turn up at the polls. In 2022, only 58 percent of Latinos were registered to vote.

By the 2024 U.S. presidential election, Latinos could potentially be the largest nonwhite voting demographic, accounting for nearly 15 percent of all eligible voters. But historically, they won’t vote as a bloc and only half will cast a ballot.

Christianity in Decline

WHY THE LACK of political participation?

While some Latino churches have better attendance than the average church in America, nearly all Latino Protestant churches are facing financial decline and an aging population. Like all churches in the United States, including white evangelicals, Latino church attendance overall is dropping. Rapid population growth among Latinos has not translated into church growth. The share of Latinos who are Protestants has dropped to 21 percent from its peak of 26 percent just six years ago. Catholics now make up only 43 percent of all Latinos, down from 67 percent in 2010.

Population growth due to immigration has bolstered some Latino congregations. But, since the 2000s, Latinos born in the U.S. — not immigrants — are the main driver of Latino population growth. Nearly half of Latinos born in the U.S. since 1994 identify as “religiously unaffiliated.” Conversely, only about 20 percent of Latinos ages 50 and older describe themselves as religiously unaffiliated (and 56 percent of these were born outside the U.S.).

Additionally, Latino churches have always played a significant role in supporting recent immigrants. But with declining numbers, aging congregations, and dwindling finances, when recent younger immigrants arrive, they may find limited support and little reason to stay. This may further the cycle of decline.

More consequentially, the percentage of Latinos in the U.S. who agree that religion is “very important in their lives” has dropped significantly. Between 2007 and 2023, the number of Latino Protestants who agree with that statement dropped from 65 percent to 56 percent. Among Latino Catholics during the same period, agreement dropped from 68 percent to 46 percent. Even Latino evangelicals’ agreement dropped from 85 percent to 73 percent. This pattern is reflected in Christians of all races in America. Against this backdrop, many Latino faith leaders are juggling multiple jobs while struggling to sustain their congregations. They are busy attending to the immediate needs of their members and those in the local community. In general, they have little time to invest in the long game of political influence.

tony_three_1.png

‘Miraculous Meritocracy’

THEOLOGICALLY, LATINO PENTECOSTALS in particular rarely engage in political activism because they believe in what I call “miraculous meritocracy.”

The majority of Latino Pentecostals are committed to the idea of meritocracy (a prevailing doctrine in American Christianity far beyond Latinos). They believe that their hard work and determination will pay off. It is one of the reasons they and their parents immigrated. They believe in being the captain of their own souls. This is the central myth of the American Dream — if you work hard and follow the rules of the dominant (white) culture, you can succeed economically and socially.

Yet these communities are not naïve to the very real obstacles they face. Thus, they have miraculous meritocracy. They work hard, live moral lives, and stay relentlessly optimistic not because they will earn their reward but because God will perform a miracle that will grant them their wishes.

Under the doctrine of miraculous meritocracy, hard work and sacrifice are critical. Like other Christians, they believe that God can heal them and help them financially. What is unique about this meritocracy model in some Latino churches is the explicit entitlement to those tangible economic and social rewards — you deserve this, and God wants you to have it. Any doubts or fears are signs of unfaithfulness that will sabotage one’s blessing. It is a guaranteed transaction provided that the believers hold up their end of the bargain. Those faithful who work the hardest and make the greatest investments and sacrifices will be rewarded with a miracle — in the form of a payoff from God.

Miraculous meritocracy must be taught, especially to immigrants to the United States. It goes against the communitarian ethos that most arrive with and serves to assimilate them into the individualism of American consumer culture. With this worldview, working for a national social safety net or expecting government “handouts” may be interpreted as a sign of unfaithfulness. One should not look to the government or other institutions to do the work one must faithfully do to earn God’s blessings. God will deliver to the deserving.

What Lives Within Us

CHRISTIAN NATIONALISM IS not a new concept in the United States. It is intertwined with America’s greatest challenge: white supremacy, which has ruled our nation since its inception.

White supremacy is hegemonic, which means even those who are oppressed uphold the oppressive system as righteous. It’s not just a temptation for white evangelicals or Anglo-Saxon Protestants, its allure reaches into all our communities. That is why so many immigrants are wholeheartedly committed to the various ideologies that hold up white supremacy, such as neoliberalism, meritocracy, moralism, and even the American Dream. In all its manifestations, these ideas sustain white supremacy to empower some and dehumanize all, even the oppressors. But the same white supremacy that forced many of us out of our homelands also created this nation we now call home. We are all victims and beneficiaries of white supremacy. Many of us carry white supremacy in our DNA. That is a messy truth to reckon with.

As Christians, can we try to recognize the evil within us even as it crushes us? If we can learn to acknowledge, accept, and disarm it, then possibly we can give birth to what author Junot Díaz calls “blasphemous solidarities” — the willingness to confront what we perceive as abhorrent in ourselves and others in order to elevate our shared and inherent human dignity.

“Our trying,” writes Díaz, “ ... must be complex and fearsome and, yes, impossibly compromised. To reckon with a past like slavery we must be willing ... to entertain blasphemous solidarities with the very thing that sought to destroy us and seeks to destroy us still.” The promise of our gospel is that we will not be destroyed.

So let blasphemous solidarity be our divine call. Let the liberating power of the gospel of Jesus give us the courage to live out the diversity and contradictions we carry in our lives so that we may be empowered to transform principalities and powers that rule this world and dare to imagine a new way of living together. We, who gave this nation new categories of being, we can do this.

In that park in Buenos Aires, when I responded in the wrong language, I was shamed into hiding but also called into hope. Alone and crying, a group of children and adults came looking for me. “Lo podemos hacer en Castellano! We can compete in Spanish!” they shouted. It turned out most kids had memorized the responses in the only language they knew: Spanish. The church elders gave in.

Others might have set the rules, but together we can change them.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!