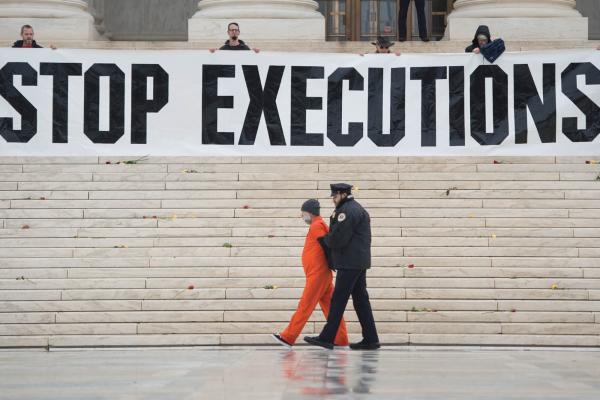

ON MARCH 13, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed an order issuing a moratorium on the state’s death penalty—providing a reprieve from execution for 737 people on death row. Newsom cited as reasons that the ultimate penalty provides no public safety benefit and has no value as a deterrent. As someone who has worked as a public defender inside the criminal justice system for 30 years, I applaud the humanity and compassion of his decision.

While the number of countries that employ the death penalty dwindles, the United States and several others still enforce it. Despite strong empirical evidence to the contrary, we are led to believe capital punishment is reserved for the “worst of the worst” and that it is supported by victims and law enforcement alike. Leaving aside that 156 people on death row nationwide have been exonerated since 1973, the death penalty is discriminatory in its application and in the selection of those whom the state seeks to kill. It is largely sought because of the economic status of the defendant, the race of the victim and the defendant, and where the crime took place, not because of the circumstances of the offense.

Read the Full Article