IN HIS 2013 book The Great Divergence: America’s Growing Inequality and What We Can Do About It, Timothy Noah notes that the personal income of the top 1 percent in the United States began to increase exponentially beginning in 1979, a peak year in what economists call the “Great Inflation” (1965-1982). While there has always been economic stratification in the U.S., the “great divergence” in American’s incomes began at the end of the 1970s, and the wealth gap has continued to grow. In 2019, people in the top 1 percent of income distribution held more than 33 percent of the total U.S. wealth — up from 27 percent in 1989, according to a Congressional Budget Office report. Families in the bottom half held only 2 percent of the total wealth. The U.S. has policies that protect wealth and others that depress wages and hinder affordable housing. This combination increases poverty. Unfortunately, false narratives still circulate about the causes of poverty, blaming the poor and pitting communities against each other.

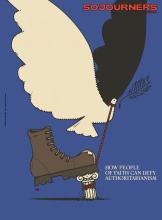

From another point of view, acceptance of wealth disparity, and the policies that cause it, is a result of failed imagination: We accept increasing wealth disparity because we cannot envision another way. As people of faith, we are called to be God’s prophets and seers — to see the possibilities of God where others cannot. The church’s task is to challenge empire’s narratives about what is possible, to actively cultivate what biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann calls a “prophetic imagination” for a different reality and empower communities to embrace it.

Read the Full Article