IN THE GREEK mythology I was taught as a child, a recurring plot always struck me as deeply unfair. A god seduces—or rapes—a mortal woman, who either succumbs to the coercion or tries to resist. If she resists, she is punished. If she gives in, a jealous goddess punishes her.

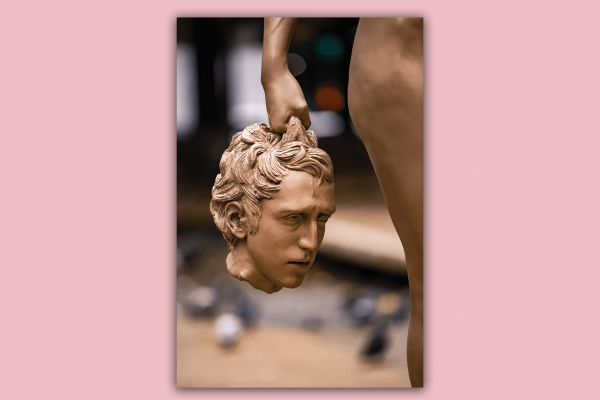

The fact that my classmates and I had to read these myths without being encouraged to deconstruct them still disturbs me. My desire is not to sanitize art nor neuter its political incorrectness, but rather to see people (especially children) realize their agency as readers, particularly in instances where misogyny should be questioned. Which is why the installation of Luciano Garbati’s sculpture Medusa With the Head of Perseus in New York City represents a delightful inversion.

As the story goes, Medusa was a beautiful young woman, unfairly punished for being a victim of Poseidon’s lust. Because the rape takes place in Athena’s temple, Athena, believing her sanctuary defiled, turns Medusa into a monster. Medusa, now with snakes for hair, is so hideous that she can transform anyone who beholds her to stone. Perseus, a demigod himself, is tasked with killing Medusa, a duty he executes via beheading. A 16th-century bronze by Benvenuto Cellini, titled Perseus With the Head of Medusa, depicts Perseus in his moment of triumph. He holds Medusa’s head aloft while snakes emerge from her neck.

Read the Full Article