Reviews

IT FEELS GOOD to laugh out loud. In the past year I haven’t felt lighthearted about weighty topics such as our political leadership, globalization, and climate change. But Bill McKibben’s latest book, Radio Free Vermont, reminds me that humor can be as powerful as protest in speaking truth to both injustice and abuse of power. Prolific writer, climate organizer, Sojourners columnist, and co-founder of the organization 350.org, McKibben has given his life to galvanizing the climate movement. He advocates for a diversity of strategies, from a carbon tax to public art, with a seriousness reflecting the high stakes of inaction. In his first work of fiction, the satirical plot of Radio Free Vermont revolves around the exploits of Vern Barclay, a 72-year-old radio announcer who finds himself at the center of a campaign to convince Vermonters to secede from the U.S. His motley crew of allies includes Perry Alterson, a teenager with technological expertise who ends every sentence with a question; Trance Harper, a former Olympic biathlon winner; and Sylvia Granger, a firefighter who harbors these fugitives while teaching investment bankers and corporate attorneys how to drive in the mud and fell trees for firewood in their new state. The narrative begins with acts of nonviolent and almost joy-filled resistance by the accidental activists, which include taking over the airwaves at Starbucks with Radio Free Vermont (“underground, underpowered, and underfoot”) and the rather polite hijacking of a Coors Light truck to replace the cargo with Vermont craft beers (which are mentioned by name in nearly every chapter). It’s like the Vermont Welcome Wagon received training in civil disobedience, with a local brew never far from reach.

EVEN AFTER 200 years, Henry David Thoreau continues to be a controversial (and, to some, annoying) figure. In a 2015 New Yorker article titled “Pond Scum,” Kathryn Schulz eviscerates the 19th century author of Walden, describing him as “self-obsessed: narcissistic, fanatical about self control.”

Schulz is not alone in her criticism. In Thoreau’s own beloved village of Concord, Mass., he was attacked for being a hypocrite because he would slip away from his hand-built cabin in the woods to enjoy hot meals and drop off his laundry at the family home. This after he had brazenly declared himself self-sufficient. To make matters worse, he thundered against alcohol, gluttony, and sex in Walden, just as many were happily putting Puritanism behind them.

Yet Thoreau not only endures but is thriving in today’s 21st century zeitgeist. He has “come down to us in ice, chilled into a misanthrope prickly with spines,” declares Laura Dassow Walls, author of a recently released biography, Henry David Thoreau: A Life.

Walls writes of Thoreau set in a New England deep in the throes of change. Ever mindful of the worrisome new global economy, Thoreau sought out and wrote about those being left out and struggling. His subjects included Native Americans, Irish immigrants, and ex-slaves, who were living precarious lives along Walden Pond. Perhaps his interest stemmed from the fact that, for years, Thoreau’s own extended family lived a life of penury, according to Walls, before the small pencil factory they ran in their backyard prospered, making them comfortable during Thoreau’s adult years.

IMAGINE A gathering of thoughtful American Christians, of diverse backgrounds—from Greek Orthodox to Pentecostal—and each with some experience of the conflict between the Israelis and Palestinians. If you could record their conversations, it might be the beginning of the book that is here before us.

A Land Full of God is an essay collection compiled by Mae Elise Cannon, executive director of Churches for Middle East Peace, to show a range of opinions about the Israel-Palestine conflict in the American church. The writers share a general understanding that peacemaking is the only way forward. Some admit they are exhausted by this conflict. Many express despair over the extremist voices that seem to push the U.S. church around. And a few have suggestions for what might make a difference.

In one of the book’s liveliest essays, Paul Alexander sums up key points: 1) Israel must end its military occupation of the Palestinians and be less violent. 2) Palestinians need to recognize the state of Israel and stop vilifying Jews. 3) Christians need to give a rest to appeals to eschatology in this entire mess. Alexander sounds exasperated and pragmatic, feelings many of us share.

If you’ve had much contact with this topic, it is impossible to read such a book with any neutrality.

THROUGH MOST OF my career at World Relief, welcoming refugees has been a fairly easy “sell” to local churches: Refugees have sympathetic stories of fleeing persecution and legal status. I spent most of my energy persuading Christians that the same scripture passages that compel us to welcome refugees also apply to undocumented immigrants.

In recent years, I have observed a shift. The questions after I speak to church groups increasingly focus on Muslims. Aren’t I concerned that Muslims will “take over” America? What percentage of refugees harbor terrorist sympathies? Was I aware, one man asked, that New York City was already under sharia law? (Fact check: It’s not.)

We may have reached the point where refugees are as controversial as undocumented immigrants. Certainly, many local churches do welcome refugees—and this relational proximity has disabused many Christians of misconceptions that all refugees are Muslim (among those resettled to the U.S., more are Christians) or that Muslims immigrants want to establish sharia as U.S. law. But evangelical churches that actively welcome refugees are in the minority. A Public Religion Research Institute poll finds that 74 percent of white evangelicals believe “the values of Islam are at odds with American values”—essentially, that Muslims cannot possibly become Americans. Six in 10 white mainline Protestants and white Catholics agree.

TA-NEHISI COATES is an atheist, but in We Were Eight Years in Power he atones for sin. In a 2008 article about Bill Cosby for The Atlantic, Coates failed to thoroughly report on the sexual assault allegations brought against the comedian, only mentioning them briefly. On page 12 of We Were Eight Years in Power, Coates repents. “That was my shame,” he writes. “That was my failure. And that was how this story began.”

By “this story,” Coates means his ongoing career as a correspondent for The Atlantic, during which he has received a MacArthur genius grant, a National Magazine Award, and several other honors for his writings on race in America. Coates is one of the nation’s most popular living chroniclers of the plight of African Americans. But despite that, he is acutely aware of his failings.

We Were Eight Years in Power is both a collection of Coates’ best articles published by The Atlantic and criticism of those pieces. Prefacing most of the articles are short essays by Coates about the stage of life he was in when he wrote each article, the pieces’ triumphs, and their flaws. With sometimes savage specificity, the essays map the evolution of Coates’ writing skills as well as his personal foibles. At the same time, the articles themselves document the flaws of the United States and how the country consistently does wrong by its African-American citizens in favor of doing more than right by its white citizens.

Coates’ writing process is a metaphor for the social corrective he pursues: the abolishment of white supremacy.

It’s been a year of unease. Neo-Nazis, hurricanes, and threatening tweets sent by orange-tinged fingers have left me wondering, “What’s next?”

Wendigo , the latest album from indie folk duo Penny and Sparrow (Andy Baxter and Kyle Jahnke), didn’t answer that question for me. Rather, their somber melodies provided something I didn’t realize I needed—space to confront the uncertainty.

According to Chippewa poet Louise Erdrich, the wendigo “is a flesh-eating, wintry demon with a man buried deep inside of it.” Some Indigenous communities see environmental destruction, exclusion, and greed as indicators of “wendigo psychosis.”

Many wendigos seemed to appear after the 2016 election. Not just in the White House, but also in families, friends, and neighbors. The song “Kin” calls to mind Thanksgiving dinner with pecan pie and family members-turned-strangers. “Where the hell did your spine go? / Did you cut it out? / Did it never grow?” the lyrics ask.

THIS IS A BOOK I wish I could have had when I was 15.

While there are numerous (and much needed) stories about the immigrant experience, Mitali Perkins’ young adult novel, You Bring the Distant Near, fully captures nuances of relationships, racism, death, family, feminism, sexism, and love in profound ways. It’s a story that’s not often told with such clarity and depth.

Reading this book was like staring into a mirror and seeing my reflection—sometimes surprised, sometimes in tears, and other times nodding in understanding.

It weaves together the lives of five women from three generations—Ranee, Tara, Sonia, Anna, and Chantal (nicknamed Shanti)—and focuses on Tara and Sonia’s journey from when they were teenagers to when they were mothers with successful careers.

Ranee is a strong-willed, stay-at-home, Indian (Bengali) immigrant mother who comes to the U.S. with her husband for opportunity. She is the mother of Tara and Sonia. Tara is charming, peacemaking, and theatrical in the best ways. She is a shape-shifter of sorts, able to fold into any culture by studying and learning what traits she needs to be the most ideal version of that culture (when she arrives in the U.S. she emulates Marcia Brady). Sonia is fiercely intelligent, outspoken, and a brilliant writer. Anna is Tara’s creative, brazen daughter who is proud of her Indian roots. Shanti is Sonia’s athletic and easygoing daughter who loves math and dance.

Each woman represents a different side of femininity that together shows the reader the importance of multiple, empowering narratives.

THE SACRED ENNEAGRAM infuses a centuries-old personality typing system with an often-neglected perspective: grace and compassion. With nuance and genuine curiosity, Christopher L. Heuertz moves beyond personality caricatures common to many writings on the Enneagram and explores the complexities of being fully human. Rather than type-calibrated condemnation, Heuertz’ insights extend affirmation, hopefulness, and an invitation to self-liberation.

A sacred map to the soul, as described by Heuertz, the Enneagram illumines a journey of discovering our true self beyond false identities upheld by “self-perpetuating lies.” This transformation begins with an honest awakening to how we have invested in one of nine identity illusions and continues as we begin to relinquish our defense of this surface-level version of ourselves. Through self-observance and “empathetic detachment,” we cultivate the gifts of mental clarity and emotional objectivity and increase our capacity to reflect the essential nature instilled within us. In this slow conversion toward embracing the imago dei within, we return to God.

Interwoven throughout this work is the wisdom of master spiritual teachers. Thomas Keating’s “three programs for happiness”—in which happiness requires an integrated balance of security and survival, affection and esteem, and power and control—is brought alongside Henri Nouwen’s “three lies of identity”: I am what I have, I am what other people say or think about me, and I am what I do.

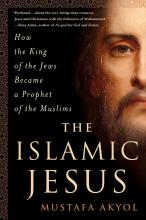

AFTER A CHRISTIAN missionary handed Mustafa Akyol a Bible on a busy Istanbul street, the Turkish journalist became fascinated with the many similarities between his Muslim faith, Christianity, and Judaism. As a moderate Muslim, Akyol had been studying the Quran with a group of friends for some time. He used his study group discussions as background to inquire about the other two religions.

The result is The Islamic Jesus, which takes the reader on a complex, winding journey, detailing many of the profound historical and religious bonds of the three religions. They “are like three siblings,” explains Fred M. Donner, a respected historian of Islam, in a University of Chicago lecture. He points out that there was quite a bit of fluidity and interchange among these “siblings” in the first few centuries after the Prophet Muhammad died in 632.

Akyol, who writes for the Turkish newspaper Hürriyet Daily News and The New York Times International Edition, became engrossed early on with the different ways that Jesus is portrayed in the New Testament and the Quran. The New Testament, of course, describes Jesus as divine, part of the Trinity, and the son of God. The Quran is reverential toward Jesus, and he is seen as the last Jewish prophet, but not as divine. The Islamic view is that there is only one God, and no Trinity.

SOUTH ASIAN-AMERICANS, such as Siddhartha Mukherjee and Atul Gawande, have recently made a dent in the white male hegemony that has reigned in medical writing for general audiences. Haider Warraich is following in their path with this new book on death and dying.

With liberal use of anecdotes from a medical residency in Boston, Warraich snaps the reader out of sanitized TV portrayals or even hospital experiences of death to induce a more authentic confrontation, one most would seemingly rather avoid at all costs. (Witness church members who no longer have funerals but “celebrations of life” and “homegoings,” often after enduring dehumanizing and futile end-of-life interventions.)

But is lack of knowledge about the mechanics of “modern death” in a technological society at the core of the problem, as Warraich seems to think? Is his thesis correct that our fear of death is greater than ever? Can social media posts by the dying overcome these problems?

WHILE OPENING a star-studded concert for victims of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, musician Stevie Wonder remarked: “Anyone who believes that there’s no such thing as global warming must be blind.”

These two major hurricanes had just ravaged Texas, Florida, and much of the Caribbean. While scientists are cautious about ascribing causation to any individual storm, they do not hesitate to say that warming waters and altered weather patterns due to climate change will cause many more such destructive events in the future.

As we watched the horrific scenes on our television screens, one thing was clear—the most vulnerable suffer the most.

REV. OSAGYEFO Uhuru Sekou’s album In Times Like These does something I’ve never witnessed any other recorded musical project do: It sings before track one even begins. Printed on the inside of the album’s CD case is one of the most powerful commentaries on the 2016 U.S. presidential election I’ve read. “The Task of the Artist in the Time of Monsters,” written by Rev. Sekou, is simultaneously an artist statement, a poem, and a call to action for the world to engage passionately in “the art of loving and living.”

Sekou’s album is a rousing sermon that may re-energize social justice activists who listen to it, keeping them engaged in “the movement.” At the same time, it’s also an extended prayer of sorts, lamenting the wrongs of the world and asking God to alleviate society’s pains. “In times like these / we need a miracle,” Sekou sings in the chorus of the album’s title track, one of the project’s standouts.

However, despite his call for divine intervention, Sekou doesn’t allow believers in a higher power to sit back and rest assured that God will do the work they should be doing. He completes the chorus of the song “In Times Like These” with the much-appreciated but potentially controversial statement: “Ain’t nobody gonna save us / We the ones we’ve been waiting for.” In a time that calls for bold, social justice-minded commentary from artists, Sekou delivers.

NOEL PAUL STOOKEY has been a musical voice for peace, love, and justice for more than 50 years. With his new solo CD/DVD set, At Home: The Maine Tour, he builds on the legacy of Peter, Paul and Mary as well as on his considerable solo work. The 24 songs on this album were recorded in a 2014 tour of nine towns in Maine, where he and his family have lived for some 40 years. They incorporate not just folk, but also rock, pop, and jazz. Although they span his career, they are not a nostalgic gaze at the past but a testament to Stookey’s ongoing creativity and social ethic.

The performances are intimate and relaxed while possessing a vital energy that courses through the whole sequence. They warm the heart, evoke laughter, comment on social concerns, call for justice, touch pain, and promote Love with a capital “L.” Through his stage presence, humor, and invitations to sing along, Stookey connects easily with a live audience. In the DVD, close-up shots of his hands and face give the viewer a feeling of a one-on-one encounter. Adding to the intimacy is the fact that the songs are from one voice and one acoustic guitar. Stookey’s skillful playing exhibits the right combination of gentleness and boldness.

I FIRST BEGAN watching The Leftovers, HBO’s drama based on a novel of the same name by Tom Perotta, when it debuted in the summer of 2014. Like many viewers, I was fascinated by the premise: On Oct. 14, 2011, 2 percent of the population suddenly disappears in a rapture-like event. The show begins three years after what is called the “Sudden Departure,” and rather than explaining the metaphysical meaning of this mysterious event, it focuses on how the members of one family process their grief.

Throughout the show’s first season, we’re introduced to an array of characters who deal with the Sudden Departure in different ways. Some want to continue with life as it was on Oct. 13, 2011, before the world changed. Some are tortured by the mystery of the Departure and why they weren’t “taken.” Some seemingly well-adjusted people join the cults that have sprung up since the event. One group in particular has gained the most traction, the Guilty Remnant. The group exists to be “living reminders” of God’s judgment; they make it their mission to make people remember, but offer no comfort. Another cult features a messianic leader who promises to absorb the pain of anyone who hugs him, but offers no spiritual or intellectual balm for the hurt and confusion post-Departure.

The novel on which the show is based was written as a response to the way the world changed after Sept. 11, so it was particularly poignant that the attacks in Paris occurred as I watched the second season of The Leftovers. Certainly it’s grievous to see violence occur anywhere, but as with Sept. 11, the attack on Paris brought with it a shocking cognitive dissonance: That kind of thing doesn’t happen in places like this—Western, cosmopolitan, relatively safe. Before the attack in Paris, before the Twin Towers fell, there was always the possibility that something tragic could occur on a random Friday night or Tuesday morning. But perhaps to many of us who live in relative comfort and ease, violence and tragedy are what happens to other people, in other places. It is this cognitive dissonance and the subsequent question of how to live in uncertain times that the second season of The Leftovers explores. It is also what makes it worth watching.

I HAD GEARED myself up for a sort of Job-God exchange between Mary Oliver and some wild roses in the aptly named “Roses,” from her latest collection of poems, Felicity.

This is the scene: The narrator, full of poetic angst and existential fatalism, approaches some huddled roses and wonders in their direction: “What happens when the curtain goes / down and nothing stops it, not kissing, / not going to the mall, not the Super Bowl.”

I was ready for the roses to respond in a whirlwind full of rhetorical questions about the wonder and origin of creation. Instead they deflect the inquiry: “‘But as you can see, we are / just now entirely busy being roses.’”

And I laughed. In the past, Oliver’s poetry has caused me to cry over a dog (see “The First Time Percy Came Back”) and pray accidentally (see “The Summer Day”), but never before had her poems made me laugh.

In her 2014 collection Blue Horses, the flowers are “fragile blue.” They are “wrinkled and fading in the grass” until the next morning when somehow they crawl back up to the shrubs, bloom a bit, decide they want—just like all of us—“a little more of / life.” Now, in her latest collection of poetry, Oliver’s flowers are red, and they want as much life as they can get. They are carefree roses with a love of causal banter and a kind distaste for troubling existential questions.

AT FIRST GLANCE, Abigail Disney’s documentary The Armor of Light seems straightforward: It’s about guns and escalation of mass shootings in the U.S. But at its core, the film looks at the complicated relationship between evangelical Christianity and this country’s gun culture. It is just as much about theology as it is about politics.

The film follows the story of Rob Schenck, a conservative evangelical minister whose strong pro-life views about abortion are at the center of his work and advocacy on Capitol Hill. But with each instance of gun violence he hears about, Schenck becomes convinced that calling himself pro-life rings hollow without a critical look at our gun culture. He can no longer ignore the association of guns with evangelical Christianity.

Schenck’s story intersects with that of Lucia McBath, the mother of Jordan Davis. In 2012, Davis, a black teenager, was shot and killed at a Florida gas station in a dispute over the volume of his music. The man who fired the shots, a 45-year-old white male, tried to justify his actions by the “stand your ground” law, explaining he felt threatened by the presence of Davis and his three friends. In response to the death of her child and the following legal battle, McBath became involved in gun-control advocacy.

Coming to the issue from different paths, McBath and Schenck find themselves both allies and foils. McBath, the mother whose son was murdered for being black and present, identifies as pro-choice, while Schenck gained national attention for protesting women’s health clinics in the early 1990s in Buffalo, N.Y.

This already has the makings of a compelling story, but the film hits its stride not in character development but in the theological questions it poses. In addition to discussing the effects of gun violence on those who are killed, Schenck questions what this pervasive gun culture does to those who defend it.

He pushes against the platitude “the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun,” asking who can definitively categorize others in such black-and-white terms. Likewise, the film asks why so many Christians seem to place more trust in a piece of metal than in God. McBath tells Schenck, “We have replaced God with our guns as the protector.”

AN OLD Buddy Guy song is titled “First Time I Met the Blues.” I don’t remember the first time I met the blues, but I do remember that I was captivated by the music. For many years now, two of my passions have been listening to blues and studying the Bible. Gary W. Burnett, a lecturer in New Testament at Queen’s University in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and an amateur blues guitarist, shares those passions. This book, he writes in the introduction, is his attempt “to combine in some ways these two passions and to be able to reflect on Christian theology through the lens of the blues.” He succeeds with a well-crafted synthesis of U.S. history, African-American history, the blues, and New Testament scholarship.

Blues music is one of the great contributions of African-American culture to the U.S. While rooted in the oppression of slavery and post-slavery Jim Crow, it speaks meaningfully to the experience of all people. It’s a music that grabs your soul and won’t let go. And Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount is central to his message of life in the coming and present kingdom of God. It can also grab your soul and not let go. By juxtaposing blues lyrics with passages from the Sermon, Burnett shows the common themes that emerge.

MANHOOD SEEMS to be in crisis today, for a host of reasons ranging from silly (a feminized church because of too many altar girls?) to serious (a porn and video game epidemic, alienating boys and men). Carolyn Custis James’ Malestrom gives needed context by pointing this crisis of masculinity back to humanity’s very fall into sin and the patriarchy that sin generated. She calls this patriarchy the “malestrom”—a societal whirlpool that sucks men into a broken way of life and destroys them.

The malestrom is unfortunately familiar to us, although James explores its contours in compelling detail. Sin manifests itself in men through a patriarchal hierarchy that leads us to resort to violence to establish status. The dominant model of what it means to be a man is to father children, provide for them economically, and protect them from the outside world. In light of this, how can we be surprised that we have hurting men and boys in our church who don’t fit in that model?

James tells biblical stories of men who pushed back against the patriarchal order to better reflect the image of God—men and women together in a “blessed alliance” to bring God’s kingdom. These stories culminate in the example of Jesus as the ultimate man who lived fully into a healthy masculine identity.

VATICAN II attempted to change the Roman Catholic Church from an insular and defensive purveyor of 19th century religious practices to one with an incarnational theology and a vigorous recognition that the laity are called to be holy and to participate actively in the Church. Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen tried to live this out in his Seattle archdiocese, making changes that empowered both men and women and trying to build a diocese that was indeed “the people of God.”

A record of this important work and its devastating fallout are at the heart of A Still and Quiet Conscience. Hunthausen’s early years growing up in a close and very Catholic family, attending an old-school seminary, serving at Carroll College and as bishop of Helena, Mont., and now living in prayerful retirement, are interesting bookends. However it is a fearsome Vatican investigation into Hunthausen and its ambiguous result that are the center of this well-researched and helpfully indexed book.

I was angered when I read of the duplicity, divisions, and cover-ups within the Catholic Church in the last years of the 20th century. The “irregularities” cited as the reason for the investigation into Hunthausen were practices also found in other (uninvestigated) U.S. dioceses, such as letting people discuss the ordination of women, allowing unleavened bread at Communion, and allowing the gay rights group Dignity to worship on church grounds.

USERS OF MAPS—that’s all of us—may suppose that what we see is factual, accurate, bias-free. Of course location, distance, elevation, and comparative importance are reliably shown!

Not so fast, says social activist and pastor Ward L. Kaiser. A map may be “right” in some ways but still dangerous to the way we live in the world.

Why? Because maps are layered with meaning. Surprisingly, their most important messages may lie beneath the surface. In his full-color book How Maps Change Things, Kaiser helps the reader to dig in and discover some of those hidden, mind-bending messages.

As a college chaplain I am acutely, sometimes painfully, aware of the often-hidden narratives and symbols that define us as individuals and as a culture. This book has helped me analyze how maps—an increasingly pervasive form of symbolic messaging and storytelling in our time—connect us to power and privilege or consign us to society’s also-rans.