On Film

When Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev met in what has been seen as the beginning of the end of the Cold War, the venue was an unassuming house overlooking the sea in Reykjavík, Iceland. Höfði House had been previously occupied by the poet Einar Benediktsson, who once wrote, “Take notice of the past if you would achieve originality.” Whatever else Einar meant, at this house, the necessity of learning from history can’t be ignored.

It is easier to imagine today’s enemies talking once you’ve seen the house. You see, it’s not the Avengers’ home base or one of those underground lairs favored by James Bond villains. It’s just a house, surrounded by the typical trappings of a small city—business headquarters, cafes, supermarkets. The Icelandic government uses it today for social gatherings. And what happened in it 30 years ago was at heart two people communicating, with a shared goal that transcended them both.

The notion of enemies sitting down and talking with each other is also at the heart of the magnificent new Icelandic film Rams, which I saw in a cinema about five minutes’ walk from Höfði. Two sheep-farming brothers live and work beside each other, but haven’t spoken for four decades. A family shadow has driven them apart—one of those decisions made by parents seeking the best for their children but not knowing how to arrive there. And so, separately, the brothers endure twice the hardships and experience only half the blessings of life amid this most exquisite landscape. Success is ignored by the other, or serves as an occasion for jealousy rather than celebration; Christmas is spent alone, no one to share the feast, and Icelandic winters are hardest of all.

THE MOVIES AND MEANING community recently published our list of greatest films, based on the idea that in a great film the highest aims of craft and the most humane visions meet. It seeks a “third way” between one reactionary notion, that art should be judged on the basis of what it portrays rather than how it portrays it, and another—that content is morally neutral. I say bring it all: love and pain and action and laughter and grief and sex and violence and horror and contemplation. To extend Roger Ebert’s notion, a movie is not only about what it’s about, but it’s also about how it’s about it.

The most beloved films on our list include The Tree of Life (in which the most enormous, transcendent existential questions mingle with the most ordinary of tragedies and blessings), Lone Star (which aims for nothing less than the healing of U.S. memory, for survivors and perpetrators alike), and Wings of Desire, Beasts of the Southern Wild, and Spirited Away (which use magic and the supernatural to remind us of the miracle of everyday life). The top 10 also includes Schindler’s List—a testament to monstrous suffering and extraordinary courage alike—and the Three Colors trilogy, which does the seemingly impossible: take a national political virtue and fully embody it in the life of an individual.

The new version of The Jungle Book is too recent for the list and hasn’t had the chance to prove its staying power, but what a glorious surprise it turned out to be. The beloved 1967 cartoon is held in great affection, but affection that requires turning a blind eye to its colonialist and racist undertones—particularly the literal aping of some black cultural tropes by a character presented as nonhuman, whose greatest desire is to “be like you.” The 2016 version works to transcend white supremacy and even critiques human interference with the rest of nature. When a villain comes to a violent end, it’s not through the hero’s superior strength but through the bad guy’s own selfishness.

STANLEY KUBRICK’S Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb was released in 1964, and it was echoed later that year by a film on a similar topic, Fail-Safe. Directed by Sidney Lumet, Fail-Safe imagined the idea of a nuclear explosion being unpreventable by the people supposed to be in charge of it. Strangelove is hilarious but chilling satire; Fail-Safe is just chilling. The central notion, that ethics can’t be trusted to machines, lingers today: George Clooney produced a live television version of Fail-Safe as recently as 2000.

A current version of the dilemma is brilliantly portrayed in Eye in the Sky. Cutting between four main locations (a British government committee room, a military control center in the English countryside, a Nevada drone piloting bunker, and the Kenyan house from where a suicide bomb attack may be launched), it’s like a relentless tennis match in which the crisscrossing ball is a matter of life and death.

Who decides who can be killed? If blowing up the house will prevent an attack that might kill 80 people, how much does it matter that a little girl selling bread nearby will probably die too? What is legal? Does “legal” mean “right”? Such questions have rarely been handled with such compelling dexterity in a movie. Eye in the Sky deserves comparison with Dr. Strangelove and Fail-Safe because it doesn’t offer easy answers, only difficult questions, and its seamless movement between locations fully immerses the audience inside the debate. But it transcends those earlier films because of the way it treats the characters that might be seen as “other.”

EXTRAORDINARY British actor Mark Rylance has a noble theatrical reputation but has only recently found prominence in movies, most notably in the wonderful Steven Spielberg Cold War film Bridge of Spies, for which he recently won the best supporting actor Oscar. Speaking of Spielberg, Rylance made a beautiful point: “Unlike some of the leaders we’re being presented with these days, he leads with such love that he’s surrounded by masters in every craft.” This gentle wisdom—that good leaders attract good teams—echoes the message of Bridge of Spies, which illuminates the possibility of talking to each other across boundaries of militancy, misunderstanding, and fear. It is an invitation to loving leadership, criticizing a mutually destructive strategy by practicing something better.

Amid the noise of “some of the leaders we’re being presented with these days,” I’ve been indulging in a little comfort-watching, asking Charlie Chaplin to help me discern a way through. Chaplin’s brave, hilarious, and deeply moving film The Great Dictator does to authoritarianism what C.S. Lewis says the devil cannot tolerate: It mocks evil, revealing its pretensions. Chaplin’s courage has rarely been matched. Today his mantle may be held by Sacha Baron Cohen, whose trilogy of pride-puncturing, diversity-affirming films, Borat, Brüno, and especially The Dictator, is brave enough to challenge prejudice when it’s not safe to do so. These three are in the same tradition as Dr. Strangelove, In the Loop, Four Lions, Dave, and the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, which make us laugh at the absurdity of political control, taking away some of its power.

If comic portrayals of bad leadership are comforting, serious cinematic explorations of bad leadership might help us learn how to avoid it. Nixon, Downfall, the Godfather trilogy, Citizen Kane, The Apostle, Beasts of No Nation, The Act of Killing, Leviathan, and There Will Be Blood all present warnings of what happens when leaders are self-interested, unaccountable to an emotionally mature community, and not mentored in tending to their inner lives.

WATCHING THE much-awarded film The Revenant is an ordeal, but its director Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s films have such energy and compassion that I hoped the payoff would be worth the stretch. Iñárritu’s early films Amores Perros and 21 Grams rehumanize characters who make bad choices, with an attention to scale that might be described as Napoleonic.

The Revenant is the loosely historical tale of Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio), an early 19th century fur trapper left by his companions for dead after a bear attack, agonizing his way to track his betrayer (Tom Hardy) through some of the most frozen wilderness in cinema. The commitment of DiCaprio and Hardy has been rightly applauded—this is a cold and exhausting way to make a film. And the craft is monumental—arrows seem to land on the audience, the bear attack is terrifying, the camera hardly ever stops moving. But the exploration of the futility of revenge at the heart of this story is confused.

AS THE Academy Awards approach, I’d like to mention some films worthy of recognition by the lights of a different set of criteria. As a member of the Arts and Faith Ecumenical Jury, I am delighted to present our list of films from 2015 that “challenge, expand, or explore” faith, including those that illuminate religion and spirituality, pointing to a more humane vision of the world.

The choices are much more diverse than the usual annual polls. Multifaith stories (Irish Catholic, Israeli Jew, Iranian Muslim, just to start), exposés of injustice and calls for restoration, exile, and return, the damage done by immature religion, and the possibility of human spiritual evolution—all are here. And the film we agree was the year’s best does something profoundly important: It tells the story of a weaponized individual who spends her time doing everything she can to avoid killing.

Some in our top 10 I’ve written about here before—our number nine is the fun and wise animated map of the emotions, Inside Out; eight is the immigrant tale Brooklyn; five is Brian Wilson mental illness and creativity biopic Love & Mercy; and four is the powerful investigative journalism drama Spotlight, a challenge to contemporary news media to once again pursue their higher calling to tell the truth for the common good. Here are the rest of our selections:

10. About Elly. Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi made this film in 2009, and it has been acclaimed as heralding “a new genre,” but it was not released in the U.S. until last year. Farhadi’s magnificent, compassionate dramas A Separation and The Past are more recent, but his ability to tell the most humane stories in the most gripping way was forged here.

HERE ARE my picks for the best films of 2015. Honorable mentions for Creed’s operatic dignity and subtle advocacy of racial reconciliation; The Forbidden Room’s unabashed creative inspiration; Mad Max: Fury Road for being a pro-feminist action film; Spectre for James Bond going beyond an eye for an eye; Grandma, Lily Tomlin’s crowning achievement as an actor embodying that it’s okay to be different; and Room, part-thriller, part-existential exploration, honest about trauma and the lengths love will go to protect the vulnerable.

10. Shaun the Sheep. A delightfully inclusive, breathtakingly crafted story about humans, animals, and nature as one family. With frenetic comedy and an open heart, it honors the marginalized, critiques superficiality, and even lets the villain live to learn his lesson.

9. Me and Earl and the Dying Girl. An indie comedy-drama that avoids cliché and makes heroes out of nerds.

8. Beasts of No Nation. Evoking Apocalypse Now, a harrowing story of child soldiers, the legacy of colonialism, and how violence is transmitted from one generation to the next.

7. Clouds of Sils Maria. A stark reflection on identity and the conversation each of us has with the voice(s) in our head. Olivier Assayas’ film asks if we are living from the inside out or for external reward.

6. Brooklyn. A poetic and compassionate painting of the paradox of finding home as an immigrant.

MICHAEL FASSBENDER'S uncanny performance as Apple Inc. co-founder and CEO Steve Jobs begs the question of how someone so clueless about human relationships could win the hearts of so many people. Of course, the performance and the Aaron Sorkin script it’s based on are not the same thing as the man himself. Steve Jobs may be unfairly treated by Steve Jobs. The question of its accuracy is not unimportant, and people who knew him deserve a hearing. But the film only sketches a persona rather than providing an encyclopedia of the soul.

Treating Steve Jobs as a film about power and personality evokes the Quaker teacher Parker Palmer’s notion of an “undivided” life. Palmer quotes Rumi’s warning, “If you are here unfaithfully with us, you’re causing terrible damage.” One facet of this unfaithfulness is the difference between living “from the inside out” and living primarily for external reward. Undivided lives are punctuated by initiatory experience, familiar to our ancestors, and now re-emerging in communities such as the ManKind Project and Woman Within. Initiatory experiences take people into the depth of their psyches, supported by wise elders, opening a crack that lets in the light of transformation. Initiated egos thrive in balanced service to the highest self and the common good (so the wise elders tell me).

The Steve Jobs in Steve Jobs has no such initiation—he seems basically the same shallow egotist at the end of the movie as he was at the start. The joy of Steve Jobs is the kinetic dance of image and sound, and actors at the top of their game (Kate Winslet as the definition of long-suffering colleague, Seth Rogen in a rare dramatic role, and Michael Stuhlbarg, all of them representing prickly conscience). The problem of Steve Jobs is that it omits engagement with the personal transformation that many think unfolded for him as his products achieved something like omnipresence. There’s no initiation here, unlike in Bridge of Spies, where Tom Hanks risks his life to negotiate a prisoner swap in a gripping, if light, Cold War thriller. Mark Rylance’s accused Soviet spy emerges more humanized than Jobs’ community-building entrepreneur.

When I first saw the DeLorean rush toward me at the end of Back to the Future, I was 11 years old, and I felt alive in a way that I’m not sure I had experienced before. The endings of the films of Robert Zemeckis would continue to give me that rush of good feeling—Tom Hanks at the crossroads in Cast Away, and on the tree stump waiting for his little son to come home from school in Forrest Gump; Denzel Washington faced with the question “Who are you?” in Flight. Some critics, believing that things need to be difficult in order for them to be good, find it easy to turn down a Zemeckis invitation. I beg to differ—there’s no contradiction in loving the populist sentiment of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, the serious melodrama of The Elephant Man, the painful and nonlinear narrative of Exotica, the surreal plunge into the human shadow of Enter the Void, and the high art intellectual sensibilities of Eternity and a Day. And those are just a handful of very different films beginning with the letter “E.” Authenticity is what matters, not how “elite” the work can appear to be.

Zemeckis makes large-scale populist entertainment that makes us laugh and cry, but he deals in authenticity. Along with the fun and the flights (Forrest running across the U.S., Marty McFly and Doc Brown’s race to connect the wires with the clock tower, and two of the most harrowing plane crashes in the movies), emotional beats are earned, characters behave as they might in real life (even if they are in a time-traveling sports car or abandoned on an island), and audiences get the chance to wrestle with the same question faced by Denzel: Who am I?

MY FRIEND the architect Colin Wishart says that the purpose of his craft is to help people live better. Just imagine if every public building, city park, urban transportation hub, and home were constructed with the flourishing of humanity—in community or solitude—in mind. We might be inspired to create new, hopeful thoughts, friendships with strangers, or projects that bring transformation into the lives of others.

It is easy to spot architecture divorced from its highest purpose. In a building or other space made to function purely within the bounds of current economic mythology—especially those created to house the so-called “making” of money—the color of hope only rarely reveals itself. Instead we are touched by melancholy, weighed down by drudgery, compelled by the urge to get away. But when we see a space whose stewards seem to have known that human kindness, poetry, and breathing are more important than the “free” market, we realize that it is possible to be always, everywhere, coming home. Think of a concert hall designed for the purest acoustics, a playground where the toys blend in with the trees, a train station where the transition from one place and way of being to another has been honored as a spiritual act.

THE TEACHER Edwin Friedman believed that good leadership creates conditions for people to find tools to become emotionally mature. In other words, no matter what its stated goal (civil rights, community organizing, religious engagement), the most important purpose of leadership is to help us become more fully human.

Of course this is also true for artistic endeavors—stories that create emotional dependency in audience members are not offering good leadership, and they usually make for bad art too. We may like them, as they satisfy the surface-level desire for easily grasped narratives and quick resolution. But that’s the aesthetic equivalent of a cheap burger. Our deeper hunger is for stories that strive to tell the truth about life and its possibilities, that demand self-reflection, and that permit subtexts to breathe so we can fill in the gaps.

I saw three such films recently. Inside Out displays astonishing imagination, bringing us into the human psyche to figure out how we think. There’s genius in a story that gives the five core emotions personalities, wisdom in how it makes honest work of how people confront change, and a delightful bonus in the form of Bing Bong, a character with all the lovableness of Baloo the Bear and a purpose with which Carl Jung would be pleased. Inside Out offers no shortcuts to spiritual well-being. It’s film-as-therapy that’s as entertaining for kids as it is wise for adults (and vice versa).

AVENGERS: AGE OF ULTRON asks what happens when you give a computer the ability to think for itself. To which we could add, what happens when you make a science fiction film that assumes the audience can think for itself?

Sadly, in the case of Age of Ultron, writer-director Joss Whedon’s serious attempt to make a smart blockbuster collides with corporate cookie-cutting and the belief that stockings are best overstuffed, even if what’s in them is just cotton wool or dead weight. Too much is going on, and not all of it is good. Thor, the Hulk, Iron Man, Black Widow, and the other guy with the arrows are still looking for a magical object, but when they find it we’re none the wiser about what it’s for. Bad guys still threaten the safety of the world, and the Avengers still think that only maximum force can secure a result.

IT’S THE 50TH anniversary of The Sound of Music. I never thought I’d write about it here, but someone recently offered me the kind of gentle admonishment that Maria might have given to the von Trapp children. Maria is usually right, and my friend is too. One of the wisest film critics I know, a man dedicated to contemplation and activism and who doesn’t shy away from the more challenging edges of cinema, still considers it his favorite film.

THE EXTRAORDINARY film Leviathan takes place in a tiny coastal town on the other side of the world, but it relates to all our dreams and fears.

A man is tormented by bureaucracy, as the authorities try to take his house. He has an unhealthy relationship with alcohol, and a very unhealthy one with his partner. He works on people’s cars, does favors for people who ask him, and tries to raise his son as best he can. And he’s caught between the wheels of historic oppression and emerging forms.

Leviathan, this year’s Russian nominee for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, is a work of uncommon cinematic bravery, for the people who made it take on the corruption of their current political masters. Vladimir Putin appears briefly, as a portrait looming over the office of the mayor trying to take our hero’s house. But the graft, selfishness, and cruelty of Putin’s imperial reign are palpably present in the mayor, who has been fighting the householder for years to get his property, for reasons that owe more than a little to the legacy of Soviet-era patriotic ideology. Communism has been replaced by a heady mix of nationalistic pride and elitism religion, whose boundaries are enforced with no mercy. Pussy Riot’s punk prayer gets a mention in a priest’s litany of things that are undermining Mother Russia. It’s the same old story, there and everywhere—keep the nation pure, confuse spirit and law, and wreck your own life by denying the glories of human diversity.

CLINT EASTWOOD has made films about the sorrow and repeating pointlessness of war, as seen through the eyes of both aggressor and aggressed-against, with empathic performances and unbearably moving impact. His American Sniper, about the most lethal sniper in U.S. military history, bloodied in Iraq and struggling at home, is not one of those films. At best it’s a valuable character study of a confused warrior, revealing the traumatic effect of his service. At worst it’s a jingoistic and xenophobic attempt to put varnish on a terrible national response to the horror of 9/11, a response that became a self-inflicted wound creating untold collateral damage.

A decade ago, Eastwood made Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima, which saw World War II soldiers as propaganda fodder and had the moral imagination to show both sides as courageous and broken without denying the difference between attacker and defender. These films are respectful and thoughtful, but American Sniper is arguably a work born in vengeance. Its reception (becoming one of the biggest January box office weekends ever, and a quick right-wing favorite) is part of the failure to deal in an integrated way with the wounds of 9/11, or to even begin to face the reality of the war in Iraq: an imperial conquest using the cover of national trauma as a justification

FOR TWO YEARS in a row we have seen significant films about oppression and struggle nurture public consciousness. Selma and 12 Years a Slave invite us to reimagine iconic moments closer than we usually think, their protagonists more like us. Slavery had not been portrayed in such visceral fashion in a mainstream film before 12 Years. Before Selma, images of Martin Luther King Jr. had never quite transcended the almost superhuman projections that accrue from his martyrdom and decades of being co-opted by cultural mavens from Apple to Glenn Beck.

These films create new benchmarks for the mainstream depiction of black history, black struggle, and wider perceptions. But entertaining portrayals of inspiration contain a powerfully dangerous substance that needs to be handled with care. The cathartic tears shed at a film about other people’s suffering and heroism can also be a narcotic, implying that the work has been done. Think of all the talk about freedom struggles after Braveheart, or challenging the principalities and powers after The Matrix. The problem was, most of it was just that. Talk.

THIS PAST MOVIE year I’ve been delighted by, among other things, nonviolent resolutions, a guy talking in a car, an Irish priest trying to do the right thing, and a five-dimensional bookcase. Here’s my list of the 10 best films of 2014 (many more are worthy, but 10 are all that will fit).

10. Pride. A delightful and stirring celebration of marginalized people turning their woundedness into helping others, as LGBTQ activists support the Thatcher-era British coal miners’ strike.

9. The Lego Movie. This turned out to be both the most unpredictably fun and one of the wisest films of the year. A brilliant critique of consumerism and political tyranny, with an ending that inverts the myth of redemptive violence.

TOOTSIE, the 1982 Dustin Hoffman comedy in which a failing actor cross-dresses to win a part on a soap opera, is a lovely, problematic film (and just released in an excellent home edition from www.criterion.com). It’s controversial in some quarters for playing the idea of a man dressing as a woman for laughs: The joke is on any male-bodied person who challenges macho stereotypes. As when The Da Vinci Code attracted criticism for portraying a character with albinism as an insane assassin, like almost every other comparable movie has treated albinism, Tootsie represents a time when the extent of mainstream cinema’s engagement with what it thought constituted “trans” was to portray cross-dressing for laughs. But a cisgender straight character dressing up has little or nothing to do with the real stories of the “T” in LGBTQ.

Cinematic LGBTQ characters seem to evolve one step forward and a half back—beginning with their invisibility, then moving through psychopathy (the “evil queer” of Hitchcock’s Rope still shows up in The Lion King and The Avengers); martyrdom (Kiss of the Spiderwoman, Philadelphia, Brokeback Mountain); safe best friends (The Prince of Tides and My Best Friend’s Wedding); and eventually redemption (Milk, the wonderful recent Pride). The evolution continues: George Carlin’s gay best friend caricature in The Prince of Tides was in good faith, but would not pass muster today. We’re shaking off the idea that LGBTQ characters can only be suffering or sassy.

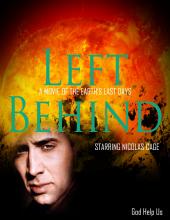

LEFT BEHIND may be a soft target, but once seen, you may realize that it’s a soft target for anyone who has ever been on an airplane, seen what Nicolas Cage is capable of in Leaving Las Vegas, met a Muslim, or not been cryogenically frozen since the era when it was socially acceptable to treat people with dwarfism as punchlines.

It really is worse than most theatrically released movies—shot and edited like a political attack ad/music video mashup, written like a child’s Sunday school lesson, and then strangely denuded of almost anything that would make it identifiably Christian (teasing those who already believe, yet scared of alienating people who just want to see a cheesy disaster movie without heavy proselytization).

The people who made it aren’t bad people, of course. (I’m not sure anyone is, with the line between good and evil running through each human heart and all—although that’s another argument that wouldn’t make it into this film.) The producers are ideologically committed to advancing a message that they were indoctrinated into by an unthinking system—let’s call it the Christian Industrial Entertainment Complex. They’ve stumbled upon the money and basic skill to make movies. They think that what they’re doing is changing the world for the better, but that’s doubtful—it’s more likely just reinforcing the closed-set worldview of the CIEC’s pre-committed adherents. This isn’t new, so I’m not too concerned about one more example of bad art masquerading as religious experience.