WHEN I TOLD my oldest son I was writing about universal basic income (UBI), he said, “All I know is that the Silicon Valley guys are pushing it, so it must be bad.” And he had a point. UBI has entered U.S. political debate most prominently as Silicon Valley’s favorite solution to a problem mostly of its own creation—massive permanent job loss due to artificial intelligence and robotics.

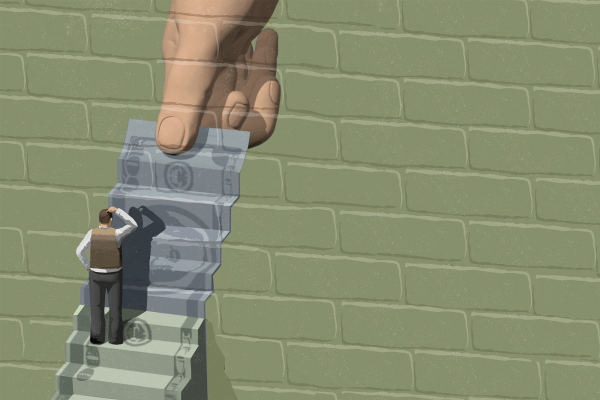

Under a universal basic income policy, all U.S. citizens would receive from the government a regular, permanent payment of, say, $1,000 per month, regardless of their other income or employment status. It wouldn’t get rid of the grotesque income inequality in the U.S. In fact, it wouldn’t even guarantee each person a decent standard of living. But it would get everyone up to the official poverty level.

Tech industry UBI proponents include Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, Tesla founder Elon Musk, and Amazon kingpin Jeff Bezos. But the idea is most identified with former Silicon Valley entrepreneur Andrew Yang, who made it the defining issue of his long-shot campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Still, UBI is an idea much older and bigger than any of its shadier supporters. While the term “universal basic income” is of fairly recent coinage, the idea that every human deserves some share of the earth’s bounty is an old one. In 1797, one of America’s founding philosophes, Thomas Paine, wrote that “the earth, in its natural uncultivated state was, and ever would have continued to be, the common property of the human race.” But, Paine continued, “the system of landed property ... has absorbed the property of all those whom it dispossessed, without providing, as ought to have been done, an indemnification for that loss.”

Paine proposed a single payment at the attainment of adulthood as compensation for the loss of our natural right to the earth. Paine was echoing the ideas of some of the earliest Christian teachers, including St. Ambrose (340-397 C.E.), who wrote: “God has ordered all things ... so that there should be food in common to all, and that the earth should be the common possession of all. Nature, therefore, has produced a common right for all, but greed has made it a right for a few.”

So universal basic income is not just the latest Silicon Valley fad. It’s rooted in an understanding of the origins of wealth and of our obligations to each other that is consistent with both our democratic and religious traditions.

But that still leaves plenty of room for debate about whether UBI is the right solution for America’s most pressing social and economic woes.

How Would UBI Work?

ECONOMIC DEBATE OVER the past 50 years has offered a variety of UBI-type proposals, from Richard Nixon’s negative income tax to the social wealth dividend proposed by some contemporary democratic socialists. The best-known and most-debated current UBI plan is the one proposed by the Yang campaign. This version of UBI rests on three pillars:

First, it is “universal.” Everyone gets it, without conditions—from Warren Buffett down to the apparently able-bodied guy with the “Please Help” sign at the exit ramp. That, of course, raises the first blizzard of objections. Why give money to rich people who don’t need it or purportedly irresponsible people who might waste it?

Paying for UBI would almost certainly involve new taxes on the wealthy, so Warren Buffett wouldn’t be keeping his $1,000 per month. As to the fear of aiding the “undeserving poor,” it’s true that historically most of the meager social benefits offered in the U.S. are means-tested (for those with the very lowest incomes) and conditional upon some form of good behavior (hours worked, clean drug tests, etc.). This has helped create a culture that stigmatizes public benefits as “welfare” and brands beneficiaries as, if not sinful, at least defective.

Read the Full Article