This article is excerpted with permission from You Mean It or You Don't: James Baldwin's Radical Challenge, 2022 Broadleaf Books.

IN 1958, Greek American film and theater director Elia Kazan asked James Baldwin to write a play. Specifically, Kazan recommended that he write a script based on the 1955 murder of Emmett Till in Money, Miss. The result was “Blues for Mister Charlie,” a play that proved to be one of the most intimate, gut-wrenching, and emotionally exhausting experiences of Baldwin’s artistic life.

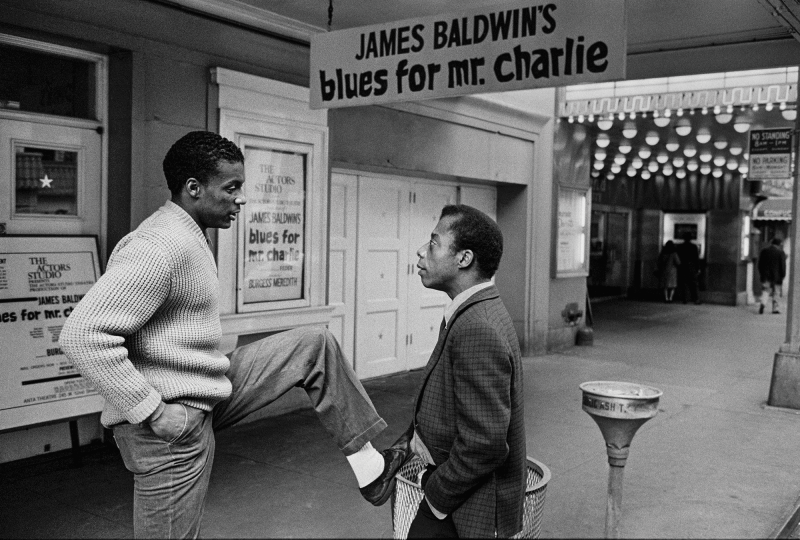

As Baldwin worked on the script during the summer of 1963, he received the crushing news that his friend Medgar Evers had been killed. Evers was a civil rights activist and U.S. Army veteran who served as Mississippi state field secretary for the NAACP. Baldwin deeply admired Evers and later wrote, “When he died, something entered into me which I cannot describe, but it was then that I resolved that nothing under heaven would prevent me from getting this play done.” “Blues for Mister Charlie” opened at the Actors Studio in New York in April of the following year, 1964.

The play opens with the murder of Richard, a young Black boy in a small Southern town, which closely resembles Till’s murder. There is no suspense: Lyle Britten, the white owner of the local general store, has shot Richard and dumped his body outside of town. The grieving family includes Rev. Meridian Henry, Richard’s father and the nonviolent leader of the local Black church; Meridian’s mother (and Richard’s grandmother), Mother Henry; and Juanita, a young Black student who loved Richard. Parnell James, the white liberal editor of a local newspaper, tries to appease all parties, unsuccessfully.

aug_22_blues_for_mister_charlie.png

Each character in “Blues for Mister Charlie” is forced to think about where they stand, what they see, and who matters. For instance, Meridian confronts Parnell for being complicit with Lyle in the systems of white violence and white legal impunity. Meridian says,

I watched you all [Parnell and Lyle] all this week up at the Police Chief’s office with me ... And for both of you—I watched this, I never watched it before—it was just a Black boy that was dead, and that was a problem. He saw the problem one way, you saw it another way. But it wasn’t a man that was dead, not my son—you held yourselves away from that!

Lyle thinks that Richard’s death is a legal problem and aims to escape punishment for his crime. Parnell thinks Richard’s death is a social problem and tries to hold together the Black and white members of the community to avoid further violence. Meridian insists that Richard is a person, not a problem. His response is intimate and visceral: “My son!”

Baldwin’s fictional characters often reckon with their place in the world. Meridian, Lyle, and Parnell each calculate their history, position, and status in a society that unequally distributes life and death, health and wealth, beauty and grace. Baldwin turns this reckoning on his readers, too. “People who shut their eyes to reality simply invite their own destruction,” he wrote.

Baldwin is asking us this question: In a world of white violence and Black death, what do you see?

Near the end of Act II in “Blues for Mister Charlie,” Parnell arrives at the church to find Juanita, a young Black student grieving Richard’s death. Parnell realizes, belatedly, that Juanita and Richard were in love:

Parnell: You loved him.

Juanita: Yes.

Parnell: I didn’t know.

Juanita: Ah, you’re so lucky, Parnell. I know you didn’t know. Tell me, where do you live, Parnell?

How can you not know all the things you do not know?

Parnell: Why are you hitting out at me? I never thought

you cared that much about me. But—oh, Juanita! There are so many things I’ve never been able to say!

Juanita: There are so many things you’ve never been able to hear.

Juanita describes Parnell’s ignorance with biting irony: “Ah, you’re so lucky, Parnell.” Her words question his integrity and announce judgment on his unknowing.

Parnell fails to understand his place in the community because he has not engaged openly and vulnerably with the people around him. This is why Juanita’s question is so damning in its simplicity: “Tell me, where do you live, Parnell?” she asks. If you cannot be here, she seems to be saying, you cannot be anywhere.

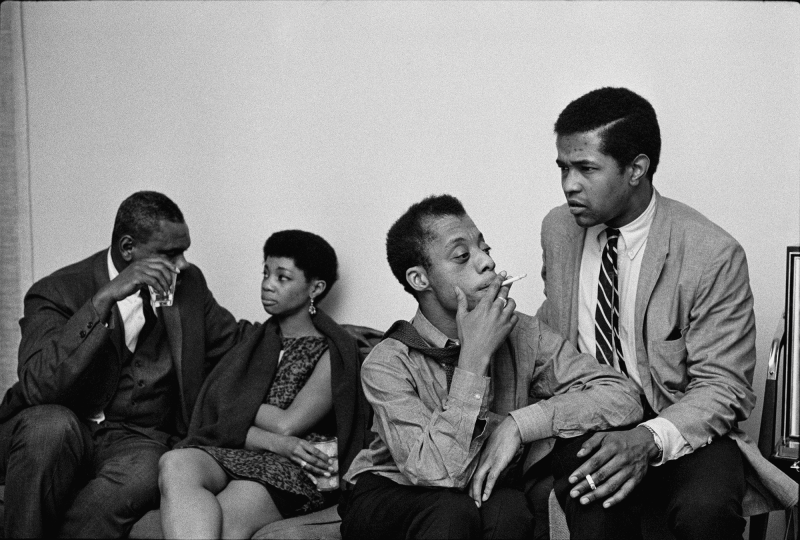

aug_22_culture_baldwin_party.png

Baldwin links integrity of the body and integrity of the heart in this scene. He suggests that we cannot understand the world around us without fully embracing our senses: seeing, hearing, touching, and feeling the bodies of the people who are most threatened by violence and cruelty. But senses are not sufficient. Parnell sees Juanita, speaks with her, and touches her, but he holds something back. His integrity fails not because his body lacks function but because his heart lacks courage.

Baldwin is calling us to be present to ourselves and the world around us. He is asking what we know, how we know it, and whether we have the courage to confront the answers.

Juanita’s question for Parnell becomes Baldwin’s question for us:

Tell me, where do you live?

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!