Oct 19, 2021

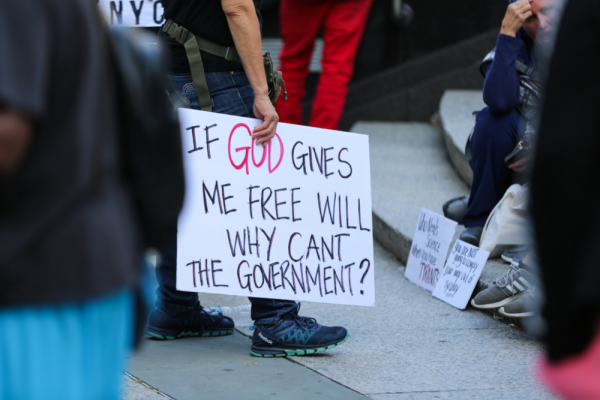

The FDA’s full approval in late August of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, known commercially as Comirnaty, has led to a spate of government and corporate vaccine mandates for employees and patrons — as well as the inevitable backlash. Much of that backlash has been on religious grounds, with some Christians claiming exemption from the mandates using what journalist Mattathias Schwartz describes as the “rhetorical Swiss Army knife” of religious freedom.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login