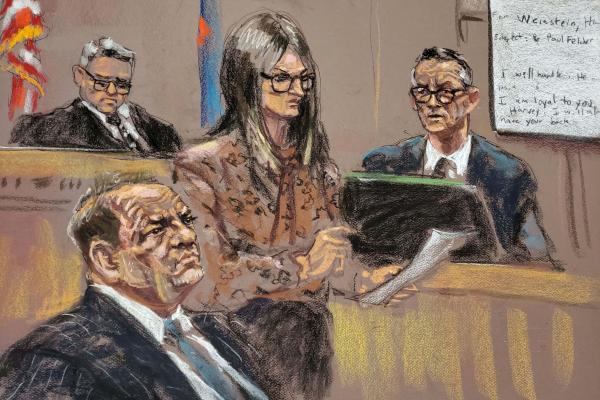

On Friday, Megan Twohey, one of the journalists who broke the story about Harvey Weinstein’s alleged abuse, released an interview she conducted with Donna Rotunno, Weinstein’s criminal defense attorney. As the interview came to a close, Twohey asked Rotunno if she had ever been sexually assaulted. Rotunno said she hadn't, and after an awkward three seconds passed she added, “Because I would never put myself in that position.”

Minutes later — and after a baffling back and forth — Twohey asked Weinstein’s attorney if the “burden of safety” should lie with the victim of abuse or the abuser. Rotunno’s response? “I think it should rest equally.”

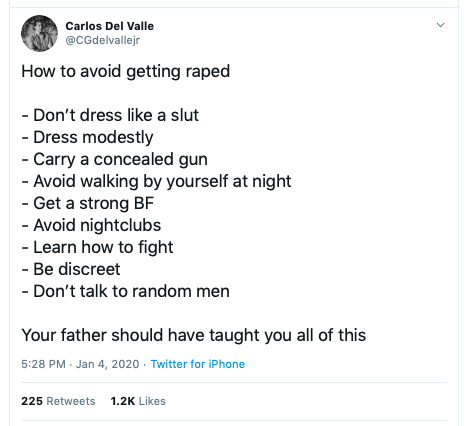

Rotunno’s comments — which may give insight into how she will defend Weinstein — certainly exhibit a not-uncommon view: that victims of sexual abuse are somehow responsible for the abuse they suffer. “She had it coming.” “Look at what she’s wearing. She’s asking for it.” “She shouldn’t have been drinking.” Or even, “I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet ... And when you’re a star, they let you do it ..."

A few months ago one Twitter user even offered a crash-course for women on “How to avoid getting raped”:

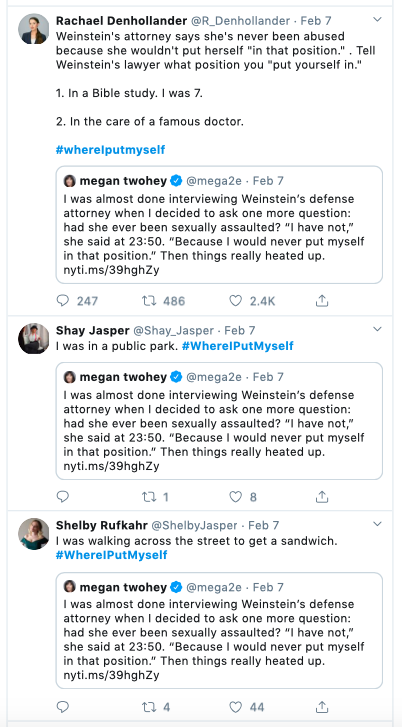

In response to Rotunno’s comments, former gymnast Rachael Denhollander, who helped bring justice to the hundreds of victims of Larry Nassar, shared where she was when she was abused:

“1. In a Bible study. I was 7.

2. In the care of a famous doctor.”

Denhollander asked others to share as well, using the hashtag #WhereIPutMyself. Responses poured in: “simply being a toddler in my own home,” “twelve at a movie,” “asleep in my sleeping bag,” “in the pastor’s car,” “a family wedding reception,” and on, and on, and on. In less than a week, over 1,500 people have tweeted using this hashtag.

If it wasn’t already true on the face of it, Denhollander’s comments and the responses to her reveal that the “burden of safety” does not lie with the victim, and a victim certainly doesn’t share blame for putting themselves “in that situation.” Denhollander’s comments and her connection with survivors on social media model two important ways for Christians to engage this conversation.

First, the Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes speaks to the importance of empathy. “Again, I observed all the oppression that takes place under the sun. I saw the tears of the oppressed, with no one to comfort them. The oppressors have great power, and their victims are helpless” (Ecclesiastes 4:1 NLT). Notably, Ecclesiastes strikes a mournful tone. This simple recognition of injustice and powerlessness is a good and right way to cast our lot on the side of victims of abuse.

Second, the Old Testament prophets moved past the sorrowful recognition we find in Ecclesiastes, and they raised their voices in opposition to injustice. In a culture (not unlike our own) that valued power and commoditized people, the prophets of Israel and Judah called God’s people to care for the least among them: the poor, the orphan, the widow, and the immigrant. They often suffered significant social consequences for this, and their writings reveal tortured souls who longed for justice and righteousness on earth.

Denhollander and other advocates like her show modern-day Christians how we can mirror the empathy and advocacy of the Old Testament writers. Simply put, we listen to those around us. As we listen to stories of abuse and its effects, we must allow ourselves to feel some of the agony and powerlessness of another. “Inviting someone into your life,” an abuse survivor recently told me, “can be the difference between literal life and death for that person.”

Denhollander is doing much more than observing the tears of the oppressed, though. She is elevating the voices of survivors, her own among them. Rather than allow the Weinsteins to continue to control the narrative — and thus the power, as philosopher Michel Foucault taught us— Denhollander is holding up a mirror that reflects the darkest parts of our culture and urging us to stare ourselves in the face. This type of vocal advocacy will likely come at a cost, just as it did for the prophets of old who stood on the side of the weak.

These are the questions Christians must ask ourselves during this time of reckoning with the sexual abuse crisis: Will we listen to and join Denhollander and others in seeking justice and righteousness? Will we prop up a culture that places the blame on women who “had it coming”? Or will we hear the cries of the oppressed and stand with them? Will we honor power, or will we follow the upside-down way of Jesus, who said it would be better to sleep with the fishes than to “cause one of these little ones to stumble”?

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!