Silicon Valley

I WAS SITTING in a large auditorium full of market researchers. A speaker suggested that, by selling wrinkle cream, we were helping to make the world a better place because women would feel better about themselves. I looked around the room, thinking, “Is everyone buying into this? Do people really think this is true, or do they see that it’s just a corporate pep talk?”

I had worked in the world of international market research for nearly 10 years. Though there were a few moments like this one when something just didn’t feel right, in many ways I still didn’t see the issues I see so clearly now — marketing techniques are the air we breathe.

I eventually left my work in marketing to pursue a master’s in social justice and a doctorate in theological ethics. I began to investigate how marketing practices negatively impact how we live as human beings and how we think about marketing in the church. In contemporary society, we tend to view marketing techniques as neutral tools that can be applied in different contexts — whether for businesses, nonprofit fundraising, or church communication. But can we adapt tools that have been developed in the context of capitalistic profit maximization to the mission of the church? Are there fundamental differences in how the church views and relates to human beings?

I had worked in the world of international market research for nearly 10 years. Though there were a few moments like this one when something just didn’t feel right, in many ways I still didn’t see the issues I see so clearly now—marketing techniques are the air we breathe.

LIKE THE FRENCH police officer in Casablanca who was “shocked, shocked” to find gambling in Rick’s Cafe, in the wake of the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol, social media companies were “shocked” to discover violent anti-Semitic and white nationalist agitators lurking in plain sight on their platforms. With their usual earnest hypocrisy, the companies took action, banning tens of thousands of groups and individuals from the social media universe. Facebook and YouTube suspended Donald Trump’s accounts. Twitter permanently banned him.

Never mind that in the preceding days and weeks those same social media platforms hosted the planning for Jan. 6, or that for years they have profited from a business model that ignores truth and promotes outrage. But when some of their more unruly customers got off the leash and started threatening the people who write antitrust laws, Facebook, Google, and Twitter suddenly became tribunes of civility.

Of course, such monumental hypocrisy from Big Tech gave many Republican politicians the opportunity to change the subject from their own possible complicity in the insurrection to what they claim is suppression of free speech by the liberals in Silicon Valley. To this, clever liberals have replied that the First Amendment only applies to government, not to private corporations.

The Last Black Man in San Francisco is a film of operatic intensity, poetic emotion, political clarity, and a touch of magic realism.

THE AGE OF THE ROBOTS is here. If you didn’t notice, it’s because we’re calling them artificial intelligence (AI) and they don’t look like we expected. They’re the touchscreen kiosk that has replaced the cashier at Panera, the mechanical arms and claws flipping burgers at fast food joints, the drone that may someday deliver your Amazon order. They’re the software that can turn a baseball box score or corporate earnings report into a wire service news story.

According to a recent report from the Brookings Institute, about 38 percent of the adult population could be put out of work by smart machines in the next generation. The choices we are making about our AI future depend upon our answer to the question Wendell Berry posed 30 years ago with his book What Are People For? Up to now, at least in the U.S., the answer has been that people exist to generate corporate profits.

Andrew Yang, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur running for the Democratic presidential nomination, argues that Donald Trump is president because automation eliminated 4 million manufacturing jobs in the Rust Belt states Trump narrowly won. Yang expects that blue collar alienation will multiply soon, when driverless vehicles replace 3.5 million truck drivers.

"WE LIVE AS if the connections provided by digital technologies are vital,” writes Gaymon Bennett in the cover story, “and indeed we have made them so.”

Guilty as charged. Hang around the Sojourners office long enough and you’ll hear stories about how we used to keep a list of our subscribers in a shoebox and write articles on typewriters. But those days are done: Today our office hosts a congregation of laptops, tablets, screens, cameras, and smartphones that we need to access databases, send messages, and update our website. When a network upgrade happens to knock out the Wi-Fi, we all go home because, well, how could we work?

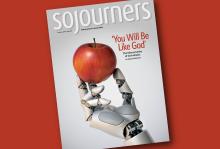

In this issue, we take a careful look at the twisted logic—and theology—that brought us Facebook, iPhones, 2-day shipping, Alexa, and 1,700,000,000 search results in .48 seconds: “Innovation is always good, and more is always better. Create powerful technologies, improve humanity and the planet, and make piles of money. This is the secularized spirituality of Big Tech at work, buffering it against any ability to contemplate its own potential evil,” writes Gaymon Bennett.

Religion writers get a lot of curious mail in their inbox. Our favorite this week was from Instapray, a social praying app.

Instapray does exactly what you'd think it would — matches communal prayer with the real-time get-it-anywhere nature of social media by allowing users to add, share, comment on, and update prayers. Like similar apps before it, there’s a spiritual motivation, too — users can mark that a prayer has been answered, or “repray” with others in solidarity of situation or spirit.

Most social prayer apps to date are some variation on Instapray, if less catchy/hokey in name — the Prayer Network, Ora, Intercede, Fellowshipper. Their thesis is clear — we often forget or don’t make time to pray; we don’t know who and what to pray for; we want to know our deep questions or petitions are being heard. (One also has to wonder whether the psychological pitfalls of digital social tools apply doubly when faith is involved — “What about all my prayers left publically unanswered? Why doesn’t anyone else share my prayer?".)

There’s a growing sense of partnership potential between Silicon Valley and faith communities, but the market for Christian social media to date remains largely untapped. It seems developers and faith leaders have yet to discover their collaborative sweet spot, where often-private religious inquiry best meets digital social tools. Instapray is one newer attempt at finding that nexus — success TBD.

In the meantime, here are 5 other Christian apps tooled to provide a closer walk with … well, each other.

“THE COMPUTER’S not the thing. It’s the thing that will get us to the thing,” intones Joe MacMillan (Lee Pace), the enigmatic visionary at the heart of AMC’s new techno-drama Halt and Catch Fire. Set in the early 1980s in Texas’ “Silicon Prairie,” the series chronicles a small, fictional software company that enters the personal computing fray. This is the age of IBM dominance and the improbability of an underdog company taking down the computer Goliath is the premise of the show.

HCF is a kind of origin myth: a drama that tries to capture the spirit and personalities that drove the personal computing revolution that reshaped the world we now inhabit. Across the cable universe, HBO offers another riff on the same theme set in the present day. Silicon Valley is a satirical send-up of startup culture and the boy-men who rule the northern California empire to which we are all in thrall. In tone and style it is the antithesis of the self-consciously serious HCF. But the two shows share a similar preoccupation with exploring the humans who make technology even more than the technology itself.

This is partially a necessity of good storytelling. Nothing slows down a story like having to explain technical expertise. At best you can get a few gags out of the science geek spewing unintelligible jargon to the bewildered “everyperson” (think Sheldon’s whole persona on The Big Bang Theory). But this narrative limitation also hints at the enigma both shows are trying to explore: Who are the people who understand the jargon and create the technology that defines our new digital age? What is the nature of this kind of power?

“Bubble living” might be delusional, but it expresses deep and serious yearnings.

Take “Champagne music” maker Lawrence Welk. His music variety show on ABC was built on perpetuating the squareness of a prewar world being challenged by postwar change.

My father was still watching Welk reruns 40 years after it ceased production in 1971. They reminded him of a world long supplanted.

My first career: print journalism. Current status of that field: on life support.

My second career: pastoring neighborhood churches. Current status of that field: on life support.

My third career: writing and publishing books. Current status of that field: on life support.

My fourth career: implementing client-server data management systems. Current status of that field: on life support.

Do you see a trend here? I did. So now I try to stay nimble and to keep moving. My publishing business is entirely electronic. I have cycled through three websites and three subscription systems in 10 months. I do more of my church consulting online.

I got fitted for a custom-tailored suit this week.

Not because I suddenly found a pot of money. I didn’t, and I didn’t need to. The cost for this Hong Kong tailor is comparable to what I have been paying for off-the-rack suits.

My problem is middle age. My shifting body type makes off-the-rack suits too wide in the shoulders and too long. It’s proof that life keeps on changing, and that the way forward must include getting unstuck from old ideas.

In a world far removed from the tragic cesspool of Washington scheming and maneuvering, real people flocked to Central Park on El Camino Real for this town’s first Bacon & Brew Festival.

It was wildly successful. Vendors ran out of food and beverages; sponsors closed off ticket sales early. The parched and mean-spirited landscape that ideologues are trying to manufacture seemed distant.

As they stood in line for burgers, barbecue, fries smothered in cheese, and microbrewed beers, young adults eyed each other’s pregnant bulges and baby strollers. I heard no muttering about Obamacare. People have better things to do than to defund a program that benefits fellow citizens.

Forget Wall Street. Today's "best and brightest" are heading to California's Silicon Valley and New York's Silicon Alley, and to a few other tech-startup hot spots.

Thousands of aspiring engineers, web developers, designers and marketers live in dormitories, work in open-floor bullpens, attend coding competitions to enhance their skills, and work hours that defy body chemistry. It sounds like fun.

Some work on projects that make a positive contribution to society; some are coding games, entertainment apps, and schemes to monetize friendships.

They take stock for pay and wait for the magic letters "IPO" to appear. Meanwhile, their employers fight for their loyalty with free food and party-on office cultures.

The brass ring they chase looks like Marissa Mayer, the 37-year-old former Google star who was tapped to lead Yahoo out of its extended doldrums. Like any public person, Mayer is painted in stark colors: as both immensely talented and merely lucky, an inspiring leader and a rude monster, likely to succeed and sure to fail.