john the baptist

IN FALL 2014, the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra performed Brahms’ Requiem on a Saturday evening two months after the murder of Michael Brown Jr., at a concert hall about 10 miles from Canfield Green, where Brown was killed and his adolescent body left out in the Missouri August sun for four and a half hours.

That summer and fall, people in the city and county of St. Louis lived in the tension of waiting — we were waiting for a grand jury to make a decision. Not a verdict about the officer’s guilt: The grand jury was tasked with deciding whether this murder was even a murder at all — whether anything happened on Aug. 9 that could even be considered maybe a crime. Maybe worth investigating. Or whether it was just a regular day’s work.

As intermission was ending and folks were back in their seats, just as the orchestra was regathered and the conductor was raising his baton, a small group of ticketholders in the audience stood up and sang. In singing, they asked the audience, made up largely of people who could choose whether or not they were impacted by the grand jury’s decision that loomed over the city like the shadow of death, to make a decision of their own. They stood up, one by one, and joined their voices in an old labor song: “Which side are you on, friend, which side are you on?” they sang. “Justice for Mike Brown is justice for us all. Which side are you on, friend, which side are you on?” They hung banners made of bedsheets over the balcony; one that echoed the piece being performed that evening was painted: “Requiem for Mike Brown, 1996-2014.”

These protesters brought this question — this disruption — into a space that could’ve kept it to business as usual. They sang the two refrains in repetition, almost like a Taizé chant, for several minutes, then they left the hall together, chanting a chant that at the time was still brand-new to most Americans: Black Lives Matter.

The disrupters left to a mix of silence and applause from the audience and the musicians. The concert continued, but the question hung in the air. It’s the same question that hangs in the air of many of Jesus’ disciple-calling stories, and it’s certainly the question that pervades Matthew’s telling of Jesus’ good news.

APRIL 2019. On the second day of our 65-kilometer walk on the Jesus Trail in Galilee, I began feeling dizzy and faint. Berry, my hiking partner, told me to drink more water. That helped, and we were able to make our way from Nazareth to our next stop in Cana, site of a wedding Jesus attended.

But the Jesus Trail continued, often on narrow stony paths speckled with animal droppings, up and down hillsides, across streams of springtime water where thistles grew over our heads, through meadows of waist-high grasses, and finally up and over Mount Arbel leading down to the Sea of Galilee. Our destination was Capernaum, site of Jesus’ headquarters during his ministry.

Exhausted at the end of our hike and with blistered feet, I turned to Mark’s gospel. Already in 1:21, Jesus “went to Capernaum”; the next morning he “went to a deserted place to pray” (verse 35). Then he “went throughout Galilee, proclaiming the message” (verse 39). I will never read the words, “Jesus went” the same way again. Not by horse, carriage, automobile, train, or plane. Not communicating by telegram, radio, phone, email, YouTube, or Zoom. Just trudging by dusty, sandaled feet, bereft of Nikes!

‘Lords of the world’

SINCE THAT HIKE, I have been pondering the Incarnation. Was it necessary for the Infinite One to go that far down? To be born a lower-class, brown-skinned, black-haired Middle Eastern Jew whose only means of transport was by scratched and calloused feet? To live under an enemy occupation determined to keep its subjects poor and politically powerless?

GOD IS NOT a neutral observer of our worldly affairs. “God takes sides,” the Brazilian theologians Clodovis and Leonardo Boff explain in Introducing Liberation Theology. God is not a dispassionate consultant, nonpartisan mediator of divisions, or a disinterested negotiator of political antagonisms. “God takes sides and comes on the scene as one who favors the poor,” Mexican theologian Elsa Tamez writes in Bible of the Oppressed. “The God of the biblical tradition is not uninvolved or neutral,” U.S. theologian James H. Cone argues in A Black Theology of Liberation. “God is active in human history, taking sides with the oppressed.”

God has already decided to live in solidarity with people who have survived injustice after injustice. The incarnation reveals the partisanship of God—that, in Jesus, God becomes one of the “disinherited,” to use Howard Thurman’s language. The life of Jesus is the story of how God takes the side of “people who stand with their backs against the wall,” as Thurman puts it in Jesus and the Disinherited, populations “disinherited from participation in meaningful social process,” groups segregated from “any stake in the social order.”

The Bible passages this month call us to examine where we stand. They illumine the borders of power—the divide between privilege and oppression that slices through our communities—and prod us with a question: Which side are you on?

Waiting for the "baptizer to appear in the wasteland."

I WAS CALLED “John the Baptist” because of that great revival movement we had down by the Jordan River. We were all so hopeful then, especially after my cousin Jesus showed up. I suspected he was The One to save our people, even after he asked me to baptize him. But when I heard that heavenly voice announcing, “This is my Son,” I knew. Judgment was coming! Jesus would know how to separate the wheat from the chaff and burn the chaff with unquenchable fire (Matthew 3:11-17)!

I was on a roll. We Jews would live by Yahweh’s law, Rome’s yoke would be cast off, and everything would change. I kept preaching and baptizing, and I even chastised Herod Antipas for his unlawful marriage (Mark 6:17-18), confident he was part of the “chaff.” Jesus was our Messiah, the Anointed One of Israel—and I had been his forerunner (Matthew 3:2-3). Yet here I am—chained to a wall in Herod’s dreary prison cell. What went wrong?

I assumed Jesus would gather and train disciples to prepare for a revolution. But rumors from my own disciples tell me this is not happening. He’s sending them out on missions to Jews, but not as I expected. They don’t even carry a backpack or a staff. Their only weapon is against physical diseases. And their promised rewards are arrests, floggings, and trials (Matthew 10:1-25). This sounds like a parody of what I was hoping for! Jesus acts more like a teacher and healer—even a prophet—but not like a king, not like an anointed Messiah!

In the midst of so much death, how can we Christians celebrate Easter?

These questions can be paired with questions regarding our own sense of worship on that day. How much have we Christians replaced justice with worship, not taking one into serious relation with the other? Are we accustomed to worship in the total absence of justice?

Dec. 4 was a beautiful reminder, in the long struggle for justice, that, no matter how long we wait, God hears our cry. And love and justice will win.

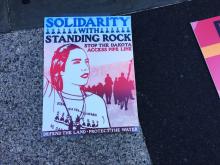

A few weeks ago, Chief Arvol Looking Horse issued an invitation to clergy and faith leaders to stand in solidarity with the people of Standing Rock. He said he was hoping maybe 100 would respond. But I joined thousands, in a procession of faith leaders, to gather around the sacred fire at the Oceti Sakowin Camp at Standing Rock.

I knew something special was happening here.

Perhaps here is where we need John the Baptist most. He might turn to us and call us to ordinary acts of grace. He might call us to give what we have. He might call us to stay at our jobs and do them well. He might call us to the radical idea that seemingly ordinary lives can be imbued with the extraordinary spirit of God to transform the world.

During this Christmas season, we expect to enjoy times of family and conviviality and joy. Such expectations have been shattered this year. We could throw our hands up in despair. We could lament over a shattered world. We could grieve those we have lost, the dreams that have been shattered. We could pray fervently for courage and hope. We could worship together and so resist the encroachments of death upon our lives. We could protest and march and demand change. We could call our representatives and demand action.

We should do all these things.

And as we do all these things, we should also live ordinary lives infused by the extraordinary call to love God and love neighbor.

John the Baptist is an irritant in the midst of Advent.

In the Gospel reading for this week in Luke 3:7-18, he is in the wilderness excoriating the crowds who came seeking baptism and repentance and deliverance.

“Who warned you…?,” John wants to know. Who told you to come out here? What did you think you would find? Who the crowds find is a fiery prophet of God, preaching judgment upon the injustice that permeates this world.

Every Christmas, my family makes an 8-hour drive to celebrate the holidays with extended family. This year, to fight off sleep half-way through the trek, my sister started reading aloud in the book of Luke. Before you begin to feel remorse about your worldly choices in travel entertainment this past holiday, you should know that we opted for this reading only after finding a disappointing selection at Red Box. While Hollywood failed us, God did not. The Spirit revealed something new in a story I’ve heard over and over.

My sister read aloud. Chapter 1: Zechariah, Mary, Elizabeth, babies on the way. Chapter 2: Jesus, prophesies. Chapter 3: John the Baptist, and wait, what?

Luke 3:7-14 reads:

When the crowds came to John for baptism, he said, “You brood of snakes! Who warned you to flee God’s coming wrath? Prove by the way you live that you have repented of your sins and turned to God. ... The crowds asked, “What should we do?” John replied, “If you have two shirts, give one to the poor. If you have food, share it with those who are hungry.” Even corrupt tax collectors came to be baptized and asked, “Teacher, what should we do?” He replied, “Collect no more taxes than the government requires.” “What should we do?” asked some soldiers. John replied, “Don’t extort money or make false accusations. And be content with your pay.”

When Harper was born we decorated the nursery in a Noah’s Ark theme…images of Noah and of animals entering a large wooden boat two-by-two. It’s a common enough decorating scheme for kids' rooms.

I mention it because this week at Bible study we discussed how weird it is that the beheading of John the Baptists isn’t a common decorating scheme for kid’s rooms.

Because this is just too gruesome a tale to show up on rolls of juvenile wall paper.

In case you missed the details, here’s what happened:

So Herod is the ruler of the region, and while vacationing in Rome he gets the hots for his brother’s wife who he then marries. John the Baptist, then suggests that maybe that’s not ok.

Now, Herod likes John, as much as anybody can like a crazy bug-eating prophet who lives outdoors and speaks consistently inconvenient truths. Truths such as it’s not ok to marry your brother’s wife, which, incidentally, is the truth that when spoken, got him arrested to begin with.

It also got John on the bad side of Herod’s new illegal wife Heroditas. She did not like John. Then when Herod throws himself a big birthday party his daughter-in-law Salome dances for him and all the other half-drunk generals and CEOs and celebrities who were there.

We don’t know the exact nature of her dance but we do know that it “pleased” Herod enough that he offered to give her anything she wanted up to half of his kingdom. So, you know, I don’t think it was the Chicken dance.

The Christianized Jesus -- the turning of a radical into a conservative shadow of his former self -- explains our problem of establishing and celebrating freedom fighters today. It is important that our progressive heroes be given their deserved fame, an accurately reported fame, and this is crucial in ways that impact our own activism.

Jesus of Nazareth was not a Peak Performance Strategist as the prosperity preachers would have it. Nor was he a foreigner-hating patriot as the tea party would argue. Obviously American politicians and their lobbyists pursue so many policies that are against the teachings of Jesus but are supported by mainstream Christian opinion. In fact, Jesus' parables and sayings push the spiritual revolution of gift economies, and of justice through radical forgiveness.

"And all ate and were filled; and they took up what was left over of the broken pieces, twelve baskets full. And those who ate were about five thousand men, besides women and children." --Matthew 14:13-21

Immediately before the story of the feeding of the 5,000 is a description of a very different sort of meal: John the Baptizer's head on a platter. And just as women and children are included among the multitude fed on the beach (a detail unique to Matthew's version of the story), the female sex is also represented in the account of John's demise: Herodias, sister-in-law of Herod, asks for the head of the Baptist; her nameless daughter, with no detectable squeamishness, delivers the request to the king and serves up the plated head to her mother. (That women in all of their moral complexity are present throughout Matthew's gospel - recall also the women who appear in the genealogy of Jesus in chapter one -- is an observation worthy of closer scrutiny. See, for instance, Jane Kopas's 1990 essay in Theology Today).