good

I don’t know about you, and the people you know, but most people I know who call themselves Christians are particularly proud of the certainty that they are ‘good enough’.

It’s an odd phrase when you think about it; in a world simmering with chaos, injustice and upheaval, oppression, poverty and human trafficking, in our cities filled with addiction and unrest, our prisons cramped and over-flowing, do any of us really believe that the best we can do is ‘good enough’?

Can many of us actually congratulate ourselves, or our faith communities for our impact on our neighborhoods, schools or cities?

From white villages Easter bells resound.

Rejoice! Give thanks! I raise my voice

Evil disappears from the world.

And that means somewhere God must be.

What makes one a good person? Additionally, what makes one a good Christian? I have been spending some time wondering about this as news of Mandela’s death has been making it’s way across the planet. Was he a good man? I think so, but how do we measure that? How do we know? And if, as some have claimed, his greatness stemmed from his willing embodiment of his Christian faith, I need to know if he was a good Christian.

Guy Sorman writes of Mandela:

“The Commission for Truth and Reconciliation, founded by President Mandela and led by Bishop Tutu, is perhaps the most concrete example of Mandela’s Christian faith. Instead of the vengeance and reprisals that were expected and feared after years of interracial violence, the commission focused on confession and forgiveness. Most of those who admitted misdeeds and even crimes — whether committed in the name of or in opposition to apartheid — received amnesty. Many returned to civil life, exonerated by their admission of guilt.”

Mandela is exemplary not because he was perfect, always kind to everyone he met, an ideal husband and father, but because of these larger virtues that he also attempted to live out. He lived into these virtues — all of them, large and small, and all of them incompletely.

TODAY THE Middle East—where about 60 percent of the population is under the age of 25—is a region dominated by humiliation and anger. Failure plus rage plus the folly of youth equals an incendiary mix.

The roots of anti-American hostilities in the Middle East run deep. We can start with the fact that what we consider our oil lies beneath their sands. Couple that with U.S. support of repressive regimes, the presence of foreign troops on their land and in their holy places, and the endless wars waged there, ultimately fueled by the geopolitics of energy. Add to that the unresolved Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which continues to drive the deepest emotions of mutual frustration, fear, and retaliation throughout the Middle East and around the world.

Injustices and violence caused by the oil economy have sparked a reaction from dangerous religious fundamentalists in the Muslim world. Fundamentalism—in all our faith traditions—is volatile and hard to contain once it has been unleashed, and it is hard to reverse its essentially reactive and predictably downward cycle.

Three principles may help us navigate a path out of this mess. First, religious extremism will not be defeated by a primarily military response. Ample evidence proves that such a strategy often makes things worse. Religious and political zealots prefer military responses to the threats created by Islamic extremism. Ironically, this holds true on both sides of the conflict; the fundamentalist zealots also prefer the simplistic military approach because they are often able to use it effectively. Fundamentalists actually flourish and win the most new recruits amid overly aggressive military campaigns against them.

I recently went back to the Lincoln Memorial to tell the story of how and why I wrote my new book, On God’s Side: What Religion Forgets and Politics Hasn’t Learned About Serving the Common Good. And I reflected on my favorite Lincoln quote, displayed on the book’s cover:

“My concern is not whether God is on our side: my greatest concern is to be on God’s side.”

I invite you to watch this short video, and to engage in the discussion as we move forward toward our common good. Blessings.

Whenever I hear the term Common Good I think of Thomas Paine’s infamous pamphlet Common Sense,which challenged the British government and the royal monarchy, but did not challenge the institution of slavery. As an African-American woman I enter the Common Good conversation cautiously because I know that in our society we have a habit of taking what is good for Western hegemony and making it the standard for everyone else.

As we pursue the Common Good, let us remember what was once considered common and good during earlier points in American history: chattel slavery, indigenous genocide, and institutionalized sexism. To truly come to a Common Good, we need to honor a diversity of voices and challenge our assumptions about what is common and what is good. Our default is to take what is good for our culture, gender, or community and make it the common standard for all. I have experienced being invited into organizations that were aiming to do good in the world, but an expectation existed that I would be silent about my unique concerns as an African woman. I know that denying my reality can never be good for my spiritual, physical, or social well being.

“Oh, God!”

That cry has echoed ever since news of the horrific shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn.

As the names of those who died are made known, that cry is followed by a question: Why? Why does God allow evil?

This agonizing question arises among religious believers after tragedies great and small. It’s also one that priests, pastors, rabbis, and imams will wrestle with.

The Rev. Jerry Smith of St. Bartholomew Episcopal Church in Nashville said that although this weekend marked the third Sunday in Advent, which focuses on hope in advance of Christmas, the church also has to talk about the reality of evil.

“We have to speak about this shooting and we have to recognize, this is the very darkness that Christ came into the world to dispel,” Smith told The Tennessean.

The Rev. Neill S. Morgan, pastor of Covenant Presbyterian Church in Sherman, Texas, says on the congregation’s website that now is a time for prayer.

But, says Morgan, “all the existential questions about God, justice, and love” will come. “We wonder what we can do to prevent such violence in the world, our nation, and our community.”

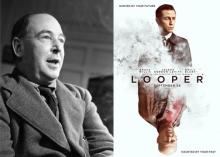

As the credits rolled after Looper in a packed Chinatown movie theater in Washington, D.C., I simply sat in reverent silence. Moviegoers on all sides began to rise and quietly leave the theater, but for a brief moment all I could do was just sit there. Quite simply, the movie blew my mind.

When I snapped out of it my thoughts started racing, analyzing the ending, which I won’t ruin for you, and the movie as a whole. It wasn’t a question of whether it was “good” or captivating — those were givens. Rather, I started mining the film’s rich themes and questions, particularly what it said about love.

While sitting there, lost in my mind, I began to notice the music accompanying the names moving onscreen. The song’s chorus sang something like, “I loved you so much that it’s wrong.”

I don’t think the song choice was an accident.

That lyric, I think, illuminates the crux of the film: can something like “Love” — not just romantic love — become perverted? Or, in other words, can our love for one person lead us to do horrible things to others?